How Congress Funds Tyranny and Government Inflates Its Role w U.S. Congressman Chip Roy | Ep. 332/28/2023 In today's episode of the "Let People Prosper" podcast, I have the honor of being joined by U.S. Congressman Chip Roy (R-TX) who shares his insights on:

Congressman Chip Roy’s bio (here):

0 Comments

In 2021, a bipartisan coalition ended school property tax abatements for corporations and renewable energy companies. On this week’s Liberty Cafe, Vance Ginn and Tim Hardin join me to discuss how Big Government Texas Republicans are attempting to restore this program for their friends in Big Business.

Both Republicans and Democrats at the national level have put us down a path of slow growth, massive deficits, and high inflation. With a new Republican majority in the U.S. House and the daunting debt ceiling fight over the bloated $31.4 trillion national debt almost exclusively due to excessive spending, there’s a proven pro-growth, pro-liberty path.

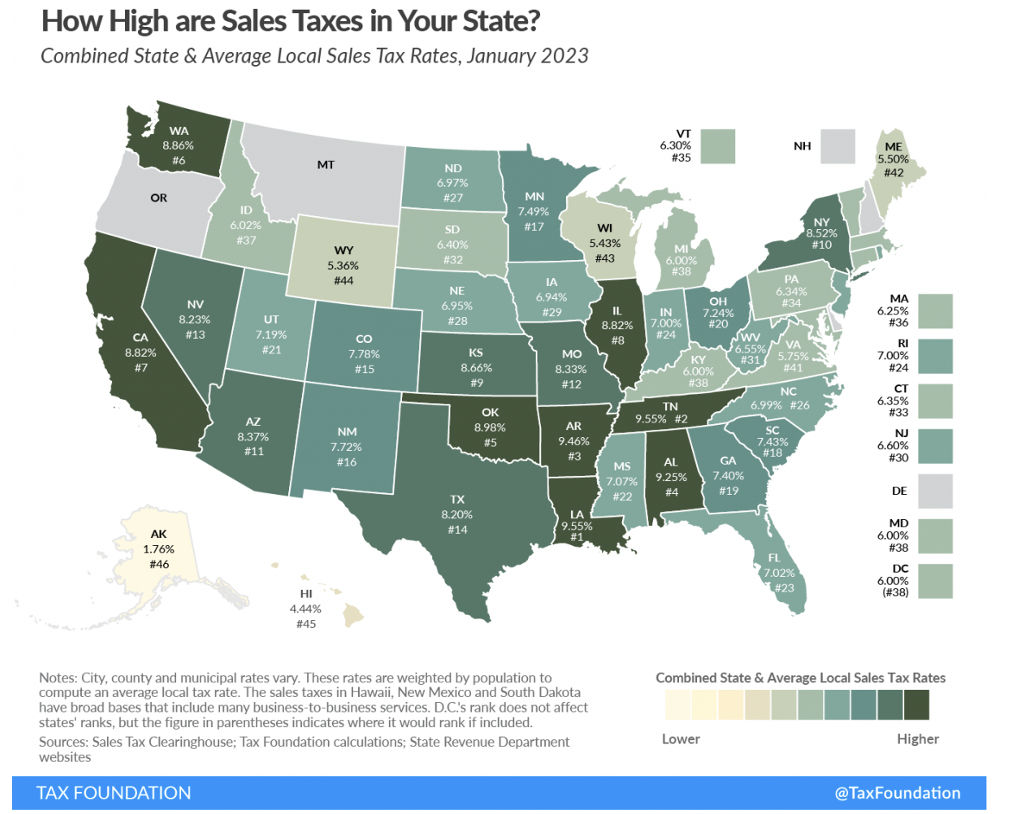

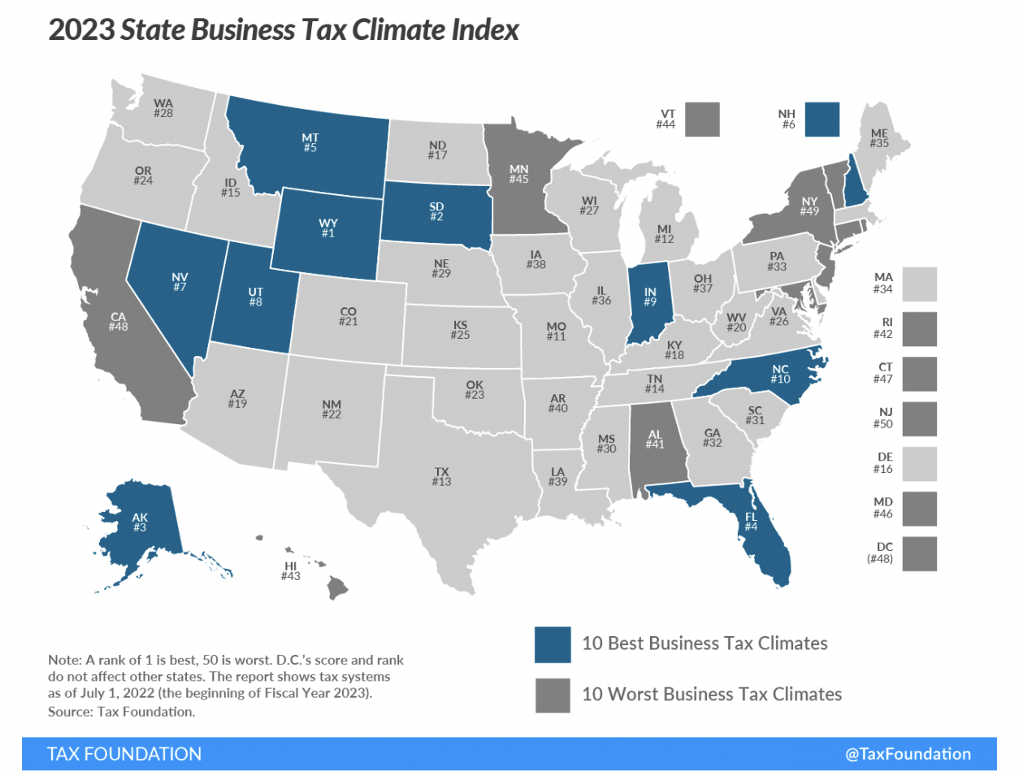

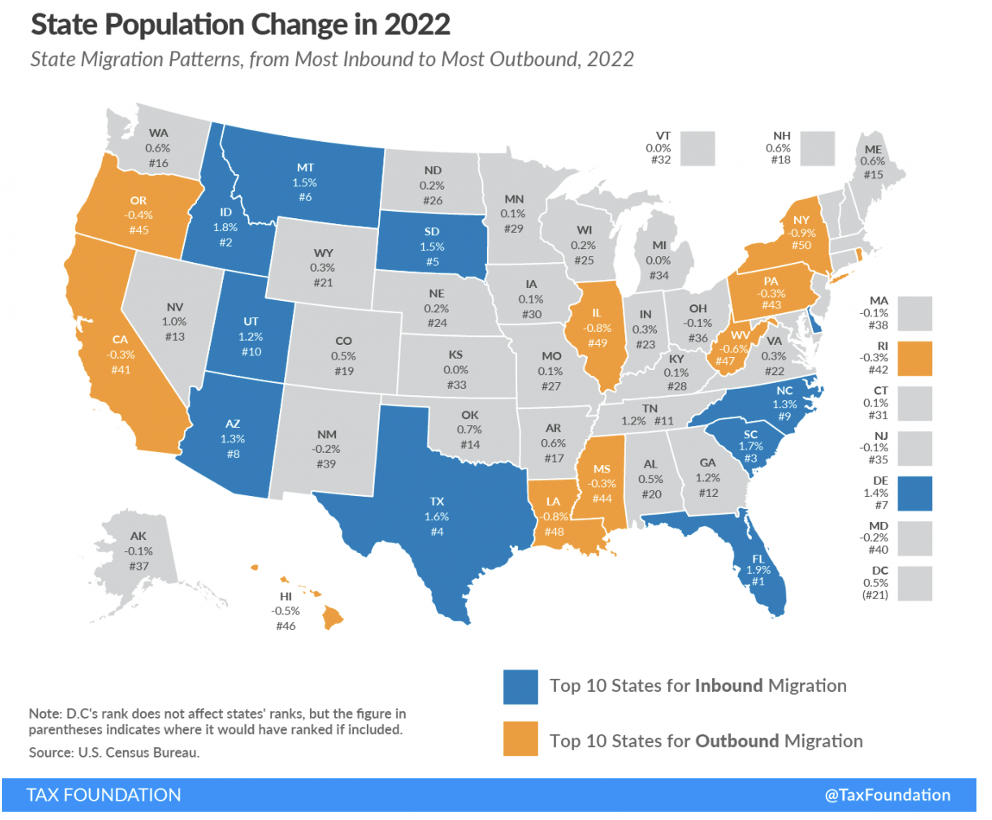

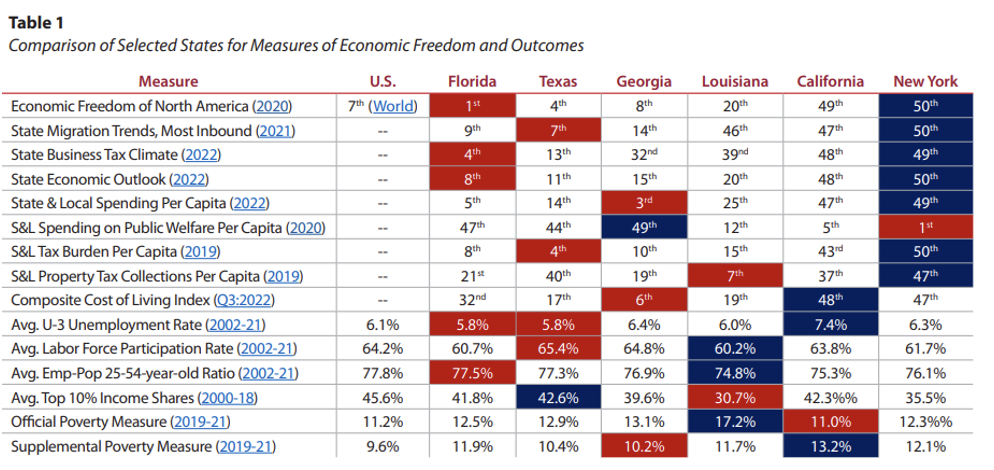

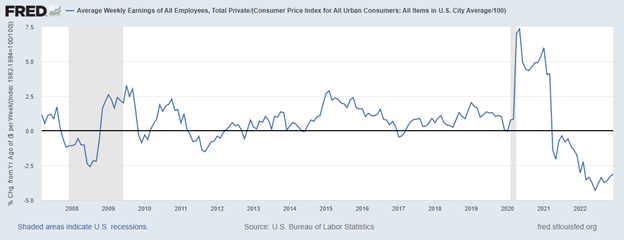

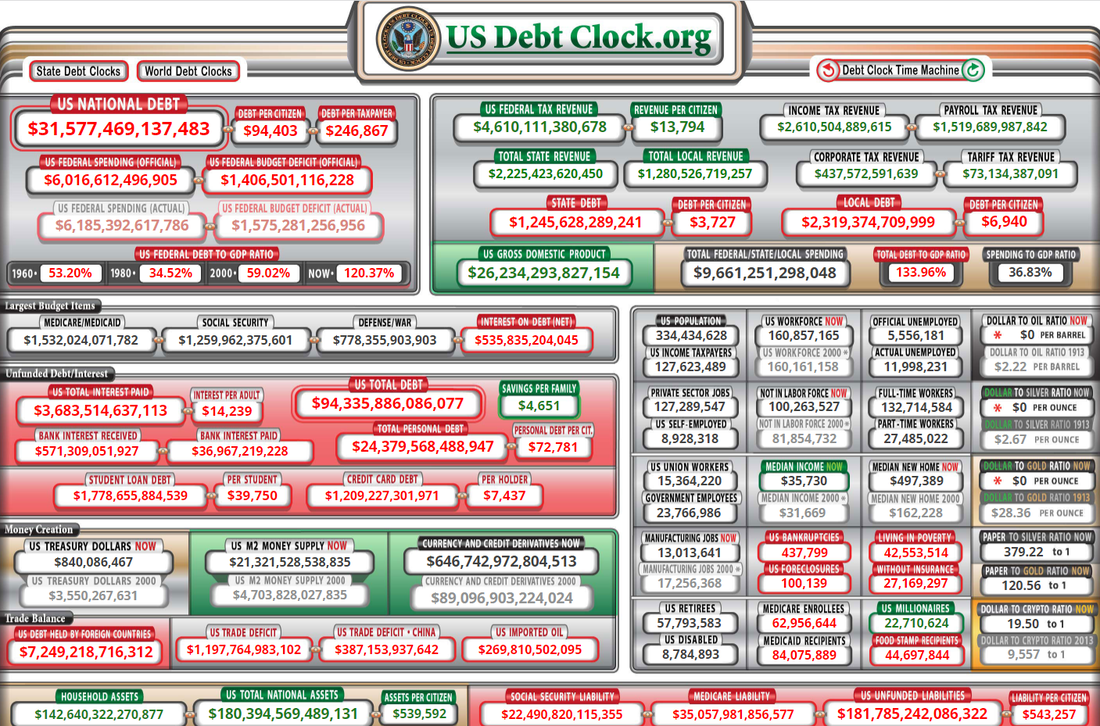

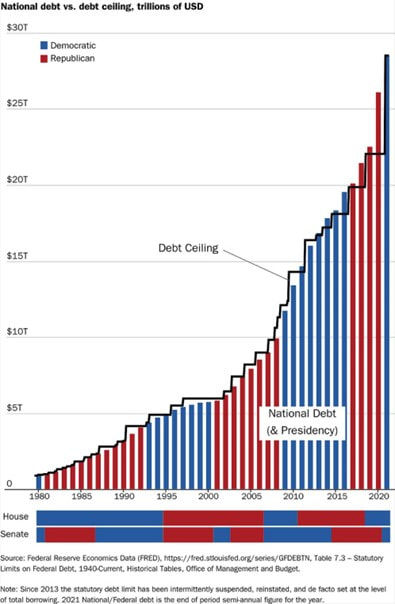

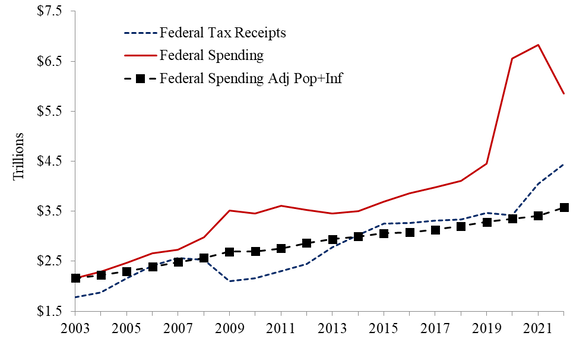

In 2022, the U.S. had real GDP growth of just 0.9 percent (Q4-over-Q4), the highest inflation in 40 years, the highest mortgage rates in 20 years, and the worst stock market in 14 years. Average real weekly earnings have now declined year-over-year for 22 straight months. Fortunately, history is a good guide for how to overcome this mess. The two of us have served as chief economists at the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), though 50 years apart. One of us (Arthur Laffer, originator of the “Laffer Curve”) was the first chief economist of the OMB in the Nixon White House. The other (Vance Ginn) was the last associate director for economic policy at the OMB in the Trump White House. While much has changed since the OMB was formed in 1970, the problems are basically the same today. There remains a lot of unjustifiable government spending, prosperity-killing taxes, unwarranted regulations, excessive liquidity, and harmful interference in international trade. But just because counterproductive economic policies have been around for a long time doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try for a better world. Each of the above areas is the subject of intense debate. In politics, these debates have their short-term winners and losers as judged by elections. But the principles of economics aren’t determined by votes. The remedy for economic malaise has been and is less government, not more. Free-market, pro-growth policies are the cure. The legacy of the 1970s is now called the era of stagflation, and the 2020s are shaping up to be known for the same, or worse. Even with 50 years of experience, many people still haven’t learned a lesson. During the Nixon and Ford administrations, the economy was stifled at every turn. The dollar was taken off gold and devalued, resulting in higher inflation. Then there was the imposition of wage and price controls, which did nothing to stop inflation but instead ravaged the economy. Government spending was out of control. Taxes were raised, and tariffs imposed, including a 10 percent import tax surcharge; such was the wisdom of the D.C. crowd. The consequences were rising inflation, stock market collapse, impeachment, and a weak economy. Then, President Jimmy Carter tried to do more of the same with the same consequences. There followed a true renaissance, led by President Ronald Reagan’s tax and regulatory cuts and Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker’s sound monetary policy. Inflation crashed, the stock market soared, new jobs surged, and Reagan won re-election in a landslide, winning 49 states. And then there was the sad interlude of George H.W. Bush, who broke his promise by raising taxes, leading to a one-term presidency. President Bill Clinton, partnering as he did with House Speaker Newt Gingrich, cut government spending by 3 percentage points of GDP, cut capital gains tax rates while exempting owner-occupied homes from this tax altogether, and finally, he and the Republicans pushed the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) through Congress. On the bad side, he raised the top two tax rates. But the spending restraint contributed to a budget surplus for four straight years. President George W. Bush, with a penchant for spending more and for temporary tax cuts, was followed by President Barack Obama, with a desire on steroids to spend even more, plus he nationalized health care. Stagnation took hold, and prosperity faded. In his first two years, President Trump reversed some of the prior 16 years of bad policy with substantial tax cuts, historic deregulation, and other measures that helped get government out of the way, contributing to the lowest poverty rate and the highest real median household income on record. But with the onset of the pandemic, prosperity was cut short by the ill-advised massive spending increases and lockdowns. Today, we’re once again mired in a sea of bad policies and bad consequences despite President Joe Biden’s self-serving narrative. With tax hikes, massive spending, oppressive energy regulations, soaring debt levels, trade protectionism, and a bloated Fed balance sheet, stagflation was given a brand-new lease on life. We should follow the proven, pro-growth path (not currently taken) of sound money, minimal regulations, free trade, flat taxes, and most of all, spending restraint for the sake of the economy and human flourishing. It’s also great politics. With this elixir in hand, it would be springtime again in America. And that is something Americans can believe in. Vance Ginn, Ph.D., is an economist and senior fellow at Young Americans for Liberty and previously served as the associate director for economic policy of the White House’s Office of Management and Budget from 2019 to 2020. Arthur Laffer, Ph.D., is an economist from Nashville, Tennessee, and was the first chief economist of the White House’s Office of Management and Budget. Originally published at The Federalist. Recent data from the Tax Foundation reveals that Louisiana has the highest average combined state and local sales tax rate of all the states. The bulk of this burden comes from its local taxes, the second highest in the nation. Pair these findings with Louisiana’s progressive income taxes of a graduated personal income tax rate of up to 4.25% and a corporate income tax rate max of 7.50%, and there’s no wonder why the Pelican State has a net out-migration problem. According to the Tax Foundation’s business tax climate index, the state ranks 12th worst in the country. Personal income taxes disincentivize work, and sales taxes can lead consumers to shop elsewhere and businesses to relocate. Employers and consumers want to be where they can keep more of what they earn, which helps explain why Florida, a state with no personal income taxes and a combined sales and local tax rate that’s more than 2.5-percentage points lower than Louisiana’s, had the highest net in-migration last year. Clearly, Louisiana’s tax code needs an overhaul if the growth and flourishing of Louisianans are priorities. But so does the state’s spending. To start, the Pelican State could consider joining the 14 states in the flat-income tax revolution. As more states flatten or remove their personal income taxes, Louisiana’s costly progressive income taxes will become much less appealing. Moving to flat personal and corporate income taxes would be a pro-growth step forward toward the eventual greater goal of eliminating these costly taxes, helping to compete with places like Florida and Texas, both of which don’t have personal income or corporate income taxes. Considering that the ultimate burden of government is how much it spends, reforming the tax code is just one piece of the puzzle. The excessive government spending at the state and local levels, compared with reasonable metrics like the rate of population growth plus inflation which helps measure the average taxpayer’s ability to pay for government spending, burdens Louisianans. Furthermore, Louisiana’s state and local debt is estimated to be about $7,600 per person owed by 2027, plus another nearly $28,000 per person owed in unfunded liabilities over time, so there are clearly massive barriers in the way for Louisianans to flourish. This is an issue because heavy spending leads to heavy burdens on state residents and decreased economic freedom, which Louisiana can’t afford to lose more of, considering how far it falls behind other states. Not surprisingly, Georgia, Florida, and Texas all boast lower spending than Louisiana, with improved economic freedom and poverty rates. Meanwhile, Louisiana has the highest official poverty rate in the country. The rankings for the Pelican State aren’t quite as bad as the highly progressive states of New York and California, which are hemorrhaging population to other states. Incentives matter, so people are voting with their feet to flee high cost, low freedom states.

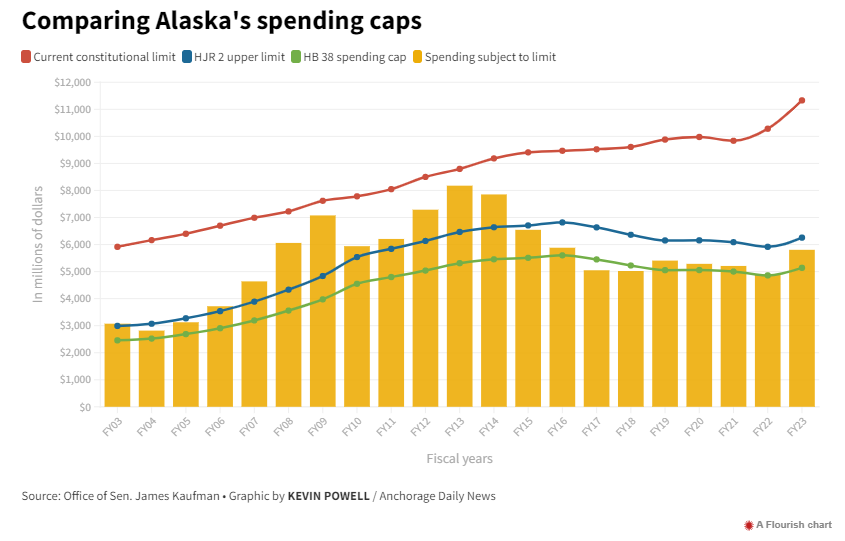

Louisiana should start its comeback story by adopting a stronger spending limit, similar to the one recently passed in Texas. Spending caps help governments stay limited, which is imperative for states to thrive as it forces them to narrow their scope. In turn, the private sector has more elbow room to grow and people have greater ability to prosper. This would also help provide more surplus funds to put toward cutting, flattening, and eventually eliminating personal and corporate income taxes. Louisiana has too great of a culture and too much potential for it to be squandered by burdensome spending and taxes. It’s time for serious spending restraint and major tax reforms to provide the best path forward. Originally published at Pelican Institute. News: Lawmakers say a new fiscal cap could stabilize Alaska’s economy. It could also tank it.2/25/2023 A tighter limit on state spending is a top priority for Republicans in the state House of Representatives this year, but a proposal to tie spending to gross domestic product is raising questions about whether a tighter limit will hamstring the state’s ability to fund critical services and weather future economic downturns. Alaska already has a spending cap, enacted in 1982, based on the state’s population and inflation. But lawmakers have called it “the perfect law,” because it is so difficult -- essentially impossible -- to break. The state simply does not spend nearly as much as that limit allows for. Now, House Republicans are indicating they favor a pair of bills that would force lawmakers to tighten the belt on the state budget even as they are considering hefty spending increases to shore up ailing services. The House Judiciary committee could advance the measures as early as Monday. Proponents of a tighter spending cap say it will help prevent the boom-and-bust cycles that have dominated Alaska’s oil-based economy for decades. Gone will be the days, they say, when years of high oil prices are accompanied with fat budgets, and oil price crashes put the state in austerity. A spending cap will reign in the appropriators when the revenue fortunes are good, the argument goes, leaving money for years when revenue shrinks. A new limit on state spending was part of a proposed framework for a new fiscal plan put forward by a bipartisan working group in 2021 which also listed new revenue sources and a new Permanent Fund dividend formula in its final report. Lawmakers from both parties agree that a new spending cap should be part of a fiscal plan, but they disagree on the order of business. Some think resolving the Permanent Fund dividend calculation should take precedence. Others say that new revenue streams for the state are most important. House Republicans, who dominate the chamber’s majority caucus this year, have cited a tighter spending cap as the first item they’d like to tackle. The odds are stacked against the policy in a divided Legislature. And according to some policy analysts, that’s a good thing. Spending caps, opponents say, leave states with unwieldy budgets that cannot respond adequately to the state’s changing needs. Still, proponents are charging ahead. Chief among them is Sen. James Kaufman. An Anchorage Republican and retired oil and gas quality manager, he devised a new idea in 2021 to limit Alaska’s spending to a percentage of the state’s gross domestic product, excluding the public sector. GDP measures the value of the goods and services produced in-state. While more than 20 states have some form of spending cap, none have tied their budgets to gross domestic product, a complex figure calculated by federal financial institutions. In 2021, Alaska’s GDP was $57.3 billion, the smallest of all states except Wyoming’s and Vermont’s — two states with smaller populations than Alaska’s. Kaufman says that the metric, rather than the more commonly used consumer price index or personal income, “is an accurate measurement of the state’s economic performance.” Excluding the public sector, which has accounted for roughly 20% of Alaska’s GDP in recent years according to data from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, puts the focus on Alaska’s private sector, dominated by resource development. “Sometimes we have an embarrassment of riches where we have a lot of revenue come in, and the next year it can be radically different,” said Kaufman in an interview. “To try and break the boom-and-bust cycle, I started considering caps that would help that, and which caps would be the most helpful.” Tying the state’s spending to the private sector “ensures that government does not outgrow the private sector that it is meant to support” and that the state avoids becoming overly dependent on revenue from the Permanent Fund, according to a statement accompanying the bill. Kaufman’s policy would be based on an average of the preceding five years’ GDP. He is proposing a statutory limit set at 11.5% of that average, while a companion constitutional amendment would set the upper limit at 14%. That way, lawmakers could agree to exceed the 11.5% limit with a two-thirds majority, but would not be able to exceed the 14% ceiling. Under the proposal, both the statutory limit and the constitutional limit would have to pass to be effective. It’s a tall order — constitutional amendments must be adopted by a two-thirds vote by both chambers of the Legislature. It’s a tall order also for the state’s economy — of the last 20 budgets, all but three would have exceeded the proposed statutory limit. Half would have exceeded the proposed constitutional limit. Over the course of two decades, such a spending cap would have prevented the state from spending $5 billion, roughly the equivalent of an entire year’s budget.

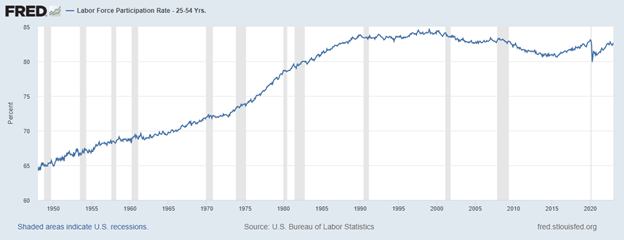

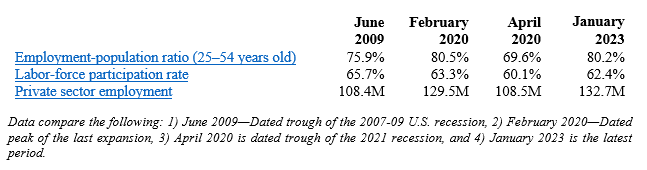

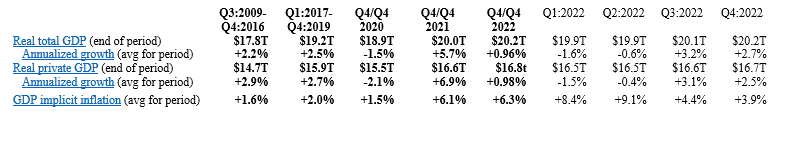

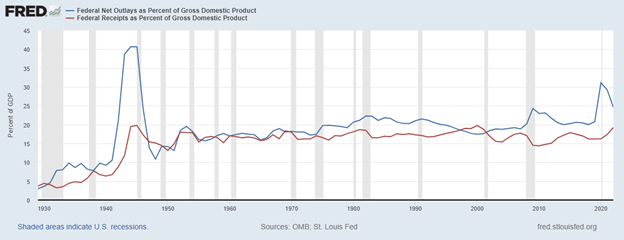

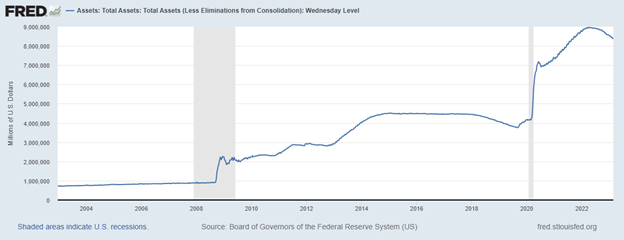

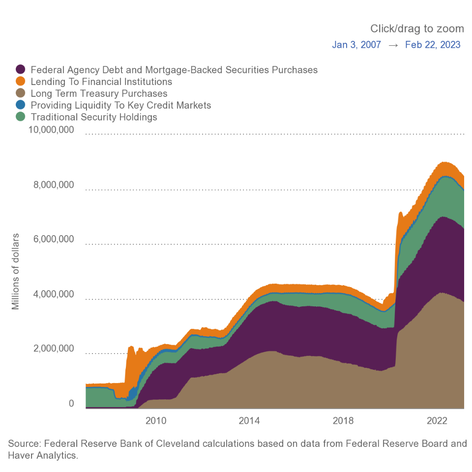

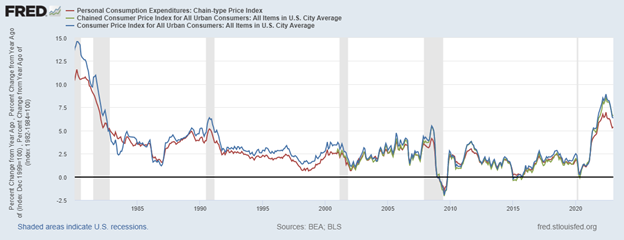

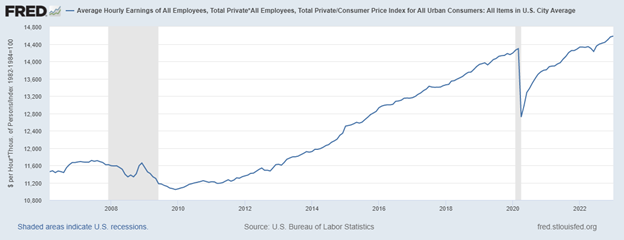

Gov. Mike Dunleavy’s proposed spending plan for the coming fiscal year would exceed the proposed statutory limit, but remain below the proposed constitutional limit. Dunleavy has favored a tighter cap on state spending and has proposed legislation to that effect during his first term in office, but he has yet to put forward such a bill this year. Dunleavy spokesman Jeff Turner did not respond when asked if the governor intends to advocate for his own plan or for Kaufman’s. Instead, Turner said in an email that the governor’s office “does not comment on bills until they have passed the Legislature” because they can be substantially changed before that, and that “Dunleavy has always advocated for a plan to limit the growth of the state budget.” Kaufman’s proposal has many exceptions: the limit would not apply to the Permanent Fund dividend, disaster relief or federal dollars, among other exceptions. But it would apply to all general fund spending on capital projects and operating expenses, which covers building and road maintenance, schools, public safety, and other programs that have seen effective cuts in recent years. Kaufman said he settled on the 11.5% limit for the statutory proposal to match the exact level of spending in the 2022 fiscal year budget, which was shaped by low oil prices and lingering pandemic-era federal funding. Even amid these complexities, Kaufman calls it “kitchen table economics.” ‘Everybody would be worse off’ Comparing a state budget to household expenses is part of the problem, according to Bernie Gallagher, a policy analyst with the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Gallagher said spending caps are inherently arbitrary and pinned to a particular moment in time. Just as Alaska’s previous spending cap proved too generous, a new spending cap could prove too onerous. “It makes it very difficult to override that limitation when the capped amount is inadequate to meet the needs of state families or communities,” said Gallagher. Kaufman’s efforts to design a more resilient limit to reign in Alaska’s fluctuating economy could prove to be insufficient, because GDP “is just as volatile as personal income,” Gallagher said. “In fact, it has a slower rebound effect than personal income,” he added. “Many other states and conservative groups that do advocate for spending limits don’t use state GDP for that reason — because it’s just capturing too much.” University of Alaska Anchorage economist Kevin Berry raised similar concerns about gross domestic product, saying it is a flawed mechanism for capping state spending, because it could exacerbate longer economic downturns, just like the one the state is currently facing. In Alaska, where the oil industry makes up a large part of the private sector, a long-term downturn in oil prices could bring down the state’s GDP even if the population and its needs remain unchanged. The bigger issue, Berry said, is that tying state spending to the GDP could prevent the state from responding to recessions with increased spending, as governments often do. “What happens when the government ramps up spending, is it helps support households and support businesses and make the recession less bad,” said Berry, citing unemployment insurance as an example. “That money supports household incomes and that also leads to more revenue for businesses and prevents businesses from suffering and people going out of business. We stop the whole negative cycle that way.” Tying spending to GDP, he said, would mean that during prolonged economic recessions, “at the same time the private sector would be struggling, the public sector would have to struggle too, so everybody would be worse off.” Berry said that would be exacerbated by the fact that Alaska’s economy is what he called “counter-cyclical,” meaning it tends to do better when the Lower 48 economy is doing worse. Federal fiscal policy, in turn, is designed to meet the needs in the Lower 48, and sometimes works against Alaska’s interests. “That means that federal policy is doing the opposite of what we want it to do in any given period, potentially, exacerbating our business cycle,” Berry said. During a recession, economic principles dictate that the state government might need to spend more money “to counter the cycle and smooth things out. But if you’ve got a spending cap that’s tied to GDP, we can’t do that.” The bill makes an effort to overcome the potential problem by tying spending to a five-year average, rather than a single year. That isn’t necessarily enough, Berry said. “The problem is, we’ve had a prolonged downturn. It’s very likely in the future at some point, we’ll have another prolonged downturn, and then we can get stuck in this trap,” he said. ‘Different things to different people’ Kaufman is a member of the Senate’s bipartisan majority, which has named improving the state’s long-term fiscal outlook as one of its priorities. But at a press conference, leaders of the caucus shrugged off Kaufman’s proposal. “A long-term fiscal plan means different things to different people,” said Sen. Donny Olson, a Golovin Democrat who co-chairs the finance committee. Discussing a spending cap “highlights the fact that if you’re going to deal with a long-term fiscal plan, you’ve got to figure in where your new revenues are going to be coming from.” Some Senate members appear interested in handling other elements of the state’s fiscal plan before they reconsider the spending cap. “Before we can really, really focus on a long-term fiscal plan, we need to figure out the Permanent Fund dividend issue. That’s what we really need to do first,” said Sen. Elvi Gray-Jackson, an Anchorage Democrat. Other senators said that a cap on spending from Alaska’s Permanent Fund revenue already in practice limits the money at the state’s disposal, thus limiting state spending. In 2018, lawmakers passed a law capping the amount that can be withdrawn from the earnings of the Permanent Fund based on the performance of the fund’s investments — or percent of market value (POMV) — to ensure that the Legislature does not overspend and deplete it over time. “The revenue cap — the POMV law — actually provides us with a spending cap today, because it limits the revenue as long as we hold the line on that law. We still have to figure out where we spend the money but it means there’s a cap in place,” said Sen. Matt Claman, an Anchorage Democrat who chairs the Senate Judiciary committee, which is assigned to handle Kaufman’s proposal. The proposed policy has seen more support from conservative House members who sit on the House Judiciary Committee, which is scheduled to take action on both the statutory limit and the constitutional limit on Monday. They could vote to advance the bill as is, amend it, or table it for further consideration. If the judiciary committee approves the measure, it still must pass scrutiny in the Ways and Means Committee, then the Finance Committee, before reaching the House floor. “It’s very challenging for private enterprise to make long term decisions when there’s so much instability in policy, especially spending at the state level,” said Rep. Will Stapp, a freshman Republican from Fairbanks who is the primary sponsor for the measure in the House. “I like the fact that we are creating a link between state spending and Alaska’s private sector.” If anything, Stapp said, his conservative colleagues wonder if the percentage limits proposed in the bill should be set even lower. The new spending cap has backing from the right-wing Alaska Policy Forum. Vance Ginn, a Texas-based economist and fellow with the forum, told the House Judiciary committee that the measure would incentivize private sector economic growth while limiting the public sector. But Ginn appeared unfamiliar with the particulars of Alaska’s economy, including its reliance on the oil industry for revenue and the lack of broad taxes like an income tax. Another prominent advocate for a tighter spending cap is the Alaska Chamber of Commerce, which has for several years listed the cap as the business group’s top priority. Kati Capozzi, chamber president, said that the group’s advocacy for a new spending limit came in response to the crash in oil prices that occurred a decade ago, leading to what she called “the yoyo budget cycle,” and a perpetual fear among business owners that new taxes are on the way. “The business community is constantly under pressure and frankly threatened that there’s going to be a tax increase every time we are unable to pay our bills. This would provide some security for the business community,” said Capozzi. A spending cap is the “most important thing that needs to be addressed” in the state’s long-term fiscal plan, according to Capozzi, because it would provide “side rails” that would attract more investment in Alaska, by signaling to investors that a crash in oil prices would not lead to “a knee jerk reaction to go get more revenue from the business community.” But Rep. Cliff Groh, an Anchorage Democrat who sits on the House Judiciary committee, wonders if limiting the state’s spending could hamper the business community in the long run. “Given that corporate executives and people in charge of companies stress how much a highly qualified workforce is so important for setting up, for expanding or bringing their companies at all to a state — if the schools become crummy, the roads become crummy, and the public services are at such a low level it’s unattractive to employees — you can imagine that that can occur, that a certain improperly designed spending limit could lead to a smaller population and a smaller economy,” said Groh at a recent House Judiciary committee hearing on the measure. Ginn responded that a review of spending caps in other states indicated that such limits force states to “really prioritize those dollars — wherever they should go — within that spending limit.” “We need to have the least burdensome form of taxation on individuals … And a good big way to do that is to ensure that spending doesn’t go out of control so that we don’t need as many taxes,” said Ginn. “Additional spending doesn’t necessarily equal better outcomes.” ‘A red herring’Berry, the Alaska economist, said that while the GDP could be a flawed foundation for a spending cap, that doesn’t necessarily mean the idea of a stricter spending limit is bad. “This is not to say that I’m for a spending cap or against a spending cap. I think that’s a policy choice the state needs to make. I think there’s just better ways to do it,” Berry said. An alternative to the new mechanism would be adapting the existing spending limit to match existing revenue levels. Lawmakers are not currently considering such a proposal. “The general idea of tying the size of government service to the demand for those services makes a lot of sense. So tying it to CPI (consumer price index) and tying it to population,” Berry said, referring to the 1982 limit. “Maybe we did set it too high, but it doesn’t require complex mechanisms to bring it down.” Still, some economists argue that binding spending caps that tie the hands of lawmakers are never a good idea. Gallagher, with the Center on Budget and Policy Proposals, said that experience in other states has shown that spending limits “do little or nothing to make government run any more efficiently or ensure that tax dollars are well spent. It shifts costs from states to cities and towns, which only moves the burden over to property taxes and fees.” Gallagher said a better solution to Alaska’s spending volatility could be a progressive tax, like an income tax, that is more dependable year-after-year and ensures the burden of paying for state services does not fall disproportionately on a single group. Gallagher called that “a much more sustainable model” than Alaska’s current dependence on revenue sources that can fluctuate wildly. “It’s a state that has massive, massive revenue volatility. Addressing that is really being lost. Addressing the spending side is actually a red herring. The real focus should be over on — are we collecting a sufficient amount for the needs of our state?” Gallagher said. Yet more than a month into the legislative session, state lawmakers are not considering any new broad taxes. Dunleavy, a conservative Republican, has proposed shoring up state revenue by monetizing carbon through keeping trees standing and injecting carbon into the ground, in an effort to meet state needs without imposing new taxes on businesses or individuals. But skeptics say that even if that plan pans out, revenue is still years away and will hardly be enough to make up for falling oil returns in the future. As lawmakers have debated the spending cap proposal, they have largely sidestepped questions on what would be required to meet a lower limit. Amid falling oil prices, state budgets over the past decades have translated to cuts to virtually every state service. And Alaskans are beginning to notice; private and public sector leaders have reported it is increasingly difficult to stem the tide of out-migration because state services like education, public safety and transportation infrastructure are not meeting expectations. “One of the things that people don’t mention is a spending cap that’s binding, that requires cuts, requires identifying those cuts. So the question is, what are people talking about cutting?” Berry said. Originally published at Anchorage Daily News. Key Point: The U.S. economy in 2022 had the slowest Q4-over-Q4 growth during a recovery since at least 2009 and average weekly earnings are now down for 22 straight months as inflation keeps roaring. But there’s hope if we just give free-market capitalism a chance to let people prosper. Overview: Although President Biden recently tried to claim that the state of the union is strong, facts tell a different story. The government failures that drove the “shutdown recession,” high inflation, and weak economic growth over the last three years continue to plague Americans. This includes excessive federal spending leading to massive deficit spending adding up to $7 trillion since January 2020 to reach nearly $31.5 trillion in national debt—about $250,000 owed per taxpayer. This has created a fight between the Biden administration and House Republicans over the debt ceiling, as raising it must come with spending restraint to avoid some of the fiscal insanity that will lead to insolvency if nothing is changed. And more inflation could be on the horizon if the Federal Reserve chooses to monetize more more of the new debt, which past excess has already contributed to 40-year-high inflation rates. These government failures with little relief from pro-growth policies in sight mean that things will get worse before they get better. Labor Market: The Bureau of Labor Statistic recently released its U.S. jobs report for January 2022. This report came with substantial revisions to seasonal adjustments and population estimates which could bias the data for a while given that the revised estimates include the much of the last three years of data that are highly volatile. And recall the recent report by the Philadelphia Fed finds that if you add up the jobs added in states in Q2:2022 there were just 10,500 net new jobs rather than more than 1 million reported. The establishment survey shows there were +517,000 (+3.3%) net nonfarm jobs added in January to 155.1 million employees, with +443,000 (+3.6%) added in the private sector and +74,000 (+1.4%) jobs added in the government sector. Most of the private sector jobs were added in the sectors of leisure and hospitality (+128,000), private education and health services (+105,000), and professional and business services (+82,000), which these three sectors led over the last 12 months as well; information (-5,000) and utilities (-700) were the only net job declines over the last month and no sector had net job losses over the last year. Average hourly earnings for all employees was up by 10 cents last month to $33.03, or up by +4.4% over the last year. And average weekly earnings in the private sector increased by $13.35 last month to $1,146, or up by +4.7% over the 12 months. The household survey had another large increase of +894,000 jobs added to 160.1 million employed There have been declines in net jobs in four of the last 10 months for a total increase of +1.8 million since March 2022, which is about half of the +3.6 million of the net jobs added per the establishment survey. The official U3 unemployment rate declined slightly to 3.4% which is the lowest since 1969. But challenges remains as inflation-adjusted average weekly earnings were down -1.5% over the last year for the 22nd straight month, weighing on Americans budgets to make ends meet. And since February 2020 before the shutdown recession, the prime age (25-54 years old) employment-population ratio was 0.3-percentage point lower, prime-age labor force participation rate was 0.3-percentage point lower, and the total labor-force participation rate was 0.9-percentage-point lower with millions of people out of the labor force thereby holding the U3 unemployment rate much lower than otherwise. Economic Growth: The U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis’ recently released the 2nd estimate for economic output for Q4:2022. The following table provides data over time for real total gross domestic product (GDP), measured in chained 2012 dollars, and real private GDP, which excludes government consumption expenditures and gross investment. And most of the estimates for Q4:2022 and growth in 2022 were revised lower, providing more evidence that 2022 was a very weak year if not a recession. The shutdown recession in 2020 had GDP contract at historic annualized rates because of individual responses and government-imposed shutdowns related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Economic activity has had booms and busts thereafter because of inappropriately imposed government COVID-related restrictions in response to the pandemic and poor fiscal policies that severely hurt people’s ability to exchange and work. Since 2021, the growth in nominal total GDP, measured in current dollars, was dominated by inflation, which distorts economic activity. The GDP implicit price deflator was +6.1% for Q4-over-Q4 2021, representing half of the +12.2% increase in nominal total GDP. This inflation measure was +9.1% in Q2:2022—the highest since Q1:1981—for a +8.5% increase in nominal total GDP that quarter. This made two consecutive declines in real total (and private) GDP, providing a criterion to date recessions every time since at least 1950. In Q3:2022, nominal total GDP was +7.6% and GDP inflation was +4.4% for the +3.2% increase in real total GDP. But if inflation had been as high as it was in the prior two quarters or had the contribution of net exports of goods and services (driven by natural gas exports to Europe) not been 2.9%, real total GDP would have either declined or been essentially flat for a third straight quarter. In Q4:2022, there was a similar story of weakness as nominal total GDP was +6.6% and GDP inflation was +3.9% for the +2.7% increase in real total GDP. But if you consider the +2.7% real total GDP growth was driven by contributions of volatile inventories (+1.5pp), government spending (+0.6pp), and next exports (+0.5pp) which total +2.6pp, the actual growth is quite tepid like it was in Q3:2022. For all of 2022, real total GDP growth is reported +2.1% year-over-year but measured by Q4-over-Q4 the growth rate was only +0.9%, which was the slowest Q4-over-Q4 growth for a year since 2009 (last part of Great Recession). The Atlanta Fed’s early GDPNow projection on February 24, 2023 for real total GDP growth in Q1:2023 was +2.7% based on the latest data available. The table above also shows the last expansion from June 2009 to February 2020. A reason for slower real private GDP growth in the latter period is due to higher deficit-spending, contributing to crowding-out of the productive private sector. Congress’ excessive spending thereafter led to a massive increase in the national debt by more than +$7 trillion that would have led to higher market interest rates. This is yet another example of how there is always an excessive government spending problem as noted in the following figure with federal spending and tax receipts as a share of GDP no matter if there are higher or lower tax rates. But the Fed monetized much of the new debt to keep rates artificially lower thereby creating higher inflation as there has been too much money chasing too few goods and services as production has been overregulated and overtaxed and workers have been given too many handouts. The Fed’s balance sheet exploded from about $4 trillion, when it was already bloated after the Great Recession, to nearly $9 trillion and is down only about 6.5% since the record high in April 2022. The Fed will need to cut its balance sheet (see first figure below with total assets over time) more aggressively if it is to stop manipulating so many markets (see second figure with types of assets on its balance sheet) and persistently tame inflation, which there’s likely a need for deflation for a while given the rampant inflation over the last two years. The resulting inflation measured by the consumer price index (CPI) has cooled some from the peak of +9.1% in June 2022 but remains hot at +6.4% in January 2023 over the last year, which remains at a 40-year high (highest since July 1982) along with other key measures of inflation (see figure below). After adjusting total earnings in the private sector for CPI inflation, real total earnings are up by only +2.2% since February 2020 as the shutdown recession took a huge hit on total earnings and then higher inflation hindered increased purchasing power. Just as inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon, deficits and taxes are always and everywhere a spending problem. The figure below (h/t David Boaz at Cato Institute) shows how this problem is from both Republicans and Democrats. As the federal debt far exceeds U.S. GDP, and President Biden proposed an irresponsible FY23 budget and Congress never passed one until the ridiculous $1.7 trillion omnibus in December, America needs a fiscal rule like the Responsible American Budget (RAB) with a maximum spending limit based on population growth plus inflation. If Congress had followed this approach from 2003 to 2022, the figure below shows tax receipts, spending, and spending adjusted for only population growth plus chained-CPI inflation. Instead of an (updated) $19.0 trillion national debt increase, there could have been only a $500 billion debt increase for a $18.5 trillion swing in a positive direction that would have substantially reduced the cost of this debt to Americans. Of course, part of this includes the Great Recession and the Shutdown Recession, so these periods would have likely been good reason to exceed the limit, but regardless we would be in a much better fiscal and economic situation with this fiscal rule. The Republican Study Committee recently noted the strength of this type of fiscal rule in its FY 2023 “Blueprint to Save America.” And to top this off, the Federal Reserve should follow a monetary rule so that the costly discretion stops creating booms and busts. Bottom Line: While there appears to be a strengthening labor market in January, let’s see if this continues as my guess is that these were biased from the data adjustments, and we will see a weaker labor market in the months to come. My expectation is that stagflation will continue along with the a deeper recession this year given the “zombie economy” with “zombie labor” of many workers sitting on the sidelines and others are “quiet quitting” along with the failures of many “zombie firms” that live on debt. Ultimately, Americans are struggling from bad policies out of D.C.. Instead of passing massive spending bills, the path forward should include pro-growth policies. These policies ought to be similar to those that supported historic prosperity from 2017 to 2019 that get government out of the way rather than the progressive policies of more spending, regulating, and taxing. The time is now for limited government with sound fiscal and monetary policy that provides more opportunities for people to work and have more paths out of poverty.

Recommendations:

It's no secret that relocators have recently favored moving to Florida. Recent data from the Florida Department of Motor Vehicles shows that people from New York, New Jersey, and California are among the states with the most people applying for Florida driver's licenses. In fact, according to the New York Post, the data showed that around 30,000 Californians applied for a Florida license in 2022.

Economist Vance Ginn believes he knows one of the major reasons that Californians are coming to Florida, and he believes it is fueled in part by saving money, as follows. Cheaper Housing Fueled by Fewer Roadblocks to Real Estate Development: Ginn, who is chief economist at the Pelican Institute for Public Policy, recently co-authored an opinion piece in the Washington Examiner. In it, he laid out his argument that the primary motivation for relocating Californians to Florida and Texas is housing affordability, writing, in part: "Housing affordability has been a major factor driving Californians to states such as Texas and Florida, where they can realistically afford the American dream of owning a home."Ginn further explains that Florida and Texas have less expensive housing because they implement fewer "bureaucratic bottlenecks" for real estate development, writing: Florida has done a good job winning the war against excessive regulation to make way for more home construction...It’s not complicated: The states and cities that will prosper in the coming decade will be those that allow a less regulated housing market so the quantity of housing supplied can efficiently meet the quantity demanded." U.S. News & World Report did conclude that California was the most regulated state in America. And although Ginn's article is written as an opinion piece, there is some evidence to support some of its claims, as follows. California has 4 of the 10 Most Expensive Cities in the United States: According to a 2022 study by Rocket Mortgage, the markets of San Francisco, Los Angeles, San Jose, and San Diego were among the 10 most expensive cities in the United States, making up almost half of the country's most expensive places to live. Generally Speaking, Housing in California is Much More Expensive than Housing in Florida: Although Florida's real estate markets have risen dramatically, they are still reasonably priced when you compare them to California's. According to Zillow, the average home value in Florida is $404,939. In California, that same number is $760,644. So while some Floridians and those wishing to buy a home in Florida may lament the rising real estate markets, someone coming from California may see Florida real estate prices as a bargain. Differences in State Income Tax: Although Ginn's writings didn't bring up the differences in state income tax, there are key differences between these two states that affect the cost of living. California's state income tax ranges from rates of 1% to 12.3%, and the sales tax rate is 7.25% to 10.75%. Florida does not have a state income tax, and its sales tax rate is 6%. Originally published at Newsbreak. Executive Summary The best path to prosperity is a job. Work brings dignity, hope, and purpose to people by allowing them to earn a living, gain skills, and build social capital that endures. Unfortunately, state and local governments frequently impose regulatory obstacles that hinder this path. Arizona has been at the forefront of removing such hurdles, most recently with the enactment of House Bill 2569. Known as “universal recognition,” this streamlines occupational licensing across dozens of professions by allowing skilled professionals to use their out-of-state experience to quickly obtain a license to work in their new state. Arizona pioneered this approach to help workers relocate, and it is already working, incentivizing even more people to move to the state, and supporting long-term economic growth and job creation. States should follow Arizona’s lead and remove overly burdensome occupational regulations, with universal reforms at the heart of such efforts. Numerous governors have already signed versions of universal licensing recognition into law, and even more are poised to enact the reform in the next few years. In today's solo episode, I use sound economics to break down misleading claims from President Biden's 2023 State of the Union address and share realities on the following (see my recent newsletter for more on this):

Dr. Vance Ginn’s bio (here):

President Biden recently visited the humanitarian crisis along the U.S.-Mexico border but mostly used it as a political stunt to offer more failed policies and chastise Republicans. Republicans have also had years to solve immigration issues, but the situation continues. Meanwhile, Biden and former President Trump have similar protectionist trade policies, which have come at a cost to Americans.

Given the gains from immigration and trade in a globally connected economy, many on the left and the right overlook how government failures of a broken visa system and costly big-government are the source of these problems. And this oversight leads to many of their big-government solutions that aren’t rooted in sound economics but rather winning votes. Immigration and trade overlap in many ways as they are exchanges with people across international borders. Given the rule of law and private property rights are essential in our republic, there are roles for government to enforce the rules of the game but otherwise politicians should address bad policies in the U.S. before trying to blame tangential problems on other countries or “market failures.” For instance, have you ever heard that “immigrants and trade steal jobs”? It’s a myth. The notion that immigrants “steal jobs” supposes that adding more people and different kinds of knowledge and innovation to the economic pie somehow prohibits the native-born population from prospering. Simply put, the aversion to immigrants joining the American workforce is rooted in fear of competition. Moreover, much of the skepticism fueling fear of more working immigrants tends to also be directed at international trade. But the gains to be acquired from immigration and trade outweigh the suspected costs. We would be wise to let markets work within the rule of law instead of imposing arbitrary restrictions and growing government. Working immigrants do not steal jobs. But, as economist Ben Powell recently noted in my conversation with him, they do change the mix of jobs as they expand the capacity of the economy with more workers. Similarly, when young people graduate college and enter the labor market each year, they don’t “steal jobs” but often accept the lower-skilled positions while increasing productivity. These groups support increased competition, fuel the creation of new jobs, and permit the native-born population to work in positions in which they’re more productive. They also increase demand for goods and services provided by lower-skilled workers. So, immigrants and new graduates alike can increase net jobs. When I hire a contractor to install my ceiling fan, I don’t view it as them stealing my job because someone else is better at it. Even though I pay for the service, it’s a trade that ultimately benefits me or I wouldn’t do it, as not learning how to install the fan gives me more time to do things which I enjoy. The contractor and I mutually benefit, just like with all exchanges with people whether in the same community, same state, same country, or another country. Barriers to immigration and trade, such as visa limitations, border walls, tariffs, and quotas, are barriers to human cooperation enforced by politicians with limited knowledge. A more productive path forward would be pursuing immigration reform that improves the visa system, making it easier for immigrants to come legally. Border walls, such as the one in Texas, are a scapegoat and far cry from addressing the real issues needing reform. Similar to the fear of immigration, proponents of trade protectionism often fail to understand that the exchange is as economically simple as it is non-threatening. Whether a Texan is trading with a New Yorker or someone from China, it’s individuals, not places or entities, trading for mutual benefit. A greater exchange of goods and services through trade promotes competition as the expanded pool of resources for consumers encourages producers to innovate to stay competitive or risk closing. International trade doesn’t steal U.S. profits any more than immigrants steal jobs. But, like immigration, it allows people to focus on producing the goods they have a comparative advantage instead of being pressured to supply everything for themselves. The goal should be to reduce costs of doing business so there are abundant opportunities for American workers and businesses to flourish by cutting government spending, taxes, and regulations. Restricting trade and immigration ultimately restricts the prosperity supported by free-market capitalism by keeping out an influx of knowledge, skills, and goods and services that made the American melting pot so great for so long. Anti-trade and anti-immigration are anti-growth. Free markets are really free people. We ought to find free-market solutions to advance freedom and opportunity rather than impose costly barriers that hinder them. As economist Peter Boettke recently in my conversation with him: when ordinary people are given elbow room to grow, economies thrive and people can prosper. Originally published at Econlib. By Victor Skinner | The Center Square contributor | Feb 16, 2023

(The Center Square) – Louisiana’s combined state and local sales taxes are the highest in the nation, a reality critics contend is one of several tax and spending issues plaguing the state. The Tax Foundation released a report last week that compares state and local sales taxes across the nation, ranking states based on both the state sales tax and combined state and local rates. The research shows that as of Jan. 1, Louisiana’s state sales tax of 4.45% ranks 38th from the top. But when that figure is added to the average local tax rate of 5.10%, the state’s 9.55% combined rate becomes the highest among 50 states and the District of Columbia. "Sales taxes are just one part of an overall tax structure and should be considered in context," according to the report. "For example, Tennessee has high sales taxes but no income tax, whereas Oregon has no sales tax but high income taxes. While many factors influence business location and investment decisions, sales taxes are something within policymakers’ control that can have immediate impacts." The report comes as Louisiana lawmakers are studying potential changes to the state’s tax structure ahead of the 2023 legislative session. Vance Ginn, chief economist for the Pelican Institute, contends that excessive government spending is one factor driving higher taxes in Louisiana, though he believes personal income taxes are having the biggest impact on the state’s economy. "We have got to find a way to restrain excessive government spending at the state and local level," he said. "The sales tax is high in Louisiana … but really the focus should be on the burdensome income tax." The Pelican Institute is advocating for a flat income tax that eventually phases to zero. "That will allow for more job creation and economic growth," Ginn said. The Tax Foundation ranks Louisiana 25th nationally for income taxes, 32nd in the nation for corporate income tax, and 23rd for property taxes. Those rankings, combined with other measures, puts the state in 39th place overall in the foundation’s 2023 State Business Tax Climate Index. The foundation’s most recent report notes that sales tax rates can have a significant impact on where residents make major purchases and where businesses locate, and it cites examples of states that have increased per capita sales by maintaining rates lower than their neighbors. The analysis shows Louisiana’s 9.55% combined sales tax rate is more than 2% higher than Mississippi’s 7.07% rate, and 1.35% higher than Texas at 8.20%. Arkansas’ combined rate of 9.46% is the third highest nationally, behind Louisiana and Tennessee at 9.55%. California has the highest state sales tax rate at 7.25%, followed by four states tied for the second-highest rate, at 7%: Indiana, Mississippi, Rhode Island, and Tennessee. Five states do not have a state sales tax: Alaska, Delaware, Montana, New Hampshire and Oregon. The lowest rates for states with sales tax include Colorado at 2.9%, followed by Alabama, Georgia, Hawaii, New York and Wyoming, all at 4%. States with the highest average local sales tax rates include Alabama at 5.25%, Louisiana, Colorado at 4.88%, New York at 4.52%, and Oklahoma at 4.48%. Behind Louisiana with the highest combined state and local sales tax is Tennessee, Arkansas, Alabama at 9.25% and Oklahoma at 8.98%. States with the lowest average combined rates are Alaska at 1.76%, Hawaii at 4.44%, Wyoming at 5.36%, Wisconsin at 5.43%, and Maine at 5.5%. Originally published at The Center Square. Overview

Texans for Fiscal Responsibility’s 3-Step Plan to Eliminate All Property Taxes

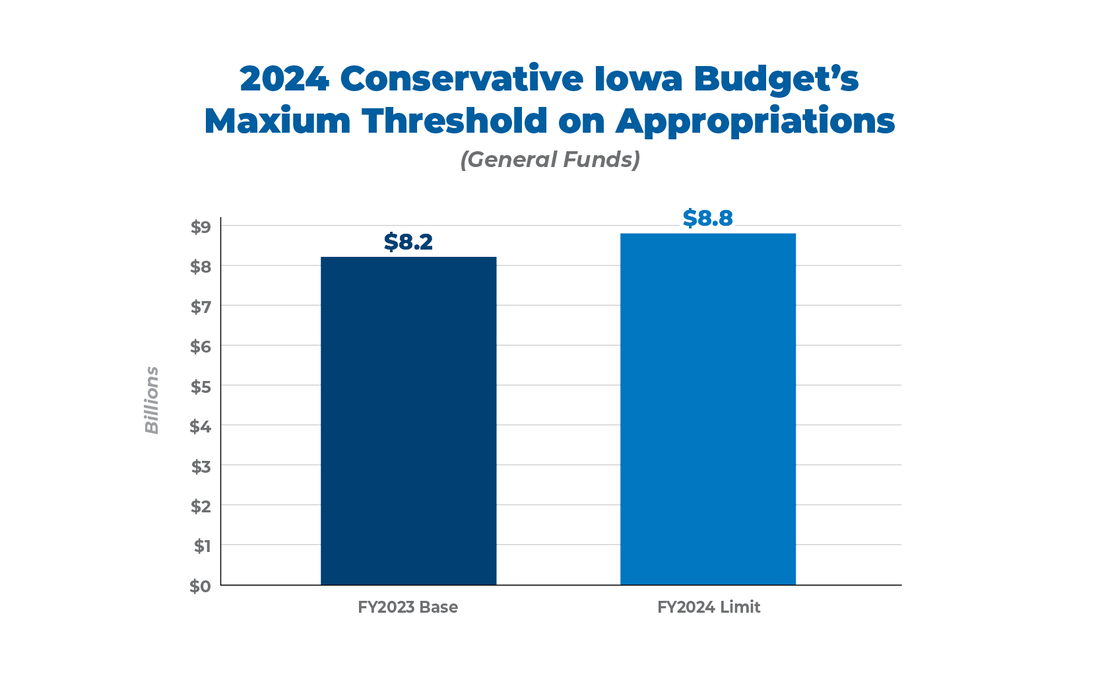

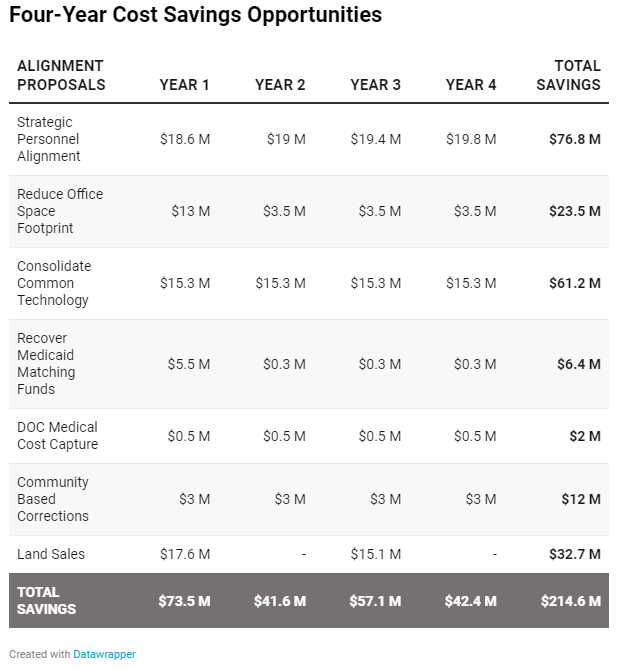

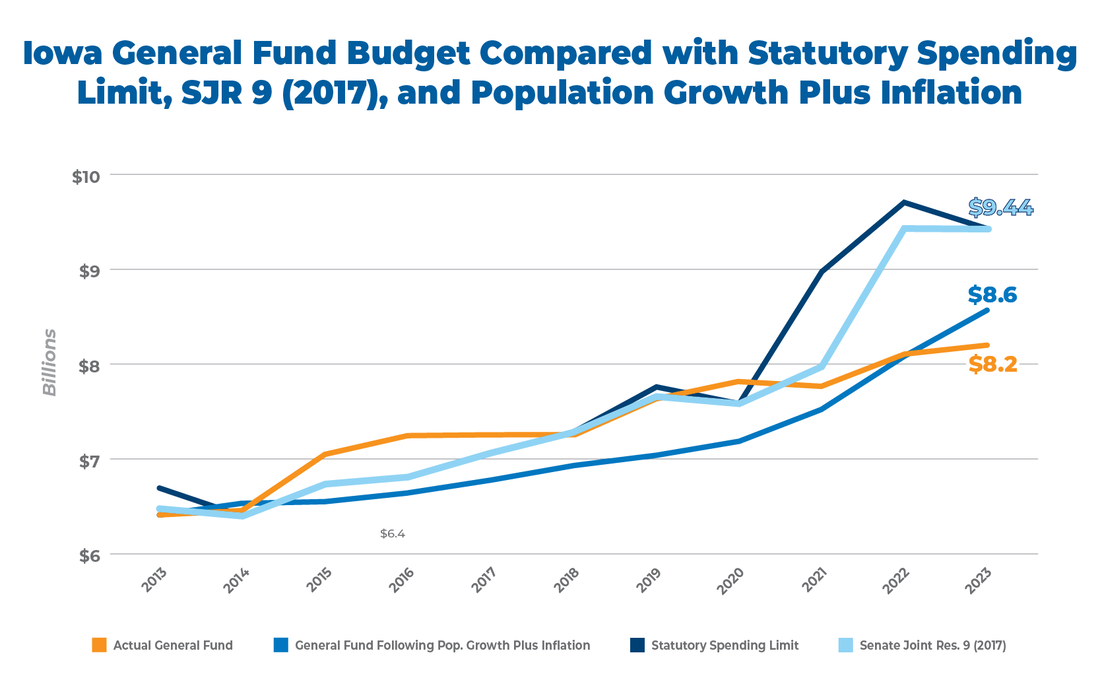

This paper was initially published by Texans for Fiscal Responsibility. Iowa’s taxpayers deserve better constitutional protections against the unquenchable appetite for government spending. Stronger limits can ensure spending remains under control, especially when fiscally conservative policymakers are absent. Introduction Going into the 2023 legislative session, Iowa’s fiscal foundation is strong. The Revenue Estimating Conference (REC), which is a three-person collaboration between the governor’s office and the Legislative Services Agency, is tasked with the difficult job of coming to consensus on the projections the state will use for budgeting. In December, the REC estimated revenue for fiscal year 2023 (FY23) at $9.6 billion. Governor Kim Reynolds used December’s estimate to plan her proposed $8.5 billion FY24 budget. Iowa’s fiscal foundation remains strong despite the national economic uncertainty because of the state’s fiscal conservatism and prudent budgeting. The benefits of this approach are clear. Iowa’s anticipated $1.6 billion surplus for FY23 is nearly as much as the $1.9 billion surplus in FY22, with another $2.2 billion surplus expected in FY24. The state should have $895.2 million in reserve funds in FY23 and $962.5 million in FY24 — the statutory maximum for each year. Additionally, the Taxpayer Relief Fund is on track to increase by $1.6 billion, to $2.7 billion, in FY23, with another increase of $662.6 million in FY24, to $3.4 billion. In short, the state government of Iowa is awash in cash thanks to conservative budgeting. These policies must continue to provide substantial tax relief, and lawmakers can build upon their success by passing a state budget below the recommendation of the Iowans for Tax Relief Foundation (ITRF). Our 2024 Conservative Iowa Budget sets a maximum threshold for general funds of $8.8 billion, based on 7.4 percent rate of population growth plus inflation (see Figure 1). Governor Reynolds’ budget proposal meets this goal. The House and Senate now must offer up their budget targets and then all three proposals will have to be meshed together. Spending restraint when crafting the state’s budget is always important, as it protects taxpayer dollars now and in the future. Figure1. Source: Condition of the State: Vision for Iowa, State Budget FY 2024, Governor Kim Reynolds and Lt. Governor Adam Gregg Going a step farther, the state should write the Conservative Iowa Budget principles into its constitution or statutory code. Thus, Iowa would assure residents and businesses that it will continue to improve as a place to live, raise a family, and start a business, which will in turn strengthen the state’s trajectory. Recent Iowa Budget In its Fiscal Policy Report Card on America’s Governors 2022, the Cato Institute ranked Governor Reynolds as the best in the nation. “Governor Reynolds has been a lean budgeter and dedicated tax reformer since entering into office in 2017,” wrote Chris Edwards and Ilana Blumsack, authors of the report. Last year, Governor Reynolds and the Iowa Legislature continued to place a priority on prudent budgeting. The budget for FY23 was $8.2 billion, increasing by just 1 percent from the prior year. In 2022, Iowa also enacted the most comprehensive income tax reform package in the nation — the largest in state history. Over four years, the nine-bracket income tax will transform into a flat tax with a 3.9 percent rate. The corporate tax will also gradually shrink until it reaches a flat 5.5 percent rate and has already been reduced from 9.8 percent to 8.4 percent. These measures constitute a sound pro-growth tax policy that will create incentives to work, save, and invest. On the national stage, this tax reform will make Iowa’s economy more competitive. Prudent budgeting is essential toward ensuring these income tax rate reductions can be responsibly implemented. Even with national economic uncertainty, Iowa’s revenue continues to grow, reducing the degree to which the tax cuts must be “paid for” through spending restraint. Governor Reynolds has reaped additional benefits from a fiscally conservative agenda with an executive order imposing a moratorium on regulations. Furthermore, state agencies must begin reviewing existing regulations to determine their relevance and economic impact to ensure “existing rules — each and every one — are worth the economic cost,” as Governor Reynolds stated. “Only those that meet this standard will be reissued. The rest will be repealed. When it’s all said and done, Iowa will have a smaller, clearer, and more growth-friendly regulatory system.” Agencies have four years to complete the review process. The governor is also proposing to rein in the administrative state by streamlining government, consolidating the 37 cabinet-level agencies to 16. The process has already begun, and the governor’s office estimates consolidating agencies and other administrative reforms will save taxpayers close to $215 million over the next four years. Source: Condition of the State: Vision for Iowa, State Budget FY 2024, Governor Kim Reynolds and Lt. Governor Adam Gregg Need for Stronger Spending Limits Most states have some form of TEL in statute or (less commonly) in the state constitution. A strong limit can ensure spending remains under control, especially when fiscally conservative policymakers are absent. However, not all TELs are created equal. An effective limit should be determined by the average taxpayer’s ability to pay for the priorities of government, not the appropriator’s cost of providing them. Iowa has a weaker spending limitation than many states: a fiscal rule in state statute restricting the legislature to spending no more than 99 percent of estimated revenue. Efforts in the Iowa Legislature to strengthen this limit have proven unsuccessful, so far. Most recently, the Iowa Senate passed Joint Resolution 9 in 2017. This constitutional amendment would have limited the annual increase to the lesser of 99 percent of the estimated revenue or 104 percent of the prior year’s revenue. (Historical comparisons including the existing and proposed rules are visible in Figure 3 below.) Iowa’s taxpayers deserve better constitutional protections against the unquenchable appetite for government spending. Families and businesses must make difficult budget decisions on a regular basis; this experience should not be so rare in government. With spending limitations in place, argues economist Daniel J. Mitchell, “politicians are forced to abide by the rules that apply to every household and business in the state. In other words, they have to prioritize,” Colorado has shown this principle in practice. In 1992, voters adopted the Taxpayer Bill of Rights (TABOR), which was a constitutional amendment limiting government spending of most general funds at the state and local levels to a maximum rate of population growth plus inflation. Voters must also consent to spending increases above that level. If revenue exceeds the limit, the money returns to taxpayers as tax rebates. Unfortunately, progressives have weakened Colorado’s TABOR over time, and the tax rebates have encouraged dependency on government rather than translating into tax rate cuts. Nonetheless, since its enactment, TABOR has returned $8.2 billion to taxpayers. Other states enacted measures similar to TABOR, proving that different approaches can be successful. Kurt Couchman, a Senior Fellow with Americans for Prosperity, argues that a “rules-based structural balance is a promising alternative,” focusing on the following:

“Structural balance can provide both short-term policy stability and long-term fiscal responsibility,” according to Couchman, putting pressure on the growth of spending and utilizing debt brakes and revenue limits Texas also has implemented a strong spending limitation. In 2021, the legislature codified a new spending limit in SB 1336, which is arguably now the strongest in the nation. Based on the Texas Public Policy Foundation’s Conservative Texas Budget, the new spending limit sets a cap on all general revenue based on the rate of population growth and inflation. Exceeding the cap requires a three-fifths vote in both chambers of the legislature. “This change effectively puts tax relief on Texas’ permanent agenda. Policymakers can lock in tax relief by tying Texas’s future fiscal surpluses to automatic tax cuts,” writes Michael Lucci, a senior fellow at the State Policy Network. Because spending and tax limitations can take various forms, Matthew Mitchell, now a senior fellow at the Fraser Institute, contends the most effective will:

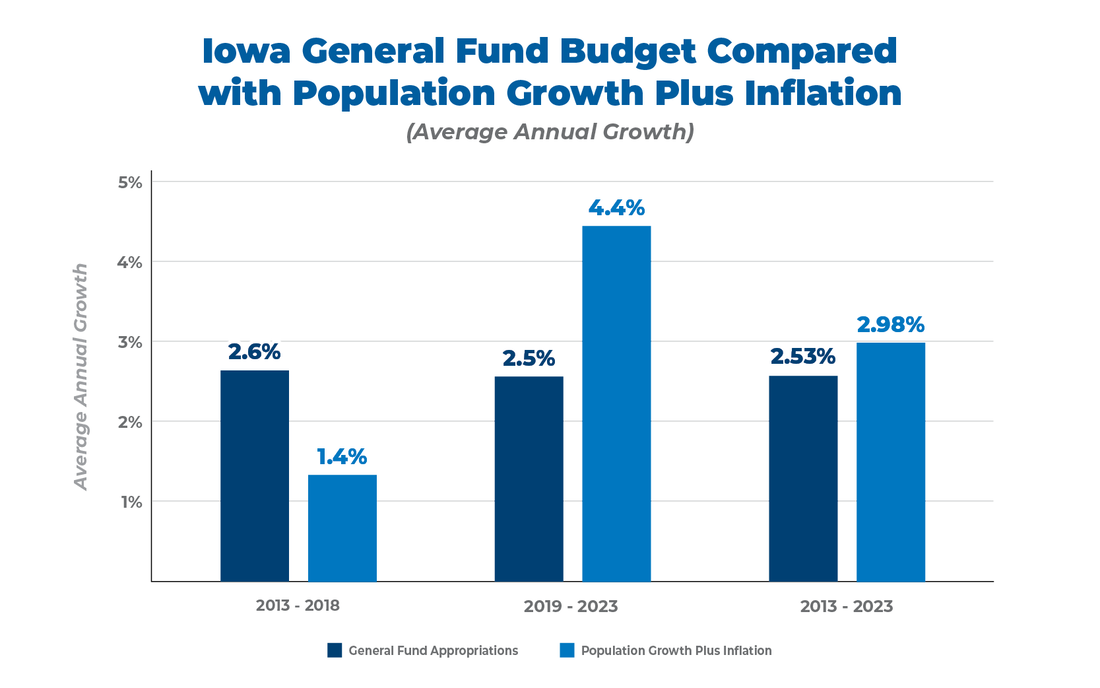

Joining these guidelines with the examples described above, the ideal limit would cover the broadest base of the budget possible, with a maximum growth rate limited to population growth plus inflation. It would also return the resulting surplus funds to taxpayers through reduced tax rates, not tax rebates. Such a policy would give Iowa the strongest spending limit in the nation and solidify responsible budgeting in law for a consistent, predictable future. President Calvin Coolidge regarded “a good budget as among the noblest monuments of virtue,” and it is incumbent upon Iowa’s lawmakers to be virtuous in this way. Historical Iowa Budget Figure 2 compares Iowa’s General Fund increase over the past decade with the state’s population growth plus inflation, as measured by the U.S. Chained Consumer Price Index (CPI). While the growth of appropriations has been below this benchmark for the full period, that result is attributable solely to the fiscal responsibility of the last four years. Figure 2. The relative recency of this proper balance places a spotlight on the need to implement policy to prevent backsliding. Figure 3 illustrates the current statutory spending limit’s failure to control appropriations over time. Its weakness has allowed excessive growth in the budget over time. The figure also shows that Senate Joint Resolution 9 would also have been insufficient. Figure 3. In contrast to Iowa’s existing revenue-focused method, setting a spending limit that tracked with population growth plus inflation would have provided even more restraints on the expansion of government since 2013, leading to more conservative budgets and greater opportunities for tax relief. In fact, actual budget growth above this measure has been a cumulative $2.9 billion since 2013, meaning that taxes Iowans paid over that time period could have been at least $2.9 billion less . Put differently, an average family of four has paid nearly $3,700 more in taxes than if the state had adhered to a different spending limitation.

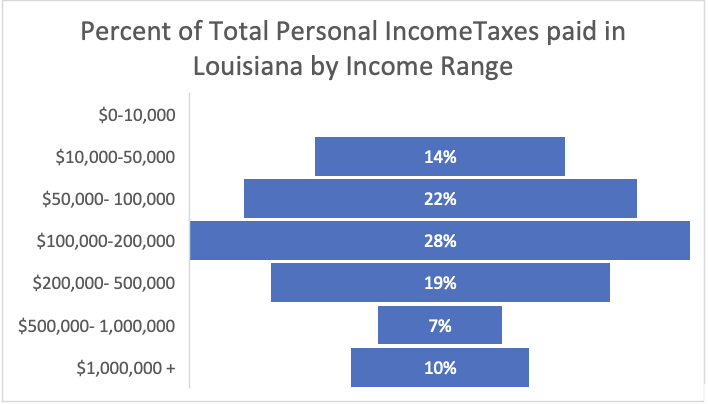

Conservative Iowa Budget Iowans are fortunate that in recent years the governor and legislature have been budgeting in the spirit of the Conservative Iowa Budget. Even without a stronger state spending limit, the fiscal discipline exhibited by lawmakers has contributed to large surpluses and tax reforms and relief. To continue this conservative trend, ITRF is releasing the FY24 Conservative Iowa Budget with a maximum threshold of $8.5 billion, based on the summed rate of 7.4 percent. This target combines the 0.2 percent rate of state population growth with the 7.2 percent rate of U.S. chained-CPI inflation in 2022. Holding the Iowa state government’s budget to this level will provide opportunity for tax relief in the face of economic headwinds from bad policies out of D.C. A 40-year-high level of inflation (without corresponding wage growth) and market corrections responding to Congressional overspending, President Biden’s overregulating, and the Federal Reserve’s overprinting of money, make well-considered and consistent tax policy imperative. Conclusion Iowa has been at the forefront of conservative budgeting in the United States. This approach has left more money in taxpayers’ pockets with a substantial tax relief package headed toward a low flat tax by 2026. This process must continue to ensure Iowans’ flourishing. Fortunately, Governor Reynolds’s FY24 budget proposal continues her practice of fiscal prudence. Limits on spending will be paramount for further income tax reform, and the governor has already signaled that Iowa will not be complacent at 3.9 percent. Talk of lowering the income tax rate to a flat 2 percent with a pathway to eventually eliminating the tax keeps the focus where it ought to be. Rejecting complacency is important when it comes to state-government spending, too. A stronger spending limit will not only help to protect the interests of taxpayers, but it will also keep the growth of government in check. On its current path, Iowa can expect a robust economy, a flourishing civil society, and prosperous people, but the work of getting government out of the way while funding basic services is not complete. Originally published at Iowans for Tax Relief Foundation. Fairness, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder. This popular sentiment is certainly true in a free market where buyers and sellers determine prices instead of a third party picking winners and losers. Unfortunately, taxes in Louisiana and other states get caught up in this subjective determination when the questions that really matter are what will help more Louisianans stay in the state, and what will bring them well-paying jobs along the way? A recent presentation by Together Baton Rouge before Louisiana’s House Ways & Means Committee made the case that the state’s tax code is unfair. They pointed to research by the left-leaning Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP), which considers the distributional effects of tax systems in each of the 50 states. And as you’d expect, ITEP considers those states without a personal income tax as the most regressive because low-income earners tend to pay a larger share of income to taxes than upper-income earners. The fact, however, is that the majority of Louisiana’s individual income tax revenue is paid by middle and higher-income earners, as reported by the Louisiana Department of Revenue in its annual report. ITEP’s analysis finds that “Louisiana has the 14th most unfair state and local tax system in the country.” And while that’s true in many respects, it’s not necessarily because of rising income inequality as some suggest.

Recent Census data show that people are continuing to leave Louisiana. This is a drain on innovation and job opportunities, so there’s less incentive for businesses to stay. Why would the state resort to trying to smooth the distribution of income, which would inevitably mean raising taxes on entrepreneurs who start businesses and hire workers? Instead, lawmakers’ next steps should be to restrain spending and flatten income taxes until they can be eliminated. This process was started in 2021 by lowering all the personal income tax rates, further stipulating that future increased revenue should “trigger” even lower income tax rates, which could potentially go into effect beginning next year. The state is currently seeing record levels of revenue. In fact, Louisiana is set to have an additional $1.6 billion to use in this fiscal year alone, and there is already an increase of $600 million above current revenue expected for the next fiscal year. But there is a lot of uncertainty surrounding whether the state will hit its revenue targets in future years due to economic downturns and record spending increases. If it does, the state would benefit from the lower tax rates by fueling economic growth. More should be considered in the 2023 legislative session beyond just cutting existing rates. Lawmakers should consider flattening income taxes to just one bracket with a single, low rate for everyone. This is what research has proven effective to incentivize people to work and take risks, much more so than continually taxing their innovative prosperity. Given these factors, a flat income tax would help everyone who pays taxes have skin in the game instead of trying to pick winners and losers. Higher-income earners would still pay much more in taxes with a flat tax rate because their income is higher. Fairness can be a factor, but it shouldn’t be the overarching factor when deciding tax law. The best taxes are those that are broad-based with the lowest flat rate possible, and ultimately without income taxes. This would be fair to workers and the flourishing of Louisianans for many years to come. Originally published at Pelican Institute. California Gov. Gavin Newsom boldly — and a wee bit desperately — ran ads last summer encouraging Florida residents to relocate to California . Housing affordability is one reason it probably won't work.

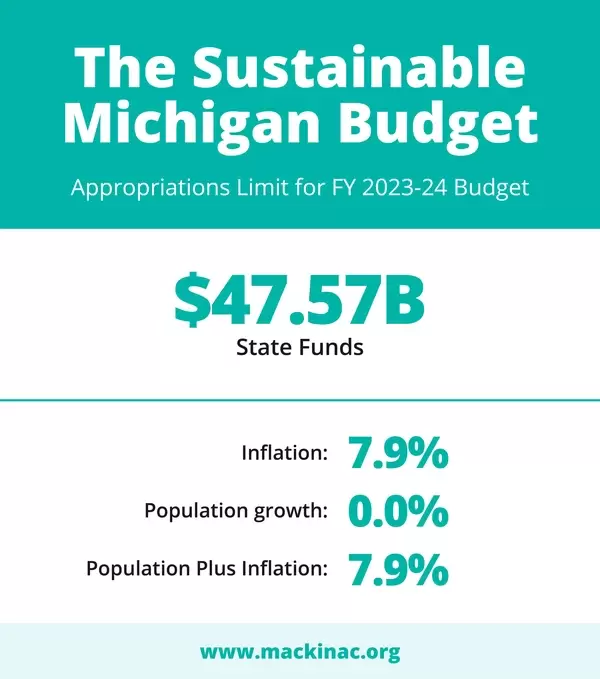

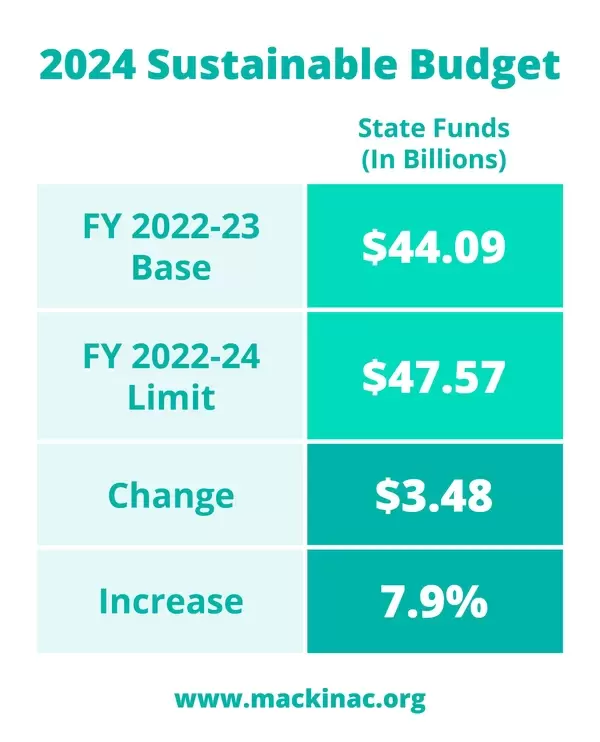

Housing affordability has been a major factor driving Californians to states such as Texas and Florida, where they can realistically afford the American dream of owning a home. Cost of living — which is mainly a housing problem — and taxes round out the top motivations for fleeing the once-growing states such as California. The states that win on housing affordability from free-market-oriented policy win overall. Twenty years ago, few would have bet on a mass exodus of residents from the popular albeit highly regulated housing market in California. Issues related to land use, zoning, and bureaucratic chaos led to substantially higher housing costs. The five most expensive housing markets nationwide are all within California. Further, a recent Hoover Institution report found that one of the top reasons companies leave California is “... high living costs, particularly the cost of housing affordability.” In the same vein, C2ER finds that California’s housing costs are about 1.7 times greater than Florida’s and 2.2 times higher than Texas’s. This contributes to California suffering losses of big businesses (11 Fortune 1,000 companies) between 2018 to 2021, along with small, quickly growing companies. Texas and Florida have figured out the secret to housing affordably through free-market policies that help entrepreneurs address challenges to build more homes in a safe, less costly manner. The recent census report shows how Florida drew the most net new domestic residents (318,855), with Texas coming in second (230,961). Many people packed up and moved to states with “lower taxes, more affordable housing and a higher standard of living.” What’s more, Texas came in first in overall population growth (470,708), with Florida second (416,754). These states are the ones that tend to let builders build more freely than the others. The Wharton Residential Land Use Regulation Index , one of the most respected analyses of the effect of regulation on price, shows a strong, positive correlation between house prices and over-regulation. Take, for example, San Francisco, where it takes 861 days to get a permit for one residential home. In Houston, it takes just 15 days . That’s huge savings for homebuilders and, therefore, homeowners. For Texas to remain competitive, it must guard against bureaucratic bottlenecks like those developing in Austin, where simply getting residential site plans approved now takes one to two years . To remain prosperous, Texas must keep and improve on free-market principles, especially in housing. Otherwise, the resulting higher costs of living will force people and businesses elsewhere. Florida has done a good job winning the war against excessive regulation to make way for more home construction. In 2019, the Sunshine State passed a law allowing third parties to help streamline the permitting process, alleviating wait times for home construction. In 2021, it passed a shot-clock law that effectively limited permit responses by cities to no more than 30 days. It’s not complicated: The states and cities that will prosper in the coming decade will be those that allow a less regulated housing market so the quantity of housing supplied can efficiently meet the quantity demanded. For states that plan to attract business while retaining residents, they must improve the regulatory environment for builders by getting out of the way. This should include streamlining building regulations to make it easier to build new housing, reforming land use policies to encourage development, and sorting out the bureaucratic bottleneck that complicates the building process. Like musical chairs, if you have fewer chairs than people, some people have to find a new home … or a state. Vance Ginn, former associate director for economic policy in the White House Office of Management and Budget, is president of Ginn Economic Consulting, LLC , chief economist at Pelican Institute for Public Policy, and senior fellow at Young Americans for Liberty. Nicole Nabulsi Nosek is the founder and chair of Texans for Reasonable Solutions. Originally published at Washington Examiner. Michigan lawmakers should be careful about the upcoming year’s budget. There is a lot of uncertainty about what is coming, but lawmakers have more than $8 billion in extra cash on their hands. They should adopt a Sustainable Michigan Budget to ensure that spending grows no more than the average taxpayer can afford. That means spending no more than the rate of the state’s population growth plus inflation. Because of the recent spike in inflation, this gives the state more money to spend in the upcoming budget even though population declined slightly in 2022. Michigan lawmakers initially budgeted $44.09 billion in state funds last year, excluding federal transfers and small amounts of local and private money. Lawmakers should approve a 2023-24 budget that pledges to spend no more than $47.57 billion in state funds. The benefits of budget restraint are clear. It gets lawmakers to prioritize limited taxpayer funds and ensure residents get the best return on their dollars. Due to past excesses, the budget has grown to be $6 billion [HJM1] more in the 2022-23 budget than it would be if it had followed the rate of population growth plus inflation over time. This amounts to $600 more dollars in taxes and fees paid per resident and more than $2,400 more, on average, for a family of four. Instead of following a sustainable spending pattern, Lansing has added many items to the budget that limit the state’s ability to address priorities. Lawmakers added $1 billion worth of special grants for 149 select projects at the last minute of last year’s budget cycle. Without an open process and established criteria, lawmakers simply waste money on politically directed spending. The Sustainable Michigan Budget also ensures that legislators remain flexible.

Michigan has a balanced budget requirement, and lawmakers tend to interpret that as a recommendation to spend all of the collected tax revenue. This doesn’t give lawmakers a lot of room to respond to unexpected needs, like increased demand for Medicaid in the event of an unexpected recession. Plus, the desire to spend all tax revenue puts pressure on lawmakers to increase taxes if revenue drops or falls unexpectedly. Passing the Sustainable Michigan Budget ensures legislators will have resources available to deal with an uncertain future. The most important benefit is sustainability. Spending less than the rate of population growth plus inflation would allow lawmakers to leave more money in taxpayers’ pockets while sufficiently funding limited government provisions. It provides certainty to Michigan residents and businesses about what the state government is going to collect each year and sets those rates at what taxpayers can afford. Slowing spending on current services also means that the state can fix a lot of its long-term financial problems. Lawmakers accidentally made school employees the state’s largest creditors by not saving enough to pay for all of the pension benefits promised to employees in the state-managed pension system. This is bad for teachers and taxpayers alike. Lawmakers can secure these pensions and save billions by using savings on current services to pay down pension debts. Michigan has new legislators and new Democratic majorities in both legislative chambers. They will have different priorities on which spending is important to them than the last legislature. One of their priorities ought to be for the growth of Michigan’s budget to be sustainable. It will take some restraint on their part not to spend every dollar they have available. This would improve the state’s financial position, require more judicious budgeting, and ensure that the state government remains sustainable. Originally published at Mackinac Center for Public Policy. The Pelican State has tremendous opportunity and potential.