|

1 Comment

Did The Supreme Court Just Give The CFPB Too Much Power - Radio Interview on Lars Larson Show5/22/2024 Originally published at Daily Caller.

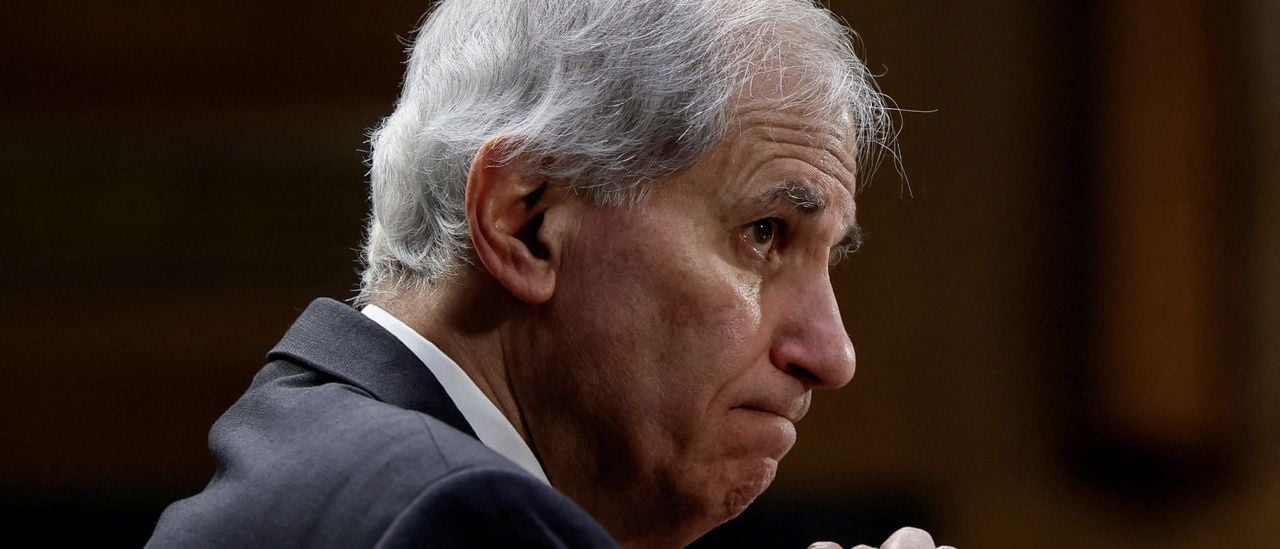

The Biden administration’s heavy regulation of America’s banking industry hinders economic growth and raises consumer costs. As FDIC Chair Martin Gruenberg faces scrutiny over the agency’s toxic workplace culture, lawmakers have a prime opportunity to address the broader issue of overregulation. Instead of focusing solely on internal misconduct, Congress should seize this moment to reduce the oppressive regulatory framework burdening financial institutions and the economy. The current banking regulatory environment is burdensome and counterproductive. Tens of thousands of pages of rules and guidance dictate banking operations and are treated as legally binding by U.S. regulators. Multiple agencies, including the Federal Reserve, FDIC, OCC, and CFPB often overlap and contradict each other, leading to confusion and inefficiency. This excessive regulation is an administrative burden and a significant barrier to economic prosperity. The Biden administration’s regulatory overreach is evident in the extensive presence of government examiners within banks. These examiners enforce ad hoc mandates that effectively dictate business decisions, and failure to comply can result in secret, unappealable ratings downgrades. This system creates a chilling effect, stifling innovation and growth. The annual stress tests conducted by the Federal Reserve impose the highest bank capital requirements globally. However, these tests rely on opaque models and unrealistic scenarios and are never subjected to public scrutiny. This significantly impacts how banks operate and adds to the regulatory burden. The lack of transparency undermines the credibility of regulatory agencies and results in unnecessary costs for banks, which are often passed along to consumers. Furthermore, the politicization of agencies such as the CFPB, FDIC, and OCC exacerbates the problem. These agencies increasingly pursue regulatory agendas through public relations stunts and policy announcements from the White House rather than through transparent processes. The predominantly progressive leanings of regulatory staff further bias outcomes against the banking industry, contributing to an environment in which financial institutions are unfairly targeted and overburdened with compliance costs. The economic consequences of this regulatory overreach are profound. As compliance costs soar, assets are migrating away from traditional banks, despite banks having access to deposits and being able to provide low-cost credit. This mainly affects community, mid-sized, and regional banks, which struggle with the high compliance costs of holding a banking charter. For all banks, high capital requirements and intense supervision increase the cost of lending, significantly impacting small businesses and low- to moderate-income individuals. This limits access to credit and slows economic growth. Reducing these excessive regulations would lead to significant gains in economic activity, highlighting the substantial benefits of reducing overregulation. The Biden administration’s excessively complex regulations, oppressive oversight, and politicized agenda stifle innovation, raise consumer costs, and hinder economic growth. Given these glaring issues, Congress should streamline regulations, increase transparency by requiring regulatory agencies to publish their models and scenarios for public comment, and ensure regulatory agencies operate independently of political influence. This would provide regulatory relief for community, mid-sized, and regional banks to enhance competition and access to credit. By reining these excesses in, Congress can unshackle the economy and promote a more competitive, dynamic financial sector that benefits all Americans. The potential rewards — a more prosperous, innovative, and dynamic America — make this a fight worth undertaking. |

Vance Ginn, Ph.D.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed