|

Originally published at National Review Online.

Few government programs are regularly up for debate as much as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), commonly known as food stamps. The latest controversy is whether the food purchased by its recipients should be restricted to healthier diets that exclude snacks and sodas. While this approach seems reasonable, its tradeoffs necessitate SNAP reforms that balance keeping this costly program temporary for recipients while supporting their agency and choice for long-term self-sufficiency. Enacted in its current form in 1964 as part of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty, SNAP has evolved into one of the nation’s most extensive safety-net programs, assisting more than 42 million Americans at a cost to taxpayers of $113 billion in 2023. With the Farm Bill coming up for reauthorization by Congress on September 30, it’s time to consider improvements for SNAP and other programs in the existing legislation. The Farm Bill has included funding and rules for commodity programs since it was first enacted in the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933. But nutrition (primarily through SNAP) is expected to account for 84 percent of the $1.5 trillion spent on programs in the bill over the next decade. The free-market approach to SNAP reform should be rooted in economic freedom and individual empowerment and emphasize the importance of preserving flexibility in food purchases while promoting self-sufficiency and work for recipients. This perspective draws inspiration from the teachings of free-market economists such as Milton Friedman, who championed the idea of individual choice in economic decision-making. Since its inception, SNAP has undergone numerous reforms and expansions, reflecting shifting societal attitudes and economic realities. Originally conceived as a program to provide recipients quick, temporary relief from hunger and malnutrition, SNAP has become a permanent fixture for many people experiencing economic hardship. For example, a household of four — to be eligible, its gross monthly household income must not exceed $3,250 — will receive a maximum monthly allotment of $973 per month. Central to SNAP reform should be the concept of self-sufficiency. SNAP can honor recipients’ dignity and agency as they navigate their way through the challenges posed by poverty by allowing them to make purchases based on their preferences and circumstances, even if that includes snacks or soda. This flexibility respects recipients’ autonomy and acknowledges their capacity to make informed decisions about their dietary needs. This can also help reduce the incentive for recipients to sell SNAP allotments to others and purchase items they prefer more. We should also acknowledge that these food subsidies distort the grocery market. The restrictions on what SNAP recipients can purchase today drive them to specific items such as milk. The artificial boost in demand then drives up the price and sometimes the profit margins for those items, thereby making them more expensive for everyone while lining the pockets of a few suppliers. Because SNAP raises some prices for Americans and adds to the national debt, contributing to higher interest rates and inflation, we need a better-functioning program or we need to end it. In addition to promoting self-sufficiency, a flexible SNAP program should align with work to reduce poverty so recipients use the program temporarily as intended. Rather than imposing top-down restrictions on food choices, as some are trying to do, policy-makers should focus on unleashing opportunities for recipients to improve their circumstances through education, training, and employment. These steps have a proven record of supporting long-term success. Furthermore, a streamlined approach to SNAP administration would improve the program’s effectiveness while minimizing waste and abuse. By reducing bureaucratic hurdles, we could help ensure that the taxpayer dollars that fund the program are used more efficiently to support those in need. As policy-makers contemplate reforms to SNAP with the upcoming Farm Bill renewal, they must recognize the program’s historical context and evolution. Originally conceived as a temporary measure for recipients to address hunger and malnutrition, SNAP has become a permanent, costly safety net for many recipients. By preserving flexibility in food purchases and empowering recipients with more opportunities to work and move out of poverty, we can support individual freedom and decision-making, two fundamental elements of a vibrant and prosperous society. The Farm Bill presents an opportunity to do so through meaningful reforms to SNAP that help strengthen Americans’ resolve to overcome obstacles. The above reforms would make the help provided by SNAP temporary and flexible, and complement it with a pathway to work. There should also be a push to reduce bureaucratic bloat by streamlining the program and arranging for periodic independent efficiency audits by third-party private firms or a state auditor, so that its funds only go to the people they are intended for. Moreover, adhering to more free-market approaches across the economy — with less government spending, lower taxes, and reduced regulation — can provide more opportunities for people to get jobs and move out of poverty forever. This will allow people to flourish rather than being dependent on government programs that discourage self-sufficiency. As we navigate the complexities of food insecurity, let us heed the wisdom of free-market economics and empower recipients to chart their path to a brighter future.

0 Comments

Episode 73 is with Dr. Gale Pooley, adjunct scholar at The Cato Institute, senior fellow at The Discovery Institute, and co-author of the new book, "Superabundance."

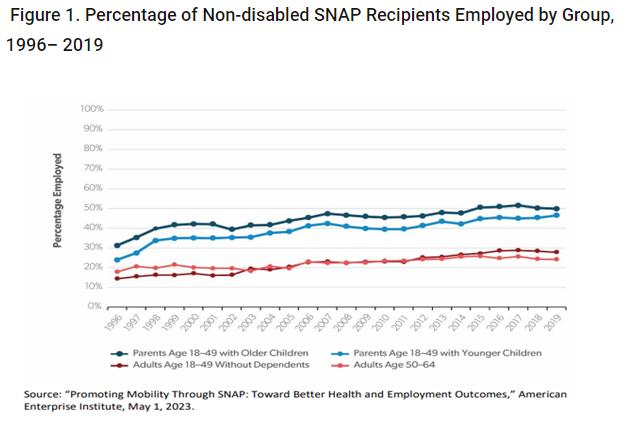

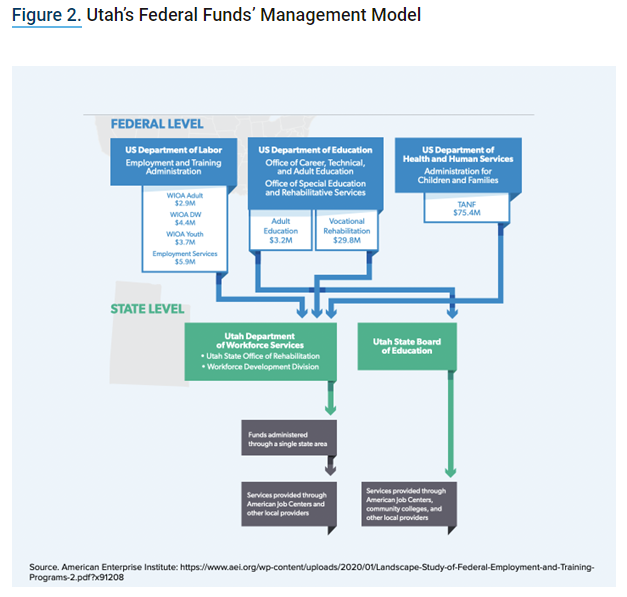

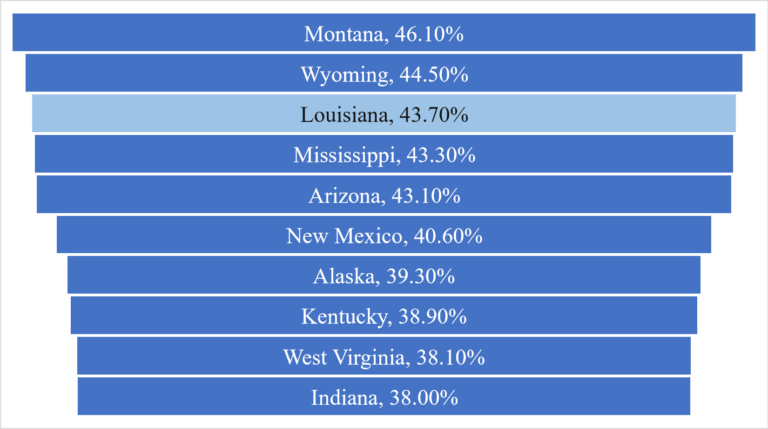

Gale and I discuss the following and more: 1) The state of abundance in America and how we compare to other countries; 2) How government interference through regulations and subsidies are restricting healthcare, education, and entrepreneurs; and 3) Why AI should be embraced, not feared, and money is not our most valuable economic asset. If you found today's discussion valuable, be sure to check out Gale's book: https://www.cato.org/books/superabundance Please like this video, subscribe to the channel, share it on social media, and provide a rating and review. Also, subscribe and see show notes for this episode on Substack (www.vanceginn.substack.com) and visit my website for economic insights (www.vanceginn.com). Louisiana has one of the highest poverty rates out of all the states, but why? That’s a complicated question for which there are several right answers, some of which are more difficult to solve than others. But one contributing factor isn’t so complicated, and it’s something legislators can and should address soon: safety-net program dependance. Research reveals that safety-net programs often trap people in poverty rather than lift them out, and a high percentage of Pelican State residents depend on these programs. Therefore, to promote long-lasting self-sufficiency, and thereby a more prosperous economy, Louisiana must reform its safety-net programs. Louisiana had 17,670 safety-net programs users per 100,000 in 2019, making it the second-most safety-net dependent state in the country behind only New Mexico. Meanwhile, 18% of Louisianans rely on SNAP (food stamps) or approximately 1 in 6 residents compared with 1 in 8 individuals participating in SNAP nationally. While SNAP helps families in the short-term experiencing hardship, the reality is that many participants show that the program doesn’t help them reach long-term independence, but can in fact keep them from it. SNAP contains work disincentives, which explains why its participants have low employment rates. Angela Rachidi, senior fellow and Rowe scholar in poverty studies at American Enterprise Institute, recently reported “that the employment-to-population ratio among work-capable SNAP participants without dependents has hovered between 15 and 30 percent over time. A 2018 report by the Council of Economic Advisors analyzed household survey data and found that a slightly higher share of SNAP participants worked while receiving SNAP, but even their analysis suggested that 50 percent or fewer worked” (see Figure 1). Safety-net programs like SNAP are often referred to as “anti-poverty” programs, since that’s the supposed end goal. But when up to a third of work-capable SNAP recipients remain unemployed over time, the path out of poverty for these participants is not readily apparent. Without incentives and supports that encourage employment and self-sufficiency, users are enabled to stay dependent, and therefore, stuck in poverty. This cycle harms the individual, communities, and thereby, Louisiana. As if the challenges for Louisiana contained within SNAP weren’t bad enough, other safety-net programs compound the problem. The Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), which provides grants to states to purportedly help people get out of poverty, lacks efficacy. A performance audit in Louisiana found that the state does “not collect sufficient outcome information to determine the overall effectiveness of TANF-funded programs and initiatives. The current performance measures that DCFS uses to monitor and evaluate TANF programs are mostly output and process measures which are not useful in determining whether programs are effective at meeting TANF goals.” One of TANF’s official goals is to “end the dependance of needy parents on government benefits through work, job preparation, and marriage.” Considering that Louisianans on TANF have the rate for those participating in the labor force in the nation, at just 3.5% in the fiscal year 2020, it hardly seems that TANF is accomplishing its goal. Work is integral to human dignity and staying out of poverty; addressing the work participation rate will lead to more productive and happy people and, thereby, a better state economy as residents are equipped and eager to contribute to society. This starts with better-managing safety net programs like SNAP and TANF while connecting participants with work. Louisiana can draw valuable lessons from Utah’s effective implementation of a “no wrong door” strategy for streamlining government programs. In the 1990s, Utah successfully integrated various safety-net programs, such as employment services, vocational rehabilitation, and TANF, resulting in simplified eligibility requirements, a unified application process, and the assignment of dedicated case managers to guide individuals through the system. Utah improved the quality of services and enhanced administrative efficiencies, and achieved cost savings through this approach. These reforms equipped individuals to get their needed help and become self-sufficient. Louisiana must strive to empower its work-capable population, enabling them to pursue opportunities for growth and flourishing within the state. With a streamlined and effective system like Utah’s, Louisiana can transition from safety-net programs to employment, reducing poverty and fostering prosperity.

That’s part of the Pelican Institute’s “Comeback Agenda” for Louisiana. The time is now. Originally published at Pelican Institute. Today, I'm honored to be joined by Leslie Ford, adjunct fellow at the American Enterprise Institute’s Center on Opportunity and Social Mobility and a senior fellow with the Alliance for Opportunity. We discuss: 1) The history of the war on poverty, how safety net programs have evolved, and where the war on poverty stands today; 2) How safety net programs can discourage upward mobility and keep people trapped in poverty through penalties such as those on marriage; and 3) Data on what requirements help safety net recipients achieve long-lasting self-sufficiency and prosperity, and more. You can watch this interview on YouTube or listen to it on Apple Podcast, Spotify, Google Podcast, or Anchor. Please share on social media, subscribe to your favorite platform and my newsletter, like it, and leave a 5-star rating.

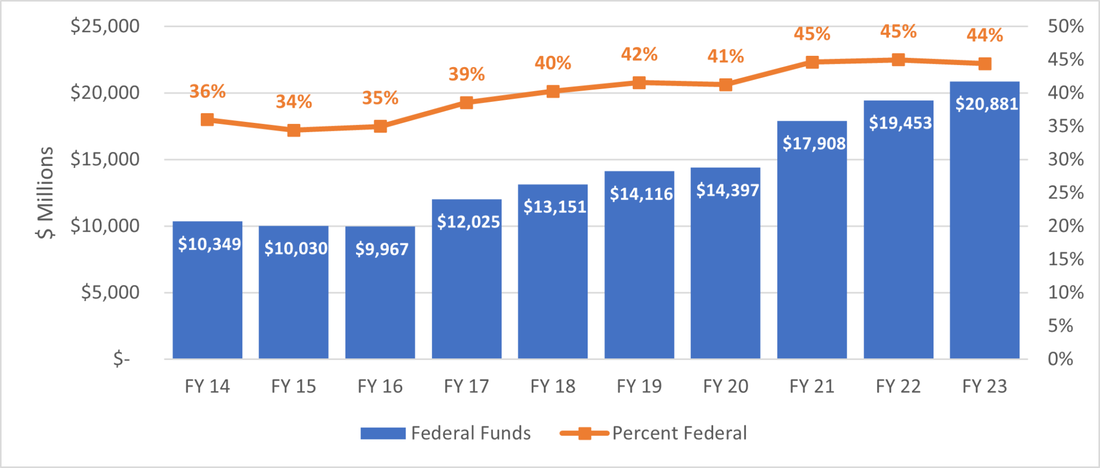

Find show notes, thoughtful economic insights, media interviews, speeches, blog posts, research, and more at my website and here in my Substack newsletter. Please subscribe to this newsletter, share it with your friends and family, and leave me a comment. Louisiana’s state government is the third most dependent state on federal funding. This is according to a report recently released by WalletHub that shows state rankings, with Alaska and Wyoming coming in at first and second. This follows another report release by the Tax Foundation that also ranks Louisiana as the third most dependent on federal funds, with only Montana and Wyoming ahead. This trend doesn’t appear to be getting any better. In 2014, federal funding comprised just 36% of the state’s total budget, whereas today, that percentage rises to 44%. The substantial increase in Louisiana’s use of federal funds from 2016 to 2017 is primarily due to Medicaid expansion. This program expanded the number of individuals eligible to receive Medicaid, and therefore increased the amount of money in the state’s general fund needed to match the additional federal funding. The match rate ranges from 30% to 40% per year based on personal income in the state. Disaster-related recovery has also contributed to the increased use of federal funds. Beginning in 2020 and 2021, Congress sent a large amount of federal funds due mostly to the COVID-19 pandemic response. There were also two major hurricanes, Laura and Ida, and numerous smaller hurricanes that also occurred in those fiscal years, which prompted an additional influx of federal funding from FEMA, HUD, and other agencies. Every program that is either partially or fully funded by the federal government comes with restrictions on its use – the “strings attached.” The substantial increase in Louisiana’s use of federal funds from 2016 to 2017 is primarily due to Medicaid expansion. This program expanded the number of individuals eligible to receive Medicaid, and therefore increased the amount of money in the state’s general fund needed to match the additional federal funding. The match rate ranges from 30% to 40% per year based on personal income in the state. Disaster-related recovery has also contributed to the increased use of federal funds. Beginning in 2020 and 2021, Congress sent a large amount of federal funds due mostly to the COVID-19 pandemic response. There were also two major hurricanes, Laura and Ida, and numerous smaller hurricanes that also occurred in those fiscal years, which prompted an additional influx of federal funding from FEMA, HUD, and other agencies Every program that is either partially or fully funded by the federal government comes with restrictions on its use – the “strings attached.” Most of the federal funding is used for social safety-net programs. Louisiana has the highest poverty rate in the nation, with nearly 20% of the population in poverty and even more on at least one safety-net program. State and local spending on these programs create an annual burden of nearly $3,000 per person.

To reduce the state’s dependence on federal funds for large line-items such as social safety net programs, the state must empower more individuals to realize their own self-sufficiency and ability to flourish. Work must once again become a priority. WalletHub’s report also compared states using their gross domestic product, or GDP, per capita compared to the amount of federal funds flowing into each state. Louisiana is placed in the “high dependency, low GDP” category, with a GDP ranking of 40th in the nation. Louisiana’s economy is not growing as fast as the rest of the country. With the highest poverty rate in the country, lawmakers need to pursue reforms that will make the state more economically competitive and increase opportunity for all Louisianans. Research has shown that more responsible state budgeting and spending, tax relief, and removing barriers for employers to start businesses and workers to work help reduce the number of people in poverty and reduce the dependency on the federal government by individuals and the state. According to WalletHub and the Tax Foundation, Utah is one of the least dependent states on federal funding. This is because the state reformed its social safety-net system decades ago, linking assistance with employment opportunities. This made Utah the state with the fastest economic and job recovery post pandemic. Louisiana should take a page out of Utah’s playbook and achieve the same. It’s time to reduce the state’s and individuals’ dependence on Congress and the national debt, which exceeds $31 trillion and is shared by all states including our own. And it’s time to get Louisiana off the top of another bad list and into a comeback story that we know is achievable. Originally published at Pelican Institute. The push to ditch reliable energy is out of control. Politicians are manipulating the energy market through subsidies, tax breaks, and environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG) initiatives in regulations and government pensions.

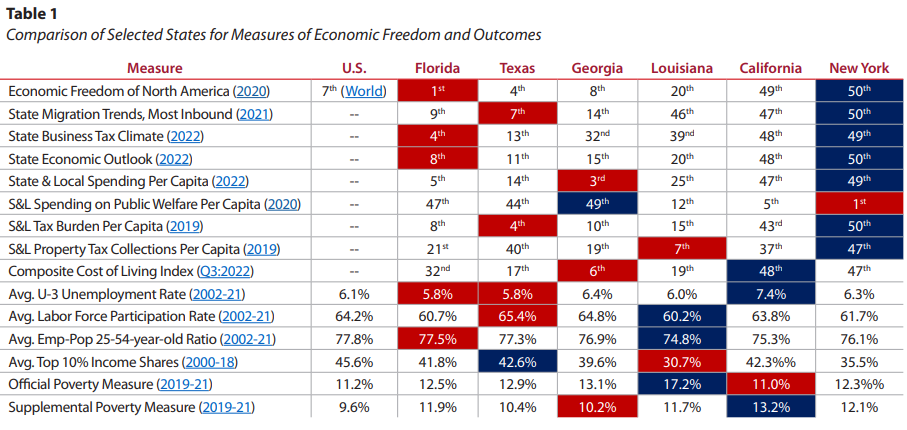

It’s also concerning that the “big three” investment institutions, which collectively hold over $20 trillion in assets, too often coerce the companies in which they have significant investments to bend the knee to their big-government political ideology, such as complying with the Paris Climate Accord. Sadly, the result of this virtue signaling to prop up unreliable wind and solar comes at high costs for little benefits—if any benefits at all. And more than hemorrhaged taxpayer dollars are at stake: this green energy agenda increases poverty. It must stop. While the media is constantly ringing alarm bells about the always-changing climate, not enough people are alarmed by the economic trade-offs these unreliable green energy initiatives create. But that requires an honest comparison of the climate change risks versus the economic costs, both of which impact future generations. The International Energy Agency (IEA) finds that there were an expected 20 million more people without electricity globally, totaling 775 million people, in 2022. Many of these people are in sub-Saharan Africa, who are facing increasing hardship due to rising costs for food, fuel and other necessities. This situation is made worse by the left’s insistence on unreliable sources of energy that have forced many Europeans to use wood for stoves and heat instead of much cleaner-burning natural gas. Forcing some of the population to depend on energy sources that don’t work ultimately pushes them into hardship and poverty when those methods fail. Texas experienced this problem in a tragic way two years ago during its historic weather event of freezing temperatures and accumulations of ice and snow that left thousands without power, contributing to an estimated 246 deaths. Such a tragedy should never have happened in America’s energy capital, but these are gambles that politicians take when offering subsidies to unreliable variable energy providers that make it difficult for reliable thermal energy to compete, even though thermal energy is the most stable and reliable form. Fortunately, Texas let a property tax break for businesses called Chapter 313 expire in December 2022. That tax break was often used by renewable energy companies to lower their tax bills (and operating costs). Still, some already want to bring Chapter 313 or something like it back. This should be a non-starter. That’s not to say that climate change couldn’t have consequences, but considering the projected minimal benefits from expensive initiatives by politicians and the need for adaptation, the trade-offs seem hardly worth it. And this says nothing of the benefits of more CO2, which is necessary for life on earth. More broadly, if every signatory of the Paris Accord, including India and China, decarbonized by 2050, the temperature differentiation by 2100 would be just 0.17 degrees. And according to climate change activists, the cost to get there could be as much as $21 trillion through 2050. Businesses attempting to go green would be forced to raise their prices significantly to make a profit, a normally tough task that’s only made harder by present-day sky-high inflation. But if subsidies and other artificial means of skewing the energy market continue, then businesses that don’t receive subsidies and can’t afford to “go green” simply won’t be able to compete. This would result in a massive reallocation of resources that will contribute to less economic growth, more poverty, and less energy stability. Not only can over-dependence on unreliables lead to hardship, but it often counteracts the green energy innovation it wants to spur. One of the reasons the U.S. is so prosperous is that it is the most responsible and efficient at producing and utilizing energy, having reduced criteria pollutants 78% in the last 50 years. And what has supported this is our wealth acquired via free-market capitalism. That’s why the best thing for activists and politicians seeking improved adaptation to climate change is to get out of the way and let the free markets, meaning free people, work. Subsidies, tax breaks, ESG initiatives, and other hindrances to a well-functioning market process should be abandoned. When politicians push funds into green energy agendas, often to win votes through virtue signaling, precious scarce taxpayer resources are wasted. Markets work, but we have to let them. Individuals and entities should be left alone when choosing which energy sources to direct their funds and business. Otherwise, the outcome is less prosperity and more poverty. There is a better way. Originally posted at Real Clear Energy. Those states that practice more free-market capitalism with limited government tend to have better economic performance, providing an economy and civil society with opportunities to help the neediest among us achieve long-lasting prosperity. Key points – Comparing institutional frameworks in states and their outcomes provides key factors that encourage thriving states, families, and entrepreneurs. – Measures of economic freedom and government burden are useful indicators of which states have growing economies and more jobs over time. – The results for these states demonstrate how institutions that encourage individual liberty, free enterprise, and civil society support prosperous outcomes, particularly in relieving poverty. – States ought to pursue policies that advance more of these lessons to provide a robust economy and flourishing civil society that will best help the neediest among us. Original post at TPPF. Frankie Johnson, a college-educated single mother from Washington, D.C., moved to Atlanta to distance herself and daughter from an abusive husband. Without a job or place to live, she sought government assistance for childcare and transitional housing. While she waited for this assistance, she was offered a job paying $70,000.

She turned it down. Why? Because as much as Frankie needed work, she didn’t want to lose the benefits of housing and childcare when she took the job. Too often government safety-net programs don’t lift people out of poverty for long because they provide specific resources without growth opportunities or flexibility for recipients. In many cases, individuals struggle without the dignity and stable income of work and the cost of “benefit cliffs,” whereby recipients lose more in assistance than they do in income gained from work, due to varying income thresholds across existing safety-net programs. Unfortunately, Frankie’s story is all too common. Many people choose to keep the guaranteed payments from taxpayers over the uncertainty of working and losing those payments. But this tradeoff isn’t the only problem with the current safety-net system. Safety-net recipients often lack the financial literacy necessary to get out—and stay out—of poverty. Additionally, while many recipients are enrolled in multiple safety-net programs, each program is managed separately, burdening the taxpayer with costly administrative costs. And for a recipient, it can seem like a full-time job keeping up with the paperwork to remain enrolled. Making matters worse, too many people in poverty, and working families, are struggling from the highest inflation in 40 years. And the handouts of taxpayer funds by the federal government over the last two years artificially drove up savings and kept people not working longer than necessary thereby changing the calculus of whether to work or stay on safety nets. This is evident in the latest U.S. jobs report for August 2022 which showed that the reported unemployment rate rose slightly to 3.7%, which remains low, but it’s actually much higher as the labor-force participation rate remains well below the pandemic-related shutdowns in 2020. Considering the same pre-shutdown labor-force participation rate, America’s labor force is missing approximately three million workers. Many aren’t looking for work because of generous handouts contributing to the labor shortage problem and reducing their gains from the dignity of work. With these challenges in the labor market and the effects that the current recession will have on people over time, we must improve our safety-net system for recipients and taxpayers alike. Americans have already spent about $25 trillion (adjusted for inflation) on more than 80 federal safety-net programs since 1965. While there have been some successes in helping people out of poverty, there is a need for a more effective program that doesn’t just give people fish but teaches them to fish. This is what our new, holistic approach called empowerment accounts (EAs) would do. EAs would condense and replace overstretched, wasteful safety-net programs (excluding Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid, for now) into one consolidated, effective program with funding provided monthly via a debit card tied to a financial app and time-limited to a maximum of one year. To qualify, people would work at least part-time while meeting regularly with a community navigator. The program also helps teach the Success Sequence, whereby 97% of people aren’t in poverty if they graduate high school, get a full-time job, and marry before having kids. And savings are incentivized by the recipient being able to keep extra funds after the limited program period, which will help to reduce the benefits cliff. By helping reduce bureaucratic bloat and streamlining payments to recipients instead of waste and other programs, EA recipients would have more flexibility to spend the money on approved items across the current safety-net items and foster financial independence. When implemented, EAs will provide a crucial 21st century reform to our troubled safety-net system and help rein in governmental budgets as people have less need for safety nets because they find a well-paid job and ways to provide for their families. The improvements to recipients using EAs—incentivizing financial literacy, finding dignity through work, building social capital, and mitigating benefits cliffs—will help Frankie Johnson and others achieve long-term self-sufficiency. Originally posted at TPPF Current safety-net programs too often discourage recipients from achieving long-term self-sufficiency, but a new holistic approach called empowerment accounts would help recipients achieve this with existing resources. Key points

Also find at TPPF website. When did it all start to go wrong? In the early 20th Century, Americans fighting poverty not only lost sight of the goal—lifting families up—but even of the problem itself, and instead sought to remake society through government intervention, often at the expense of the very people they were meant to help.

In 1920, Owen Lovejoy, president of the National Conference of Social Work, set a “new task” for the increasing number of social workers—they would become “social engineers,” who would create “a divine order on earth as it is in heaven.” As Marvin Olasky writes in his book, “Renewing American Compassion,” such a goal is far too lofty for individual acts of charity; “As some leaders forgot that compassion means suffering with, they looked more and more to government. They combined power seeking (for the good of others, of course) with social universalistic faith.” Who has time to worry about that man under the bridge when we’re remaking the world? This helps to explain failures in the war on poverty. Even setting aside the Great Depression and World War II, our most concentrated efforts have failed to move the needle on the official poverty rate. Nationally, about $25 trillion (adjusted for inflation) have been spent to combat poverty since 1964 when President Lyndon B. Johnson’s “war on poverty” engendered the Great Society. And the nation spends about $1 trillion per year on more than 80 federal safety-net programs. However, the country’s official poverty rate was declining before 1964, which was the primary measure available, but remained virtually unchanged between 10-15% since then, suggesting a failure of these redistributionist measures to substantially mitigate poverty. In addition to losing sight of the goal, we’ve lost sight of the problem itself—poverty. We haven’t done a good job of defining it, much less fixing it. To define the official poverty measure, the U.S. Census Bureau provides an estimated income threshold annually. When a family’s income falls below that threshold, they are considered to be in poverty, which the rate was 11.4% in 2020. There are flaws with this measure. So, if we merely look at it, we know a lot less about real poverty than we might think we do. While there are now better measures of poverty based on broader income levels or consumption, which tend to show much lower rates of poverty since 1964, these measures are focused primarily on material things rather than other important issues that influence poverty. What can we know about other issues related to poverty? We can look at statistical correlations and learn a lot. The strongest correlation we see with poverty is a job. Employment, in general, drives down poverty, irrespective of wages, although the effect is more pronounced with higher wages. The availability of jobs has a significant impact on poverty in both the present and a decade into the future. Education matters, as those with a high school diploma have a 24.7% poverty rate. Graduating high school is vital to help stay out of poverty. Demographics also matter. Perhaps the most powerful demographic structure, and the most powerful predictor of poverty in general, is single motherhood (25.6% poverty rate overall or 46.2% for those with children under 6 years old). Single motherhood is also a strong predictor of intergenerational poverty. Location matters; for example, there are 41 Texas counties within 100 miles of the U.S.-Mexican border that have been considered “persistently poor,” meaning at least 20% of the residents have been living in poverty for the last 40 years. Age is also a factor in poverty, but its impact varies depending on other group characteristics. Metro areas with a younger Black population have higher poverty rates, while areas with an older Black population have lower poverty rates. What does this tell us? It tells us where we can focus our efforts—and it’s not a one-size-fits-all approach. The path forward must consider these facts for increased opportunities for people to find financial self-sufficiency through a more holistic approach to poverty relief through an education, job, training, community, social capital, intact families with a mother and father, and other avenues provided by civil society whereby government provisions are available as a last resort. This follows much of what’s in the success sequence which is a formula of at least graduating high school, working full-time, and marrying before having kids (in that order) to have a 97% chance of not being in poverty. By connecting people to work, education, or training, enhancing community-based case management, streamlining safety-net programs, and getting resources to those who need it most, we can provide more opportunities for people to be self-sufficient. https://www.texaspolicy.com/too-big-to-succeed-righting-the-wrongs-in-the-fight-against-poverty/  Did you know there’s a state park in Arkansas where you can search for diamonds—real diamonds? And you get to keep what you find. In April, Adam Hardin was visiting Crater of Diamonds State Park and came across a 2.38 carat stone—the largest found so far this year. Diamonds can be found in the 37-acre plowed field, but naturally, they’re rare. It’s a little like the successes that can be seen in our nearly 60-year-old War on Poverty: valuable, but rare. Nationally, about $25 trillion (adjusted for inflation) have been spent to combat poverty since 1964 when President Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty engendered the Great Society. However, the country’s poverty rate was declining before 1964 but remained virtually unchanged since then, suggesting a failure of these redistributionist measures. But over the years, we’ve learned much. And we know what works in combatting poverty. We also know which key institutions and factors contribute to keeping people in poverty. With good policy—and clearer objectives—we can reverse this trend and truly lift people out of debilitating circumstances that lead to generational poverty. But first, a little history. The 1920–21 recession was the last major economic downturn in American history that was not met with federal intervention designed to stabilize the economy and mitigate poverty. A decade later, Presidents Herbert Hoover and Franklin Delano Roosevelt presided over the first large-scale and nationwide anti-poverty measures during the 1930s and the Great Depression. Despite these large-scale interventions, the unemployment rate remained in double digits for the remainder of the 1930s. More people were dependent on new government programs, and the costly economic effects of these and other government actions reduced both productivity and job creation. A quarter century later, President Lyndon B. Johnson advocated his War on Poverty as part of domestic policy initiatives commonly called the Great Society. But again, poverty relief programs did not substantially accelerate the poverty rate’s reduction—in fact, the rate of decline slowed before essentially stalling. Why? Because these efforts failed to address the real drivers of poverty—in many instances, they became drivers of poverty themselves. There are several factors that are strongly linked with continued poverty and an inability to build income and wealth. The most powerful predictor of poverty in general is single motherhood. Another factor is where you live (including all 41 Texas counties within 100 miles of the U.S.-Mexican border, considered “persistently poor”). And age is also a factor in poverty, but its impact varies depending on other group characteristics. Metro areas with a younger Black population have higher poverty rates, while areas with an older Black population have lower poverty rates. But possibly the most pertinent factor in keeping people trapped in poverty is an incentive not to work or to be more productive. For example, a “benefits cliff” occurs when a safety-net recipient goes back to work, increases their workload, or accepts a higher rate of pay, resulting in increased total earned income—which then triggers a greater loss of payments from government programs. What works? Work. Employment, in general, drives down poverty. By connecting people to work, education, or training, enhancing community-based case management, streamlining safety-net programs, and getting resources to those who need it most, we can create more opportunities for people to be self-sufficient—and thereby reduce the number of Americans experiencing poverty—so long as we have the will, perseverance, and right approach. Finding diamonds in a field of dirt isn’t easy; nor is providing people with a real path out of poverty. But with diligence, and a keen eye, we can see more and more success. https://www.texaspolicy.com/we-know-what-works-in-the-war-on-poverty/  Poverty is often misunderstood because most people do not know who qualifies as poor, how much governmental assistance is available to the poor, or what allows people to escape poverty. Understanding this is crucial to provide more opportunities for work-capable people to attain self-sufficiency with a flourishing civil society as a first resort and effective government programs as a last. Key points • Poverty has long been a public policy concern with roughly $25 trillion (adjusted for inflation) spent on it by governments in the U.S. just since the 1960s’ Great Society in an attempt to help people move out of poverty • But this sort of primary financial assistance by governments has not substantially mitigated poverty and too often made it worse through dependency on government programs. • Instead, there should be a more holistic approach to effectively mitigate poverty through work, community, and opportunity to provide people with long-term self-sufficiency. • Texas and the U.S. can do this with a flourishing civil society and a robust economy as a first resort and effective government programs as a last resort instead of spending more on the current flawed approach.  In recent years, there’s been a growing consensus that the “Success Sequence” is a key pathway to avoiding poverty. Unfortunately, this prevailing theory doesn’t fully account for circumstances beyond one’s control. We need a more holistic approach to poverty prevention and alleviation. Brookings Institution fellows Ron Haskins and Isabel Sawhill originally coined the “Success Sequence” in their book, Creating an Opportunity Society. The sequence notes that if you finish high school, get a full-time job, and marry before kids (in that order), you’re more likely to avoid poverty. However, while research finds a strong correlation between this sequence and avoiding poverty (97% of Millennials), proof of causation has been more elusive, leaving gaps in how to achieve lasting poverty relief. The Success Sequence doesn’t account for adverse situations beyond one’s control, such as the diminishing value of a high school diploma, availability of full-time jobs, accessibility to the workforce by the formerly incarcerated, and affordability of housing. Today, one might do everything “right” and still experience poverty. Ultimately, the path to long-term poverty relief includes—but is not limited to—the Success Sequence. To maximize opportunities for success, policies should remove obstacles often imposed by governments. This includes ensuring abundant job opportunities, addressing workforce and affordability issues, and streamlining safety nets. Doing so would allow safety nets to fulfill their purpose as a trampoline to quickly spring people back into self-sufficiency rather than as a hammock that traps recipients into a cycle of dependency on government. Recently, the Texas Public Policy Foundation launched the Alliance for Opportunity initiative with our friends at the Georgia Center for Opportunity and the Pelican Institute in Louisiana. This initiative promotes a strategic policy roadmap for these states that in many ways supplements the Success Sequence. It does so by working to keep vulnerable Americans on track, ensure everyone has a right to earn a living, and address poverty through the justice system. One way is to reform education systems so that career and technical education funding is individualized and institutional funding is tied to employment and wage outcomes. Doing so will ensure students are better prepared for today’s jobs. Consider the return-value funding model for the Texas State Technical College, a two-year institution with an emphasis on technical programs geared toward post-graduation employment. They partner with businesses, government agencies, and other education institutions to coordinate career development routes for students. Notably, the Texas Legislature established an outcomes-based funding model for TSTC based on the annual wages of its graduates five years after graduation. Legislators across the country should utilize similar competency-based models to improve employment outcomes. Policymakers should also be looking for ways to reduce or to remove burdensome occupational licensing requirements and encourage paid apprenticeships throughout the education system in order to protect the right to work and maximize the skills for in-demand jobs. Occupational licensing overall has been shown to restrict the labor market, presenting a significant cost of entry to work, even as there is limited evidence that licenses increase the quality of goods, services, or public safety. States should instead look to implement a systematic process of identifying and removing overburdensome licensing regulations through processes such as a sunset review, while expanding universal recognition of licenses obtained in other states with similar requirements. Moreover, lawmakers should align education and workforce programs to ensure students are able to learn and earn wages as they work. By improving the availability of paid apprenticeships, states can maximize opportunities to find meaningful education and employment. The State of Georgia’s program recently had more than 60% of youth apprentices receive a full-time job offer from their employer upon completion. Finally, for those workers who lose a job unexpectedly, as 22 million Americans did during the government-imposed shutdowns due to the COVID-19 pandemic, legislators should reduce disincentives to work by revamping and streamlining safety net programs. One of the most common reasons recipients are discouraged from pursuing better employment outcomes is the “benefits cliff.” Because of the setup of safety-net programs, many recipients find that a small increase in earnings will result in a large loss of benefits. This creates a vicious cycle of dependency and despair. States must flatten these “cliffs” by leveraging their flexibility with block grant programs and waivers in federal law while keeping the programs tied to work, training, or education, such as an empowerment accounts pilot program. The Success Sequence is a noble, beneficial approach to help avoid poverty, but ultimately its application has gaps that should not be taken for granted. With the Alliance’s strategic policy roadmap, we hope to provide an improved situation with more opportunities in a flourishing civil society that helps those in need achieve financial self-sufficiency, dignity, and purpose faster and longer. https://www.texaspolicy.com/supplementing-the-success-sequence/  We think about poverty all wrong. And because we think about poverty all wrong, much of our approach to alleviating it is wrong. Thus, poverty stubbornly persists and the trillions of dollars we spend barely nudges the needle to long-term poverty relief. The problem is the disconnect between what poverty really is and what our public policies are trying to solve. A clear understanding of poverty is offered by Steve Corbett and Brian Fikkert in their book, When Helping Hurts. “While poor people mention having a lack of material things, they tend to describe their condition in far more psychological and social terms…” the authors explain. “Poor people typically talk in terms of shame, inferiority, powerlessness, humiliation, fear, hopelessness, depression, social isolation and voicelessness. Low-income people daily face a struggle to survive that creates feelings of helplessness, anxiety, suffocation and separation that are simply unparalleled in the lives of the rest of humanity.” Most Americans don’t define their self-worth based on material possessions (or lack thereof). But our public policies too often focus on stuff. American families below the poverty line have access to a plethora of programs, benefits, cash, and services that provide them with things, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic. But what they lack is a voice. Alleviating poverty means increasing opportunities to gain human dignity, purpose, and self-sufficiency. Understanding that poverty encompasses more than just a dearth of disposable income is key to addressing the systemic issues at play. Those suffering from real poverty live a very different life and see their condition as something quite different from simply being “broke.” It’s more appropriate to say they lack the social capital—a buzz phrase, sure, but a useful one in this case—upon which to rely. The poor lack many intangible things most of us take for granted, like having marketable skills and using them to contribute to our communities in a way society values. Absent a sense of their own dignity, purpose, and self-sufficiency, people are left with dependency to survive—a poison to the human soul. Any attempt to alleviate long-term poverty with little more than repeated handouts, without also connecting people with work, training, or education and building community connections, is not helping, it’s hurting. If we truly intend to love our neighbor as God has commanded, we must recognize that the War on Poverty, fought LBJ-style with government programs, has been lost. A new approach must be charted—an approach that emphasizes keeping vulnerable Americans on track, developing valuable skills, individualizing plans that help people overcome their specific barriers to employment, and—most importantly—an exit strategy. With few exceptions, the goal should be to help people earn self-sufficiency through increased opportunity and work, not lock them into a lifetime of dependency and despair. A good example of this approach is Bonton Farms, an inner-city Dallas urban farm that provides support for people to bridge the gap from poverty and prison and has helped hundreds of people gain a new sense of dignity and purpose. At Bonton Farms, it’s not about handouts. “This gives a lot of guys the opportunity to change,” one former inmate says. “If they want to do better, they can. If they want to be more than just a street guy, a drug dealer, they can. If they want their kids to watch them be something more, it’s possible. That’s what we show them.” Work is the key. Work means using one’s God-given talents and learned skills to provide a value to the community. Doing so confers on those suffering from poverty the very things they cry out for, such as hope, purpose, and a voice. They gain agency—the ability to make their own decisions—and learn skills necessary for them and their families to prosper. A job is the beginning of an exit strategy out of poverty. This should be a bipartisan issue. Indeed, some of the greatest gains made in recent decades fighting poverty came via the Welfare Reform Act of 1996, passed by Republican majorities in the House and Senate and signed by Democrat President Bill Clinton. But even that was incomplete, and later presidents and governors dropped many of the work requirements that were its centerpiece. These factors contributed to the recent launch of a multi-state poverty relief initiative called the Alliance for Opportunity. This includes three state-based think tanks, the Georgia Center for Opportunity, Pelican Institute in Louisiana, and Texas Public Policy Foundation. With a top-notch team and high-quality work that provides a toolkit for policymakers, we hope to help 1 million people out of poverty in these three states to show proof of what works for other states and for Congress to hopefully follow. Our new efforts must begin with a full and fair assessment of how the current situation is helping keep vulnerable Americans on track. Existing programs, especially at the state levels, must be audited and made more transparent by improving data collection to evaluate desired outcomes. And we must partner with community groups closest to those in need—the real safety nets—while streamlining current programs with new ideas like empowerment accounts. Additionally, we must remove barriers to ensure everyone has the right to earn a living. This includes removing obstacles like unreasonable occupational licensing, delay of a driver’s license for many who were formerly incarcerated, or simply instituting more apprenticeship programs to improve access to skills training. And last, but certainly not least, we must address poverty through criminal justice reforms, which our new initiative aims to do. This includes restoration through diversion programs and specialty courts, life and work skills through rehabilitation and transition programs, and a productive path back into the community for the formerly incarcerated. We must do more than send a check every month like the child tax credit payments sent by Congress in the second half of 2021. We must treat the poor like human beings, not just a number. We must meet them where they are and help them achieve their full potential. If poverty was as simple as a lack of funds, then surely the money spent thus far would have made a bigger dent. But it’s not that simple. It never was. We’ve merely sought too long for easy answers. Now it’s time to roll up our sleeves and pursue a new path to eliminate dependency and restore the dignity of work so that more people can be financially self-sufficient. https://www.texaspolicy.com/a-new-approach-to-reducing-poverty/ |

Vance Ginn, Ph.D.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed