|

Originally published at James Madison Institute.

America’s Antitrust laws have been essential to the legal landscape for over a century. They were designed to protect competition and consumer welfare. However, the Biden administration’s onslaught on competition through flawed antitrust efforts has threatened consumer welfare and profitability. This is especially true for “Big Tech” companies that generate substantial consumer welfare and billions of dollars in economic activity. While these efforts are purportedly aimed at safeguarding the interests of consumers, they pose a major threat to free-market capitalism and, thereby, the nation’s prosperity. Understanding the origins of antitrust laws illuminates why current antitrust accusations are far from their original purpose. Antitrust laws trace back to the Sherman Anti-Trust Act’s enactment in 1890. The landmark legislation was aimed to curb anticompetitive practices. Section 1 prohibits contracts in restraint of trade, regardless of the size of the firms participating. Section 2 prohibits monopolization or the abuse of monopoly power by firms with substantial market shares. Further reinforcement came with the Clayton Act in 1914, which focused on preventing mergers that could substantially lessen competition or tend to create a monopoly. However, applying antitrust laws lacked consistency and often yielded ambiguous results, especially during the mid-20th century. Fast forward to the 1970s, legal scholars proposed a paradigm shift. Figures like Aaron Director, Robert Bork, and others delved into the legislative history of the Sherman Act, concluding that its primary purpose was to protect consumers from the harm caused by cartels without undermining economic efficiency. This approach laid the foundation for what we now call the consumer welfare standard, a critical development in antitrust enforcement. In the late 1970s, the U.S. Supreme Court recognized this standard in several cases, asserting that business conduct raising antitrust concerns must be evaluated based on demonstrable economic effects. This standard has since guided antitrust law, emphasizing a simple question: does the conduct make consumers better or worse off? If the conduct improves or does not harm consumers, the conduct is allowed; otherwise, the government can intervene. The consumer welfare standard is a seemingly straightforward approach that has been a guiding light to antitrust cases. But it has failed to hold those currently at the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and Department of Justice accountable for their excessive efforts. In recent years, calls to wield antitrust laws to address the conduct of prominent technology companies like Amazon and Google, which some pejoratively call “Big Tech,” have gained momentum. However, these movements are misguided and pose significant risks to the principles of free-market capitalism. Expanding the enforcement powers of antitrust agencies, as advocated by some on the left and right, revives an old “big is bad” approach reminiscent of a bygone era when antitrust enforcement was highly politicized. Instead of fostering competition, such a progressive approach undermines the competitive market process. This destroys the instrumental activity that provides innovation, affordable prices, and high-quality goods and services, all critical for human flourishing. This lawsuit purports to challenge Amazon’s management of its online marketplace, alleging that sellers are forced to charge high prices and lose profit by using Amazon’s add-on services and advertisements. The FTC contends that these choices are obligatory and accuses Amazon of operating as a monopoly, leading to higher prices for lower-quality products. Numerous surveys and studies reveal that consumers are pleased with Amazon’s services, so this attack against the consumer welfare standard does not appear to be about what is best for customers despite the claims of progressive antitrust enforcers. Moreover, consumers have the agency to take their dollars elsewhere, as Amazon is hardly the only online seller. The principles that drive capitalism are rooted in competition; when competition is stifled, consumers and entrepreneurs lose. Another example of abusing antitrust is the Department of Justice’s (DOJ) lawsuit against Google. The suit contends that Google has dominated the market as the default browser on popular devices through monopolistic means and must be stopped. However, Google is the default browser via legal marketing tactics, which the consumer can easily change, as numerous search engine options can be implemented on any device. Therefore, the case fails to meet the standard of a solid antitrust law violation of making consumers worse off. Consumers still have many options when selecting a default browser, but most choose Google because they like it best. This lawsuit is emblematic of a broader issue – applying antitrust laws to preserve competition. Antitrust laws should protect consumers by evaluating whether they are better or worse off due to a company’s actions. It should not be a mechanism to stifle competition to level the playing field. Enforcing such laws without considering the diverse preferences of consumers is a disservice to the very principles on which capitalism–and antitrust laws–were founded. If we’re going to have antitrust laws rather than just letting market forces work, the consumer welfare standard is an essential framework for evaluating antitrust cases. It ensures that the focus remains on improving people’s lives rather than manipulating the market based on antitrust enforcers’ interests or political persuasions. This standard can help keep regulators from blocking innovation and economic growth by limiting their ability to pick winners and losers. While concerns about the size of large tech companies and their censorship practices may be warranted, granting more power and discretion to government bureaucrats is not the solution. Expanding antitrust laws and enforcement powers will lead to politicized enforcement, often aimed at serving the interests of big government, with a disregard for the effects on consumers and the broader economy. Such a big-government approach would curtail entrepreneurship, freedom of speech, job creation, investment, and economic prosperity. Proposals to create new antitrust laws are unlikely to address concerns related to censorship and bias in tech companies. Instead, they will usher in uncertainty as legal standards evolve, causing companies to settle such cases to avoid costly legal battles. Such settlements may not necessarily benefit consumers or the economy and will drive up entry costs, creating a high barrier for startups. At a time of elevated inflation, the labor market faces challenges, and the economy is in turmoil. Pursuing lawsuits against successful companies diverts resources from critical issues and misuses taxpayer money. The time is now to refocus on what genuinely matters, acknowledge the limitations of government intervention in regulating markets, and allow the principles of free-market capitalism to flourish. This approach should recognize that dispersed, decentralized information through people in markets is much better than through central planning. Free-market capitalism is not the enemy but the best path to prosperity and freedom. We would be wise to have more of it, not destruction by the radical Biden administration.

0 Comments

Originally published at Daily Caller.

The Biden administration wants to cap credit card late fees through the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB). But hold on – this could spell trouble, especially for those the rules intend to help. The CFPB’s proposed rule to cap credit card late fees may reflect a well-intentioned effort to enhance consumer protection, suggesting that lower-income households may be hurt the most. However, stakeholders, including the American Bankers Association, caution against doing so because of many unintended consequences. These include restricting access to credit for those in need, creating perverse incentives to not pay on time, and raising the cost of banking and credit by passing along these costs to everyone. Late fees may be a nuisance, but they’re crucial to keeping credit card systems in check and getting credit to those who need it. By capping late fees at $8 and limiting them to 25 percent of the minimum payment, the CFPB risks upsetting the delicate balance of the financial ecosystem. Whether we like it or not, credit cards serve as a lifeline for millions of Americans, offering convenience, security, and a way to build credit. Indeed, for families living paycheck to paycheck, every dollar counts. But it’s imperative to point out that late fees are not solely punitive measures. Late fees encourage people to pay on time, reducing defaults and helping provide needed access to credit. But if late fees get capped, it’s not just the big banks that’ll feel the pinch – it’s everyday people and small businesses. Banks will likely raise fees or tighten lending standards to compensate for lost revenue. That means higher costs and less access to credit for everyone. Economist Dan Mitchell’s analysis highlights the unintended consequences of well-intended regulations and urges policymakers to tread carefully. Late fees contribute significantly to the bottom line for card issuers, but they also influence consumer payment patterns and debt management strategies. Imposing price controls like these on the marketplace isn’t free. People in the marketplace are best at pricing things, including credit card late fees. Government-imposed restrictions, such as caps on late fees, will distort market signals and hinder economic efficiency. In Texas, where local banks are the backbone of many communities, as in many other states, this policy could hit especially hard. If banks can’t use late fees to encourage timely payments, businesses might struggle to get the credit they need to grow and thrive. In fact, Glenn Hamer, president of the Texas Association of Business, recently noted the symbiotic relationship between late fees and small depository institutions. Many local banks rely on late fees to cover operational costs and extend credit to consumers. Imposing strict limits on late fees could jeopardize the viability of these institutions, limiting access to credit for underserved communities. The Small Business Regulatory Enforcement Fairness Act (SBREFA) underscores the importance of assessing the impact of regulatory proposals on small businesses. Late fees are a lifeline for small depository institutions, enabling them to compete in the credit card market. Any regulatory changes must carefully consider the implications for these businesses and the communities they serve. Economist Milton Friedman warned: “Many people want the government to protect the consumer. A much more urgent problem is to protect the consumer from the government.” Before the CFPB rushes into this, let’s pump the brakes. Because when it comes to late fees on credit cards, or “junk fees” in general, one size does not fit all. Originally published at The City Journal.

In November 2023, Texas voters approved a constitutional amendment, HJR 2, which Governor Greg Abbott said would “ensure more than $18 billion in property tax cuts—the largest property tax cut in Texas history.” Texas homeowners’ hopes were dashed at the start of 2024, however, when they got their property tax bills. The promised $18 billion reduction amounted to only $12.7 billion in new property tax relief, a fraction of the state’s record $32.7 billion budget surplus, while the other $5.3 billion merely maintained property tax relief from years past. While Texas doesn’t have a state income tax, it does have the nation’s sixth-most burdensome property taxes. These taxes obstruct peoples’ ability to buy homes and price others out of the homes they’re in. Texans expect and deserve clarity about their property tax bills, but state policymakers’ failed promises and lack of transparency have eroded public trust. Despite the governor’s claim, the 2023 tax relief package, spread over two years, isn’t even the state’s largest historic property tax cut. In 2006, the Texas legislature apportioned $14.2 billion to reducing residents’ property taxes, cutting school district maintenance and operations (M&O) property tax rates by a third for 2008–09 biennium, and making up the difference with a revised franchise tax, a higher cigarette tax, and a higher motor vehicle sales tax. Adjusted for inflation, 2023’s cut would have had to exceed $21 billion to surpass the 2006 cut. The new package's biggest achievement was saving taxpayers $5 billion in 2023 by reducing the maximum school district M&O property tax rate by 10.7 cents per $100 valuation; it also raised the homestead exemption of taxable value for school district M&O property taxes to $100,000 and limited appraisal-value increases to 20 percent for other property. And yet, Texans’ total property taxes paid in 2023 nevertheless rose by $165.2 million over 2022, an overall increase of 0.4 percent. That net increase came from school district tax hikes to fund more debt ($890.2 million); municipal governments ($1.3 billion); county governments ($1.5 billion); and special purpose districts ($1.5 billion). These hikes effectively washed away state-level reductions. While this result is ultimately the fault of local governments, the state should have done more to provide relief and restrict localities’ spending and taxes. This growth in local property tax collections is part of a larger trend. From 1998 to 2023, Texas’s total property taxes collected rose 338 percent while the rate of population growth plus inflation was just 136 percent. No wonder so many Texans feel as though they are being crushed by housing unaffordability. How can Texas fix its spending problem? Rather than resort to temporary fixes, the state needs a robust spending cap in its constitution like Colorado’s Taxpayer’s Bill of Rights (TABOR), which limits state and local government spending increases to no more than the rate of population growth plus inflation. Though Colorado’s TABOR has been the gold standard for a state spending limit since its enactment in 1992, it can be improved. At this time, TABOR applies to Colorado’s general revenue, less than half of its total funds; it should be expanded to apply to all state funds, which would account for about two-thirds of its budget, as originally intended. Texas, or Colorado itself, could also improve the model by replacing the latter’s policy of refunding excess tax revenue to taxpayers with up-front income-tax-rate cuts. Texas enacted a statutory spending limit in 2021, but it lacks teeth, as an overriding constitutional spending limit covers just 45 percent of the budget and can be exceeded by a simple majority. In conjunction with a stronger constitutional spending limit, the Texas legislature should implement strategic budget cuts. These efforts combined with the stricter constitutional spending limit would create opportunities for surpluses at the state and local levels, which would pave the way for the state to reduce school M&O property taxes annually until they are fully eliminated. This alone would shave off nearly half of the property tax burden in Texas. Viewed from the coasts, Texas is a beacon of economic freedom. But as its spending and property tax data show, it isn’t perfect. The Texas legislature should acknowledge its failed promises and deliver real property tax relief for its citizens. Episode 85 is with Dr. Adam Michel, director of tax policy studies at the Cato Institute.

Today, we discuss: 1) Problems with OECD and global taxes; 2) Tax cliff coming in 2025 from many expiring TCJA provisions; and 3) Why a fiscal crisis without major spending reforms, how taxes influence human behavior, the truth about The Laffer Curve, and much more. Please like and comment on this video, subscribe to the channel, share it on social media, and provide a rating and review. Thanks! Also, subscribe and see show notes for this episode on Substack (www.vanceginn.substack.com) and visit my website for economic insights (www.vanceginn.com). In today’s This Week’s Economy episode 49, I provide a trigger warning about my 10 unpopular views, housing deregulation, property taxes, Gen-Zers moving to Texas, and much more. Please like this video, subscribe to the channel, share it on social media, and provide a rating and review. Also, subscribe and see show notes for this episode on Substack (www.vanceginn.substack.com) and visit my website for economic insights (www.vanceginn.com).

Originally published at Dallas Express.

National School Choice Week was last month, a time when all states should be celebrating the educational freedom they provide to teachers, parents, and, most of all, students. Sadly, only about 20% of states have embraced universal school choice, with Texas being among the 80% failing to partake in the school choice revolution. Texas leads the nation in many respects, but our educational landscape continues to lag behind. Without universal school choice, we will continue regressing, compelling families to seek superior educational options elsewhere. The consequences of this regression are already evident, making it imperative for Texas to act. School choice through education savings accounts (ESAs) would allow families to direct their money for their children’s education to approved schooling providers. These include traditional public schools, charter schools, private schools, virtual learning, co-ops, and homeschooling. ESAs are the gold standard for school choice, and 13 states have already adopted them. ESAs put the power in the hands of parents, where it should be, by giving them the funds for education to choose which schooling best meets their kids’ unique needs. It’s essential to distinguish ESAs from controversial “vouchers,” as ESAs offer a more comprehensive range of educational choices. Rather than funding following the child from a government school to a private school with vouchers, the funding goes to the parents, who decide how to use it with ESAs. This also helps break the connection between dollars going directly to an institution where politicians and bureaucrats can regulate. Instead, ESAs give freedom for different types of schooling to compete in a market without the many rules that hamper government schools today. While there was a glimmer of hope in late 2023 for Texas to pass ESAs, the legislation, which had many problems, failed due to insufficient support from Democrats and rural Republicans. This setback carries considerable weight, particularly when other states embrace the competition and innovation accompanying universal school choice. Texas can’t afford to be left in the shadows. The consequences of our state’s hesitancy in progressing toward educational freedom are evident. According to The Heritage Foundation, between 2007 and 2022, rural Texans, a group purportedly opposed to school choice, witnessed a 20-point decline in 8th-grade math scores and a 12-point decrease in 8th-grade reading. Regarding 8th-grade reading scores across the state, we are four points below the national average. The subpar results are disturbing, with Texas spending an average of nearly $15,000 per student. Moreover, the pandemic has underscored the need for flexible and diverse learning options. Families faced unprecedented challenges during school closures, revealing the shortcomings of a one-size-fits-all educational approach that left substantial learning loss. Universal school choice can serve as a crucial buffer, ensuring students have access to adequate and adaptable learning environments, whether in-person, virtual, or a combination. The heart of the matter lies in the freedom of educational options. School choice makes diverse educational opportunities accessible to families, dismantling the notion that quality education is a privilege reserved for the affluent. Every parent deserves the freedom to choose the best path for their child’s education. As it stands, taxpayers fund schools that may not benefit their children. Redirecting these dollars back into the hands of parents creates a system where informed choices determine the efficacy of schools. This fosters competition, improving the educational landscape for teachers and students. And entrepreneurs will have many more opportunities to open new schools not available today in a market dominated by government schools and destructive regulations. Texas must also consider the long-term economic impact of educational choices. The state is cultivating a skilled and adaptable workforce by fostering an environment where students can access tailored educational experiences. This, in turn, attracts businesses and ensures the state remains competitive in an ever-evolving global economy. The Lone Star State stands at a crucial crossroads. Embracing universal school choice is not just a necessity: it is an investment in the future, unlocking the potential of our students and helping every child receive the education they deserve. The time for choice is now. Texas must lead the charge in providing its citizens with the educational freedom they need to thrive in the 21st century or risk getting left behind. Originally published at Dallas Express.

Home “owners” in Dallas and surrounding cities find themselves grappling with the weight of unaffordability as property taxes soar, increasing by $120 million despite the touted cuts at the end of 2023. A recent study reveals the burden on renters in Texas and nationwide, with many paying over 30% of their monthly income on housing. A factor contributing to this rising cost of renting, and housing in general, is soaring property taxes. The predicament stems from excessive state and local spending and purported property tax “cuts” that too often merely shift the burden through exemptions. Renters, technically anyone with a monthly payment or a mortgage since homeowners are just renting from the government, bear the brunt of this financial strain, emphasizing the urgent need for fiscal reform. Late last year, Dallas residents witnessed a modest one-cent property tax reduction rate, with surrounding cities experiencing varying degrees of reduction. Fort Worth saw a 4-cent reduction, and McKinney a 3-cent reduction. Despite these adjustments, most cities, including Dallas, faced increased property taxes eclipsed by rising spending and housing appraisals. Even in Plano, recognized for its low property taxes in the DFW area, homeowners will endure higher monthly property tax amounts due to home valuation hikes. The incongruity between property tax decreases and housing cost increases is alarming, prompting a closer look at the numbers. According to Axios, the average taxable value of homes in Denton County rose from approximately $402,000 in 2022 to around $449,000 in 2023. Similarly, the average market value of Collin County homes increased from about $513,000 in 2022 to roughly $584,000 in 2023. One doesn’t need to be a mathematician to recognize how a property tax decrease of even a few cents doesn’t begin to keep pace with skyrocketing home valuations and rent. No wonder 20% of Dallas homebuyers looked to get out of the city last year. The crux of the issue lies in reining in local spending. The axiom holds: the burden of government is not how much it taxes but how much it spends. Dallas, with its escalating budget that reached a historic high last year, renders proposed property tax cuts inconsequential. My new research released by Texans for Fiscal Responsibility highlights how property taxes continued to go up last year by $165 million, even with the Texas Legislature passing $12.7 billion in new property tax relief. This ended up being the second largest property tax relief in Texas history, not the largest as many politicians have been claiming since last July, which is what I wrote then. The best path for Texans is to finally have their right to own their prosperity instead of renting from the government by paying property taxes forever. This can be done by restraining state and local government spending and using resulting state surpluses to reduce school property tax rates until they’re zero. And by local governments, including Dallas, using their resulting surpluses to reduce their property tax rates until they’re zero. Dallas must adopt a spending limit, one that does not permit the budget to exceed the rate of population growth rate plus inflation – a measure aligned with what the average taxpayer can afford. Performance-based budgeting and independent efficiency audits, preferably conducted by private auditors, should identify opportunities for improvements and reductions in ineffective programs, helping provide more opportunities for property tax relief. Dallas leaders can empower their constituents by redirecting taxpayer money to them while funding limited government. The adoption of these strategic measures not only benefits homeowners but extends its positive impact to renters and business owners, providing tangible rewards for their hard work and fostering a more economically vibrant community. Dallas leaders are responsible for ushering in a new era of fiscal responsibility that ensures affordability for all residents and supports sustained economic growth. The path to long-lasting property tax relief is clear: let’s seize this opportunity for positive change and secure a brighter, more prosperous future for Dallas. Episode 84 is with Dr. Sven Larson, author and economics writer for The European Conservative.

Today, we discuss: 1) Larson's experience growing up in Sweden during its economic collapse and Sweden's example of how big government can destroy the economy; 2) How America's welfare system is beginning to mimic Europe's; and 3) How increased taxes and increased spending decrease GDP growth and opportunities for young workers. Please like and comment on this video, subscribe to the channel, share it on social media, and provide a rating and review. Thanks! Also, subscribe and see show notes for this episode on Substack (www.vanceginn.substack.com) and visit my website for economic insights (www.vanceginn.com). Originally published at American Institute for Economic Research.

Recent headlines for the January jobs report indicate a robust economy. But a more thorough look reveals challenges for Americans. One recent headline proclaimed “Voters are finally noticing that Bidenomics is working.” But just 30 percent of Americans think the economy is doing well. When asked who would handle the economy better, people give former president Donald Trump a 22-point advantage over President Biden. Challenges include increasing part-time employment in recent months, declining household employment in three of the last four months for a net decline of 398,000 job holders, mounting public debt burdens, and declining real wages, which have fallen by 4.4 percent since January 2021. Why these results? Bidenomics is based on costly Keynesian boom-and-bust policies. With so much whiplash, it’s no wonder people are conflicted about the economy. In the latest jobs report for January, a net increase of 353,000 nonfarm jobs from the establishment survey appears robust, as it was well above the consensus estimate of 185,000 new jobs. But let’s dig deeper. Last month, household employment declined by 31,000, contradicting the headlines. The divergence of jobs added between the household survey and the establishment survey has widened since March 2022. This period coincides with declining real gross domestic product in the first and second quarters of 2022 (usually that’s deemed a recession, but it hasn’t been yet). Indexing these two employment levels to 100 in January 2021, they were essentially the same until March 2022, but nonfarm employment was 2.5 percent higher in January 2024. While this divergence mystifies some, a primary reason is how the surveys are conducted. The establishment survey reports the answers from businesses and the household survey from individual citizens. The establishment survey often counts the same person working in multiple jobs, while the household survey counts each person employed. This likely explains much of the divergence, as many people work multiple jobs to make ends meet. The surge in part-time employment and more discouraged workers underscores the fragility of the labor market. Though average weekly earnings increased by 3 percent in January over a year prior, this is below inflation of 3.1 percent. Real average weekly earnings had increased for seven months before falling last month. And there had been declines in year-over-year average weekly earnings for 24 of the prior 25 months before June 2023. These real wages are down 4.4 percent since Biden took office in January 2021. As purchasing power declines, mounting debts become more urgent. Total US household debt has reached unprecedented levels, with credit card debt soaring by 14.5 percent over the last year to a staggering $1.13 trillion in the fourth quarter of 2023. Such substantial growth in debt raises concerns about the current (unsustainable?) consumption trends, business investment, and a looming financial crisis. The surge in mortgage rates to over seven percent for the first time since December and rising home prices exacerbate housing affordability challenges, particularly for aspiring homeowners. An integral component of what some consider the “American Dream,” housing affordability is a major factor discouraging Americans. The euphoria surrounding the January 2024 jobs report is misplaced. Policymakers should heed these warning signs and enact meaningful reforms to address root causes. Biden’s policy approach undergirds most of these difficulties. Bidenomics focuses on his Build Back Better agenda that picks winners and losers by redistributing taxpayer money for supposed economic gains through large deficit spending. We haven’t seen an agenda of this magnitude since LBJ’s Great Society in the 1960s or possibly since FDR’s New Deal in the 1930s. Both were damaging, as the Great Society dramatically expanded the size and scope of government, contributing to the Great Inflation in the 1970s, and the New Deal contributed to a longer and harsher Great Depression. Just since January 2021, Congress passed the following major spending bills upon request of the Biden administration:

These four bills will add nearly $4.3 trillion to the national debt. But at least another $2.5 trillion will be added to the national debt for student loan forgiveness schemes, SNAP expansions, net interest increases, Ukraine funding, PACT Act, and more. In total over the past three years, excessive spending will lead to more than $7 trillion added to the national debt, which now totals $34 trillion — a 21 percent increase since 2021. There seems to be no end to soaring debt with the recent discussions of more taxpayer money to Ukraine, Israel, the border, and the “bipartisan tax deal,” collectively adding at least another $700 billion to the debt over a decade. Record debts accrued by households and by the federal government (paid by households) are not signs of a robust economy. This will likely worsen before it improves, as household savings dry up. And with interest rates likely to stay higher for longer because of persistent inflation, debts will crowd out household finances and the federal budget. The Federal Reserve has monetized much of this increased national debt over the last few years by ballooning its balance sheet from $4 trillion to $9 trillion and back down to a still-bloated $7.6 trillion. This helps explain persistent inflation, massive misallocation of resources, and costly malinvestments across the economy, keeping the economy afloat yet fragile. Excessive deficit spending weighs heavily on future generations, saddling them with unsustainable debt levels they have no voice in. Today, everyone owes about $100,000, and taxpayers owe $165,000, toward the national debt. Of course, these amounts don’t include the hundreds of trillions of dollars in unfunded liabilities for the quickly-going-bankrupt welfare programs of Social Security and Medicare. Future generations will be on the hook for even more national debt if Bidenomics continues and Congress doesn’t reduce government spending now. This is why the national debt is the biggest national crisis for America. We’re robbing current and future generations of their hopes and dreams. Fortunately, there’s a better path forward if politicians have the willpower. This path should be chosen before we reap the major costs of a bigger crisis. I’ve recently outlined what this should look like at AIER. In short, we need a fiscal rule of a spending limit covering the entire budget based on a maximum rate of population growth plus inflation. There should also be a monetary rule that ideally reduces and caps the Fed’s current balance sheet to at least where it was before the lockdowns. My work with Americans for Tax Reform shows that had the federal government used this spending limit over the last 20 years, the debt would have increased by just $700 billion instead of the actual $20.2 trillion. That’s much more manageable and would point us in a more sustainable fiscal and monetary direction. Together, fiscal and monetary rules that rein in government will help reduce the roles that politicians and bureaucrats have in our lives so we can achieve our unique American dreams. If not, we will have wasted many dreams on Bidenomics that can make things look good on the surface, but cause rot underneath. Thank you for listening to the 48th episode of "This Week's Economy."

Please like this video, subscribe to the channel, share it on social media, and provide a rating and review. Also, subscribe and see show notes for this episode on Substack (www.vanceginn.substack.com) and visit my website for economic insights (www.vanceginn.com). Healthcare Costs Are Straining Federal And Household Budgets. Here’s How Biden Can Rein Them In2/14/2024 Originally published at Daily Caller.

Soaring health care spending continues to spiral up, tightening the financial noose on households and government coffers. Families are forced to make difficult choices between paying for essential medical care and meeting basic needs while the federal government struggles to rein in spending amid mounting debt. These soaring health care costs must be addressed with market-based approaches before it’s too late. When the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was passed in 2010, it was heralded as the panacea for reining in healthcare costs. However, the law’s complex regulations and mandates have contributed to administrative bloat and increased overhead costs, ultimately driving up premiums and out-of-pocket patient expenses. Unfortunately, since then, subsequent politicians have failed to correct course. In 2024, federal spending on Medicare, Medicaid, and ACA subsidies will likely exceed the discretionary budget, posing a significant threat to long-term fiscal sustainability. Compulsory spending on health coverage in the private sector infringes upon household earnings. This exacerbates economic challenges for families whose purchasing power is already reduced, as inflation-adjusted average weekly earnings are down 3.1 percent since Jan. 2021. Moreover, the growing burden of health care spending poses a significant threat to long-term fiscal sustainability, as rising debt levels raise concerns about future economic prosperity. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) recently released its annual Budget and Economic Update, painting a grim budget picture. The trajectory is alarming, with expenditures expected to be $6.4 trillion this fiscal year before soaring to a staggering $10.1 trillion by 2034. Also, net interest spending is poised to balloon from $1 trillion to $1.6 trillion by 2034. These projections underscore the urgent need for meaningful reforms to rein in healthcare costs and put the federal budget on a more sustainable path. To address these challenges, policymakers must prioritize fiscal responsibility and adopt measures to remove government as much as possible from healthcare. This would help to quickly get healthcare back to a relationship between a doctor and patient. Today, too many middle layers rob time between the doctor and patient and raise healthcare prices. Policymakers should make market-based reforms. It won’t be done overnight, so there will need to be some steps to get there. It would be great if just making healthcare prices transparent would solve the problem. But the healthcare system is much more dysfunctional than that, unfortunately. Many reimbursement rates are set between doctors and private insurance companies or government programs like Medicaid and Medicare. Those reimbursement rates are so different depending on which entity is negotiating that the prices won’t tell us much, other than how screwed up the system is, but we already know that. A market-based approach should remove obstacles on the demand and supply sides of the market. This should include ending the tax exclusion for employer-sponsored health insurance. There’s a long history of this exclusion, which started during WWII. But while it had good intentions, the result has been a major distortion to the healthcare market. There should also be consideration of a voucher program for Medicare and block grants to states for Medicaid with limited growth each year. These would help reduce the moral hazard and over-subsidization on the demand side. On the supply side, the federal and state governments should remove rules that restrict the supply of doctor offices by removing certificate of need laws. They can also boost the supply of physicians by reducing or eliminating occupational licenses. Unleashing supply and imposing market forces on demand will result in more innovative, affordable, and accessible care for everyone. The resulting reduction in government spending and improved timely access to quality care can help support more prosperity. This would reduce the need for people on government safety net programs. It would also help mitigate higher prices, alleviate strain on household budget burdens, and safeguard the nation’s economic future. These steps will require difficult choices and bipartisan cooperation at the federal and state levels, but the stakes are too high to ignore the issue any longer. Episode 83 is with Dr. Michael Strain, director of Economic Policy Studies and the Arthur F. Burns Scholar in Political Economy at the American Enterprise Institute.

Today, we discuss: 1) Why the American Dream is NOT dead, and much economic pessimism is overblown; 2) The problem with populism and its origins on both sides of the aisle; and 3) Reasons for optimism on wages, GDP, and much more. Please like and comment on this video, subscribe to the channel, share it on social media, and provide a rating and review. Thanks! Also, subscribe and see show notes for this episode on Substack (www.vanceginn.substack.com) and visit my website for economic insights (www.vanceginn.com). Originally published at Econlib.

Amid a heated election year, the teachings of economist Friedrich Hayek provide a guiding beacon, urging us to transcend partisan lines and champion free-market capitalism that benefits everyone. I recently interviewed Dr. Bruce Caldwell of Duke University about his book, Hayek: A Life, 1899-1950, who helped shed light on Hayek’s views on pressing issues today. As we navigate the complex landscape of governance, we should heed Hayek’s call for market-based approaches, especially with trade and immigration, where the clash of political ideologies often obscures the path to rational decision-making. Hayek’s teachings underscore the need for policy approaches prioritizing broader economic health rather than conforming to the whims of political affiliations or interest groups. He did not advocate for simplistic labels like “left and right” but viewed political thought as a triangle, with socialism, conservatism, and liberalism representing the three points. He favored liberalism, in the classical sense. His writings compel us to consider whether policies align with our principles and values. One example is trade protectionism, with tariffs enacted while president and pushed again by Donald Trump. Hayek’s book, The Road to Serfdom, cautioned against the pitfalls of protectionism and advocated for free-market principles that embrace competition in free trade. While protectionist measures like tariffs may appeal to certain political bases, they come at the expense of economic efficiency and growth. They ultimately cost us more for purchases and inhibit our choices as competition is artificially manipulated where it would otherwise organically select the best providers of resources. A Hayekian approach to trade involves understanding that dynamic economies thrive on diversity and exchanging goods and services across borders. Another issue at the forefront of political debates that Hayek’s approach helps shed light on is immigration. He recognized that allowing the free movement of individuals fosters economic dynamism and innovation. Policies that restrict immigration solely for political gain risk stifling economic growth and impeding the exchange of ideas that fuels progress. A Hayekian perspective on immigration advocates for policies that acknowledge the economic benefits of a diverse and dynamic workforce. Instead of succumbing to populist narratives that frame immigration as a threat, Hayek prompts us to view it as an opportunity. An influx of skilled and motivated individuals can contribute to a vibrant economy, filling gaps in the labor market and injecting fresh perspectives that drive entrepreneurship. Too often, misinformation about immigration has led even conservatives to favor more government involvement in tightening borders and deportation. However, as Hayek outlined in his development of “the knowledge problem,” expecting a government of people with limited knowledge of the issue and tradeoffs from policy choices too often results in worse outcomes. The people in government do not and never will have all the answers. Instead, collecting everyone’s ideas in the market leads to having the most available knowledge and, therefore, better outcomes. In short, government failures are worse than any perceived market failures. Taking a cue from Hayek, we should strive for more free trade agreements, especially with our allies, which means an end to all tariffs and other barriers. We should also enact market-based immigration policies that balance national security concerns with the economic advantages of attracting talent from diverse backgrounds. As we prepare to select our nation’s president for the next four years, Hayek’s teachings serve as a guidepost, urging us to prioritize people’s well-being over the allure of party-centric agendas. Embracing a Hayekian perspective requires a willingness to critically evaluate policies based on their economic merit rather than their alignment with partisan ideologies. Only by doing so can we navigate the complex economic landscape and ensure a prosperous and dynamic future for all. Originally published at AIER.

Congress hasn’t done its primary job of passing a balanced budget or even a full-year budget in decades. This must change soon before the fiscal crisis gets worse. But that’s unlikely because few seem to care. Congress recently passed the third continuing resolution for fiscal year 2024 in the amount of $1.7 trillion. This budget legerdemain kicks the federal budget to March, when members will repeat the same omnibus process, one fraught with hijinks and grandstanding. Instead of an actual debate about what we should or should not spend on a department and agency basis, we get calls to “shut down the government” if any number of demands aren’t met. Now, there’s a “bipartisan tax deal” that could add more than $600 billion to the debt over a decade. Democrats don’t seem to care about the debt much, and some who adhere to the ideology of modern monetary theory even think it is helpful for economic growth. But the Republicans also seem to have little, if any, courage to restrain spending, so they just keep cutting taxes and spending us into greater levels of debt. The late, great economist Milton Friedman said, “I am in favor of reducing taxes under any circumstances, for any excuse, with any reason whatsoever because that’s the only way you’re ever going to get effective control over government spending.” But spending is the ultimate burden of government on taxpayers and must be addressed first. The Republican agenda has prioritized border security, rightly or wrongly, over everything else to deal with a humanitarian crisis along the border with Mexico. Former president and top GOP presidential contender Donald Trump has insisted on prioritizing this issue. Events at the border continue to boil with the fight between Texas Governor Greg Abbott and President Biden after a recent Supreme Court decision. The decision has limited reach as it “temporarily allows the Border Patrol agents to continue cutting and moving the razor wire installed by Texas. However, since the ruling came through the emergency docket, the case is now passed back down to the lower court, who will hear the case with oral arguments.” The Republican pursuit of an aggressive border security deal as the number one priority risks further inflating bloated spending as the issue gets subordinated. While some argue that illegal immigration costs far more than border security, compelling studies indicate that immigrants, when provided opportunities, make substantial contributions to society, enriching the economy. The more aggressive approach to border security during Trump’s term contributed to extravagant federal deficit spending. There has also been a high cost to Texans in the state’s budget to address border security issues of more than $5 billion in the current budget and at least $5 billion more since 2016. Addressing illegal immigration issues and averting an impending fiscal crisis requires substantial debate about these issues rather than the current partisan-fueled fire drill over continuing resolution funding. With budget deficits expected to be at least $2 trillion per year over the next decade and net interest payments recently surpassing $1 trillion, every scarce taxpayer dollar must be used wisely, if at all. This could be done with market-based reforms that would foster better fiscal, economic, and border situations. Economist Richard Vedder and others proposed an immigration approach that would create an international market for visas whereby the government issues some of them for refugees, and the rest are auctioned off to people willing and able to purchase them. The government could use this money to pay down deficits, and there would be better accountability for those with visas while providing necessary resources along the border. The biggest national threat continues to be Congress’ profligate spending, which the primary drivers are so-called “entitlements” and must be swiftly reformed with market-based approaches. But right behind it is the Federal Reserve’s bloated balance sheet, which must be addressed. Despite a 14 percent reduction since its peak of about $9 trillion in May 2022, the Fed’s balance sheet remains a staggering 85 percent higher than pre-pandemic levels. Lingering issues of the Fed running losses of $116.4 billion last year, propping up struggling financial institutions with its costly bank term funding program, and the ongoing cost of trying to artificially hold down market interest rates as federal budget deficits soar exacerbate a fiscal-monetary crisis. Manifestations of the underlying economic malaise are evident in falling real wages down 1.3 percent since Biden took office, inflation surpassing set targets, unattainable housing affordability, and families grappling with saving money. These symptoms, rather than isolated issues, indicate the pervasive consequences of unchecked government spending and money printing, casting a long shadow on Americans’ well-being. The latest efforts by Congress to pass the continuing resolution and propose the latest tax deal will make the fiscal situation worse. While the latest idea of a fiscal commission could do what is good in theory, there are already calls to raise taxes, which will be detrimental to the economy and the fiscal picture. The path forward must be fiscal sustainability. This includes a long-term solution of a spending limit. The limit should cover the entire budget and hold any growth to a maximum rate of population growth plus inflation. This growth limit represents the average taxpayer’s ability to pay for spending. Doing so would have resulted in just a $700 billion increase in the debt instead of the actual increase of $20 trillion from 2004 to 2023. The spending limit should be combined with a monetary rule that removes much of the discretion of central bankers. This will support sound money. It can be achieved by moving to a single price stability mandate and preferably a high-powered money growth rate rule of the Fed’s assets. Other rules include the Taylor rule or nominal GDP targeting. While each of these rules has pros and cons, the money growth rate rule advocated for by Milton Friedman is the simplest. It’s simply a rule based on how fast currency plus bank reserves grow. This would be the easiest for the public to understand, to hold officials accountable, and to tie the Fed’s balance sheet directly to inflation. John Taylor proposed what’s been coined the Taylor rule that estimates what the federal funds rate, which is the lending rate between banks, should be based on the natural rate of interest, economic output from its potential, and inflation from target inflation. Scott Sumner most recently popularized nominal GDP targeting, which uses the equation of exchange (MV=Py) to allow the money supply times the velocity of money to equal nominal GDP. There are different variations of it, but the key is that velocity changes over time, so the money supply should change based on money demand to achieve a nominal GDP level or growth rate over time. Rules over discretion, at least until we can rightfully end the Fed, should hold those in Congress and at the Fed in check because their limited knowledge will always result in bad outcomes for people in the marketplace. Such measures are pivotal in preventing further debt accumulation, safeguarding America’s credibility, and preserving the economy’s stability. The choices made today will reverberate into the future, shaping the economic landscape for future generations. This call to action is for policymakers to tread carefully, adopt prudent fiscal and monetary sustainability through a rules-based approach, and prioritize the long-term well-being of the country with market-based reforms over short-term politics. Failure on these issues will prevent us from addressing the humanitarian crisis along the border, China, or other concerns. These efforts will be challenging, but they’re essential for freedom and prosperity. Thank you for listening to the 47th episode of "This Week's Economy."

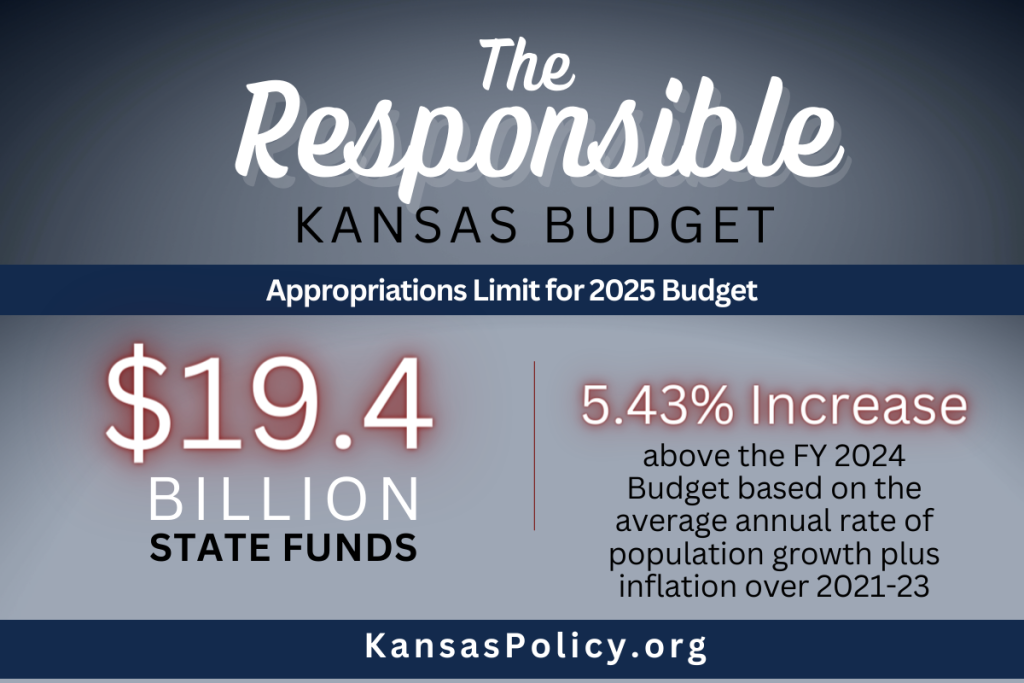

Today, I cover the following and more in 10 minutes: 1) National: - The federal fiscal trajectory is unsustainable and must be corrected before more crises happen, as the trust funds for Social Security and Medicare are expected to run dry over the next decade - U.S. household debt rose by $212 billion in Q4 2023 to a new record of $15.7 trillion - Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell recently noted on 60 Minutes that no target federal funds rate cuts until at least May 2024, and Congress must get control of deficit spending - What’s really going on at the border? I wonder if it has anything to do with Trump’s trade war and lockdowns, as apprehensions started increasing in 2020 before Biden took office 2) States: -Texas approved a new constitutional amendment that provides $10 billion for low-interest loans to companies building thermal energy plants, increasing corporate welfare in Texas -Americans for Tax Reform has updated the Sustainable Budget Project website, showing how states can improve budgets and providing economic and fiscal comparisons -The Kansas Policy Institute released the third iteration of the Responsible Kansas Budget, revealing ample opportunity for Kansas to limit government spending and reduce tax rates. 3) My Media Hits & Other: - I had a blast at the Brickell Unconference in Miami with many freedom fighters known as Freedom Conservatives - Check out this week’s LPP episode with Dr. Bryan Caplan on the myth of the rational voter, the case against education, open borders, and more -Don’t miss this upcoming LPP episode on Monday with Dr. Michael Strain on the national debt crisis, Trumpism, and why the American dream isn’t dead Please like this video, subscribe to the channel, share it on social media, and provide a rating and review. Also, subscribe and see show notes for this episode on Substack (www.vanceginn.substack.com) and visit my website for economic insights (www.vanceginn.com). Podcast: Are Republicans and Democrats Causing America’s Fiscal Crisis? Will the 2024 Election Help?2/5/2024 Episode 82 is with Dr. Bryan Caplan, professor of economics at George Mason University and a New York Times bestselling author.

Today, we discuss: 1) Myth of the rational voter and how politics has become a religion, 2) Reasons why the U.S. is heading toward a fiscal crisis because neither party will restrain spending; and 3) Case against education, school choice pros and cons, selfish reasons for having more kids, and open borders. Please like and comment on this video, subscribe to the channel, share it on social media, and provide a rating and review. Thanks! Also, subscribe and see show notes for this episode on Substack (www.vanceginn.substack.com) and visit my website for economic insights (www.vanceginn.com). Originally published at Kansas Policy Institute. Kansas, like most states, has a spending problem, not a revenue problem. The 2025 Responsible Kansas Budget offers several ways that the state can limit its spending to pave the way for tax reform and economic growth in the future. In June 2023, Kansas ended FY 2023 with collected tax revenues at $10.2 billion – a 4.1% or $402 million increase over the collected tax revenues of FY 2022. According to the Kansas Legislative Research Department, even if Kansas had enacted a flat tax bill during its 2023 legislative session, the state would end FY 2028 with $2.7 billion in its ending balance and $1.8 billion in the Budget Stabilization Fund, totaling $4.5 billion in reserves. At the same time, spending has grown massively over the last decade. According to the FY 2025 Governor’s Budget Report, the approved FY 2024 General Fund budget of $9.918 billion is 13.6% more than the approved 2023 budget. In FY 2020, the State Fund appropriations equaled $12.6 billion, but has ballooned into and after the COVID-19 pandemic to be $19 billion in FY 2023 and a base of $18.4 billion for FY 2024. If Kansas’s annual appropriations had grown at the rate of population growth plus inflation since FY 2005, State Fund appropriations would be $6.4 billion lower in FY 2024 than the actual base appropriations. This equates to a $46.6 billion cumulative difference from FY 2005 to FY 2024. What this number represents is higher taxes on Kansans, slower economic growth, and fewer opportunities for people to flourish. Podcast: Real Average Weekly Earnings Fall AGAIN: Can Americans Keep Up With Costs in 2024?2/2/2024 Thank you for listening to the 46th episode of "This Week's Economy."

Today, I cover the following and more in less than 12 minutes: 1) National: - Average weekly earnings adjusted for CPI or PCE declined in 2022 and 2023 during the Biden administration. - In an X poll, 85% of voters wanted to cut government spending, 10% said to cut taxes, 3% said to raise taxes, and 2% said to raise spending. - Is Oren Cass right to criticize "market fundamentalism”? 2) States: - My research by Texans for Fiscal Responsibility shows how the Legislature’s property tax relief last session was the second largest in state history despite what some have been claiming. - My research on the Responsible Louisiana Budget provides a roadmap to fiscal sustainability in Louisiana. This is needed because employment has declined for 7 straight months, and people keep leaving the state. - My commentary at Complete Colorado calls on Governor Polis to do as he’s promised and reduce tax expenditures so there is more opportunity to cut income taxes, which should include less spending. 3) My Media Hits & Other: - I was quoted in Forbes discussing how Texas could have universal ESAs and save at least $13 billion per year, but too many want to grow the budget. - I was recently accepted to be a 2024 Club for Growth Foundation Fellow. -Don't miss last week's LPP episode with Dr. Bruce Caldwell on Friedrich Hayek, including his upbringing, economics, and much more - Set your alarms for Monday's LPP episode on Monday with Dr. Bryan Caplan on open borders, reasons to have more kids, an end to education, and more. Please like this video, subscribe to the channel, share it on social media, and provide a rating and review. Also, subscribe and see show notes for this episode on Substack (www.vanceginn.substack.com) and visit my website for economic insights (www.vanceginn.com). |

Vance Ginn, Ph.D.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed