|

Originally published at Kansas Policy Institute.

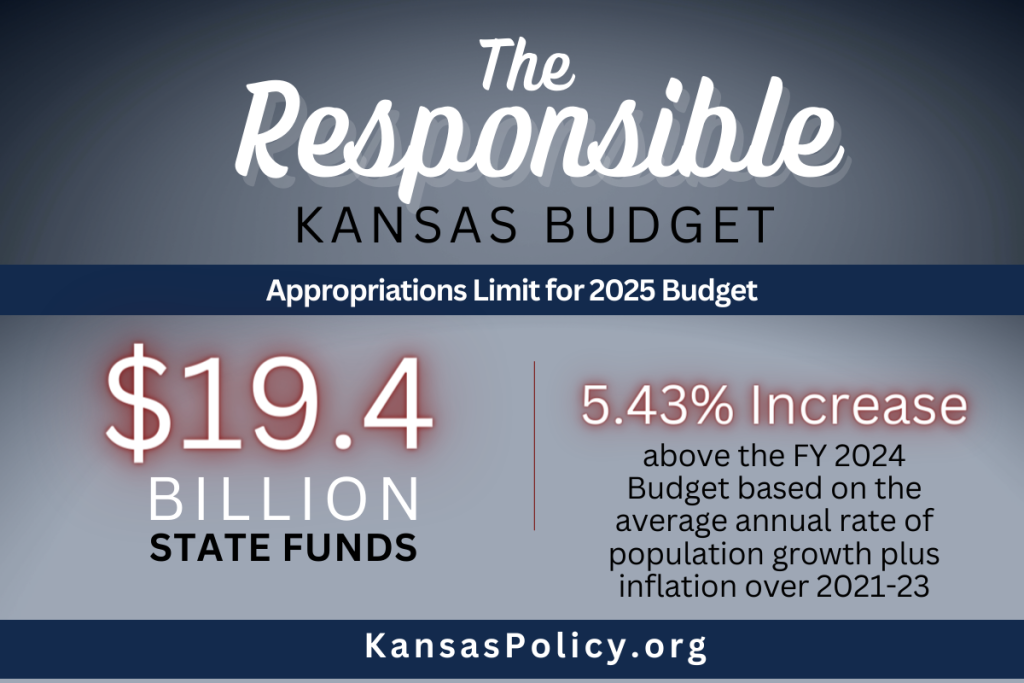

Kansas has been simmering in economic stagnation for decades, trailing behind national averages in job growth, population increases, and economic growth. Like a poorly tended grill, high taxes and selective business subsidies have smoked out potential growth, leaving stagnation rather than sustenance. From 1979 to 2022, Kansas’s private job growth was just 53% compared to the national average of 88%. Imagine the vibrancy of having an additional 451,000 jobs in the state—jobs that could have been fostered with more competitive tax policies. Kansas has seen a net exodus of nearly 198,000 residents since 2000, driven away by an unwelcome tax environment. The states with the lowest tax burdens saw an influx of 4.6 million people from domestic migration during the same period, while the high-tax states watched 10.7 million residents pack up and leave. According to recent IRS data, Kansas lost $2.1 billion in adjusted gross income due to people moving elsewhere since 2017. The Kansas Policy Institute’s Green Book shows per capita spending of $4,941 in 2022 was substantially higher than in states with no personal income taxes ($3,283) and the ten best economic performance ($3,543). States with lower tax burdens have had better job growth and economic activity. Between 1998 and 2022, the ten states with the lowest state and local tax burdens averaged 51% growth in private-sector employment versus 34% for the ten states with the highest burdens. Kansas, ranked 44th during this period, achieved just 16% growth. Furthermore, Kansas’s high spending per person translates to higher taxes, ultimately burdening its citizens and hampering economic growth. More recently, Kansas’s unemployment rate ticked up to 2.9% in May 2024, a slight increase but a revealing one. The total nonfarm payroll employment saw a marginal uptick by 100 jobs. Beneath this weak report, there was more weakness as the private sector lost 300 jobs while the government added 400 jobs. This isn’t growth; it’s a reshuffle at a high cost to private-sector workers. Over the past year, Kansas has seen an overall increase of 24,000 jobs, with the private sector contributing 18,700 and the government sector adding 5,300, or about 20% of the total. During the recent special session, the Legislature passed several measures to boost the state’s economic prospects. One notable legislative action was passing a multi-billion dollar STAR bond to attract major sports franchises, especially the Chiefs and Royals from Missouri, just a few miles away. Investing in sports is like predicting Kansas weather—unpredictable and always exciting. There is potential for economic rain, but this will likely put you in a financial storm instead. Moreover, the recent special session saw efforts to provide broad tax relief, with the key being reducing tax brackets from three to two, which is a correct step toward a flat income tax. These changes could significantly impact Kansas’s economic landscape, reducing the tax burden and potentially helping grow the economy. However, the effectiveness of these measures will depend heavily on their implementation and the accompanying fiscal restraint. Flattening the income tax would transform Kansas from a flyover state into a destination. This move would simplify the tax code, making it fairer and less of a headache—because the only thing Kansans should worry about rising are the sunflowers. Kansas has also flirted with property tax relief with KPI promoting a constitutional amendment to limit appraisal valuation increases, which has broad support. The same or separate constitutional amendments should limit property tax levies, which cover the product of appraisals and tax rates, and cap state and local government spending to the rate of population growth plus inflation. The latter would best limit the true burden of government in the form of spending, providing predictability and stability for homeowners and businesses alike. Kansas is sitting on a $4 billion reserve—it’s like having a savings account when you’re deep in credit card debt. Responsible budgeting ensures fiscal sustainability and prevents the state from falling into the cycles of budget shortfalls and hasty tax hikes that have plagued it in the past. By following this approach, over-collected taxpayer money called a “surplus,” can be returned by cutting a flat income tax rate. This can be achieved by spending on essential services outlined in the state’s constitution, providing opportunities for strategic budget cuts and growth of no more than the rate of population growth plus inflation. This balanced approach helps ensure fiscal sustainability without compromising essential services. By implementing bold tax reforms and adopting a disciplined approach to spending, Kansas can pave the way for a prosperous future. These measures will create an environment conducive to job creation and economic competitiveness, ensuring that Kansas becomes a place where businesses thrive, and residents enjoy a higher quality of life.

0 Comments

Originally published at National Review Online.

States must restrain spending growth while cutting and flattening income-tax rates. Economist Milton Friedman famously said, “I am in favor of cutting taxes under any circumstances and for any excuse, for any reason, whenever it’s possible. The reason I am is because I believe the big problem is not taxes, the big problem is spending.” This sentiment encapsulates the driving force behind the tax-cut revolution transforming the American economic landscape. This movement toward lower, flatter, and, in some cases, no income taxes is reshaping state fiscal policies to relieve taxpayers from funding excessive government. For instance, Georgia’s reduction of the state income-tax rate from 5.49 percent to 5.39 percent and Idaho’s shift to a flat income-tax rate of 5.8 percent enhance competitiveness and support more economic activity. Iowa’s adoption of a flat income tax rate of 3.8 percent, one of the lowest in the nation, further exemplifies this trend. Arkansas reduced individual and corporate tax rates, providing tax relief for the third time in 15 months. Hawaii’s substantial increase in standard deductions and adjustment of tax brackets aims to provide relief to low- and middle-income families. Kansas included property-tax relief alongside consolidating its income tax from three to two brackets. The tax-cut revolution represents a shift towards more efficient and equitable tax systems. By adopting flatter, lower tax rates, states can enhance their economic competitiveness and improve the quality of life for their residents. However, these tax cuts must be accompanied by sustainable budgeting practices that limit government spending. In 2023, Americans for Tax Reform (ATR) launched The Sustainable Budget Project, which monitors state government spending and tracks which states have or have not enacted sustainable budgets. The project defines a sustainable budget as one that limits the pace of state government spending to lower than the rate of population growth plus inflation. This approach ensures that government growth is kept in check, preventing excessive taxation and debt accumulation. Examining spending trends from 2014 to 2023 reveals the crux of the problem. Aggregate 50-state spending, excluding funding from taxpayers through the federal government, increased by 59.1 percent during this period. If states had restrained their spending to the rate of population growth plus inflation, they would have spent $1.44 trillion in 2023, $430 billion less than the $1.87 trillion spent. Over the entire decade, this would have saved $1.4 trillion, leaving more money in taxpayers’ pockets. Some states have demonstrated the benefits of sustainable budgeting. ATR found that six states held total spending growth below population growth plus inflation: Alaska, Colorado, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Texas, and Wyoming. Additionally, six other states held growth in state funds, which excludes federal funds, below the rate of population growth plus inflation: Louisiana, Massachusetts, Montana, North Carolina, Ohio, and Rhode Island. Sustainable budgeting is the key to ensuring long-term prosperity. By focusing on responsible budgeting and reducing obstacles to economic growth, such as high spending, taxes, and regulations, states can create an environment where everyone can prosper. Improve Immigration by Strengthening American Values with Dr. Veronique de Rugy| LPP ep. 1026/25/2024 Join me for Episode 102 of the Let People Prosper Show to hear a deep discussion with the fantastic Dr. Veronique (Vero) de Rugy, the George Gibbs Chair in Political Economy and Senior Research Fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, who migrated from France to America.

We Explore: -How the entrepreneurial spirit contributes to immigration between countries. - What the differences are between national conservatism and classical liberalism. - Which policies would improve the economic and fiscal picture. Like, subscribe, and share the Let People Prosper Show, and visit vanceginn.substack.com and vanceginn.com for more insights from me, my research, and ways to invite me on your show, give a speech, and more. Hello everyone,

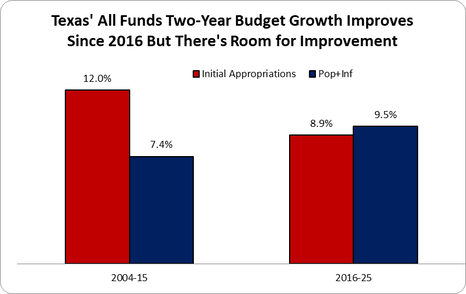

It’s a pleasure to be with you today. As one who believes strongly in free markets and individual liberty and has served as the chief economist of multiple think tanks and at the White House’s Office of Management and Budget, I’ve come from Texas not with barbecue, as you also have delicious barbecue, but with a recipe for economic prosperity that I hope you’ll find equally savory. It’s great to visit Kansas and contribute to the fantastic work at the Kansas Policy Institute. My business at Ginn Economic Consulting works with KPI and 14 other think tanks nationwide. In these capacities, I hear of the attention that Kansas receives for its past tax cuts without spending restraint and current efforts for tax relief. Kansas has been in an economic slow cook for decades, trailing behind national averages in job growth, population increases, and economic output. Much like a poorly tended grill, high taxes, and selective business subsidies have smoked out potential growth, leaving behind more stagnation than sustenance. Let’s chew over some numbers: From 1979 to 2022, Kansas's job growth limped along at just 53% compared to the national average of 88%. Imagine the vibrancy of having an additional 451,000 jobs in the state—jobs that could have been fostered with more competitive tax policies. Moreover, Kansas has seen a net exodus of nearly 198,000 residents since 2000, driven away by a tax environment as welcoming as a blizzard in May. The states with the lowest tax burdens saw an influx of 4.6 million people from domestic migration during the same period, while the high-tax states watched 10.7 million residents pack up and leave. In the most recent IRS data, Kansas lost $2.1 billion in adjusted gross income due to people moving out since 2017. In May 2024, Kansas's unemployment rate ticked up to 2.9%, a slight increase from 2.8% but a revealing one. The total nonfarm payroll employment saw a marginal uptick by 100 jobs last month. Beneath this weak report, there was more weakness as the private sector lost 300 jobs while the government added 400 jobs. This isn’t job growth; it’s a reshuffle at a high cost to private-sector workers. And this is a trend we've seen before. Over the past year, Kansas has seen an overall increase of 24,000 jobs, with the private sector contributing 18,700 and the government sector adding 5,300, or about 20% of the total. Milton Friedman once quipped, “If you put the federal government in charge of the Sahara Desert, in five years there’d be a shortage of sand.” In Kansas, if you continue to rely on excessive taxing and spending for growth, you will find yourself short on more than just jobs and people but on opportunity that drives prosperity. During the recent special session, the Legislature passed several measures to attempt to boost the state’s economic prospects. One notable legislative action was passing a $3 billion STAR bond to attract major sports franchises. Investing in sports is like predicting Kansas weather—unpredictable and always exciting. There is potential for economic rain, but you might be in a financial storm without careful budgeting and rigorous oversight. While what is seen is the possible construction, new jobs around, and new tax revenue, the unseen is costly. This includes the poor precedence for other wasteful acts by the government, higher taxes on those nearby and over time, and the lack of knowledge about what will happen over the next 30 years to the teams, the community, or other costs that come with government planning. Moreover, the recent special session saw positive efforts for broad tax relief, with the key being reducing income tax brackets from three to two, which is a step toward a much-needed flat income tax. Starting in tax year 2024, married Kansans filing jointly would have their taxable income taxed at 5.2% up to $46,000 and at 5.58% above that amount. The changes should significantly impact Kansas by reducing the tax burden and unleashing economic growth as people are incentivized to save, invest, and work. However, the effectiveness of these measures will depend heavily on accompanying spending restraint. Let’s talk about property taxes. Kansas has started the pit on property tax relief, but it’s time to cook it. Tentative tax relief discussions this year hinted at significant cuts, but Kansas should solidify this with a constitutional amendment to limit levy increases. Think of it as putting a leash on a dog prone to running off—you ensure it’s safe and always in sight. The amendment should cap annual increases as low as possible if property taxes increase at all, providing predictability and stability for homeowners and businesses alike. Regarding income taxes, flattening the income tax would turn Kansas from a flyover state into a destination. This move would simplify the tax code, making it fairer and less of a headache—because the only thing Kansans should worry about rising are the sunflowers. While the Legislature tried it this year, you should keep this as part of the approach next time. The reason why is easy to see. States with lower tax burdens consistently show superior economic growth trends; between 1998 and 2022, the ten states with the lowest tax burdens averaged 51% growth in private-sector employment, compared to 34% for the states with the highest burdens. Kansas managed a modest 16% growth during this period, ranking 44th. Kansas is sitting on a $4 billion reserve—it's like having a savings account when you’re deep in credit card debt. You should use this wisely with a responsible budget model that KPI has put forward for years now, allowing spending to grow no more than by population growth plus inflation, preferably by much less to overcome past spending excesses. This isn’t just tightening the belt; it’s ensuring you can still afford it in the future. Responsible budgeting ensures fiscal sustainability and prevents the state from falling into the cycles of budget shortfalls and hasty tax hikes that have plagued Kansas in the past. By following this approach, over-collected taxpayer money, called a “surplus,” can be returned by cutting a flat income tax rate to zero as quickly as possible. Kansas has seen its share of financial missteps, but now is the time for bold action. The legislative decisions made today will determine the state’s economic future. Legislative candidates, you are positioned to lead Kansas into a new era of fiscal responsibility and economic growth. The decisions made in the coming years will determine whether Kansas continues along the path of stagnation or redirects toward prosperity. Consider these policy recommendations not just as suggestions but as necessary steps toward securing a thriving economic future for Kansas. Kansas must also embrace responsible budgeting for these tax cuts to be sustainable. The state should learn from the lesson of excessive spending during the last decade’s troubles, which led to deficits and foolish tax hikes. In fact, the 2025 General Fund budget is 69% higher than in 2017 when Governor Kelly took office, or $3.7 billion higher than inflation over this period. Reining in this excessive use of taxpayer money to spend it on only limited roles outlined in the state’s constitution would provide opportunities for strategic budget cuts and increases of less than the rate of population growth plus inflation. This responsible approach helps ensure fiscal sustainability without compromising essential services. Thank you for your dedication to Kansas and your commitment to principles that enhance not just the economy but also liberty. You can help ensure Kansas becomes a beacon of fiscal responsibility and economic success, where every resident wants to stay and others are eager to join. Roll up your sleeves, sharpen your pencils, and get to work on policies that let Kansans prosper. After all, as Friedman would say, "Nothing is so permanent as a temporary government program"—aim for long-term policies with fewer tradeoffs to support the most opportunities. Thank you, and if you’d like to continue this conversation, I invite you to connect with me at [email protected] and subscribe to my newsletter at www.vanceginn.substack.com. Let’s work together along with the great folks at KPI to create a future where Kansans can truly prosper. Government Spending Is The Problem The late, great economist Milton Friedman said, "The real problem is government spending." This is true as spending comes before taxes or regulations. In fact, if people didn't form a government or politicians didn’t create new programs, then there would be no need for government spending and no need for taxes. And if there was no government spending nor taxes to fund spending then there would be no one to create or enforce regulations. While this might sound like a utopian paradise, which I agree, there are essential limited roles for governments outlined in constitutions and laws. Of course, most governments are doing much more than providing limited roles that preserve life, liberty, and property. This is why I have long been working diligently for more than a decade to get a strong fiscal rule of a spending limit enacted by federal, state, and local governments promptly under my calling to "let people prosper," as effectively limiting government supports more liberty and therefore more opportunities to flourish. Fortunately, there have been multiple state think tanks that have championed this sound budgeting approach through what they've called either the Responsible, Conservative, or Sustainable State Budget. I recently worked with Americans for Tax Reform to publish the Sustainable Budget Project, which provides spending comparisons and other valuable information for every state. This groundbreaking approach was outlined recently in my co-authored op-ed with Grover Norquest of ATR in the Wall Street Journal. When Did This Budget Approach Begin? I started this approach in 2013 with my former colleagues at the Texas Public Policy Foundation with work on the Conservative Texas Budget. The approach is a fiscal rule based on an appropriations limit that covers as much of the budget as possible, ideally the entire budget, with a maximum amount based on the rate of population growth plus inflation and a supermajority (two-thirds) vote to exceed it. A version of this approach was started in Colorado in 1992 with their taxpayer's bill of rights (TABOR), which was championed by key folks like Dr. Barry Poulson and others. (picture below is from a road sign in Texas) Why Population Growth Plus Inflation? While there are many measures to use for a spending growth limit, the rate of population growth plus inflation provides the best reasonable measure of the average taxpayer's ability to pay for government spending without excessively crowding out their productive activities. It is important to look at this from the taxpayer’s perspective rather than the appropriator’s view given taxpayers fund every dollar that appropriators redistribute from the private sector. Population growth plus inflation is also a stable metric reducing uncertainty for taxpayers (and appropriators) and essentially freezes inflation-adjusted per capita government spending over time. The research in this space is clear that the best fiscal rule is a spending limit using the rate of population growth plus inflation, not gross state product, personal income, or other growth rates. In fact, population growth plus inflation typically grows slower than these other rates so that more money stays in the productive private sector where it belongs. To get technical for a moment, personal income growth and gross state product growth are essentially population growth plus inflation plus productivity growth. There's no reasonable consideration that government is more productive over time, so that term would be zero leaving population growth plus inflation. And if you consider the productivity growth in the private sector, then more money should be in that sector at the margin for the greatest rate of return, leaving just population growth plus inflation. Population growth plus inflation becomes the best measure to use no matter how you look at it. Given the high inflation rate more recently, it is wise to use the average growth rate of population growth plus inflation over a number of years to smooth out the increased volatility (ATR's Sustainable Budget Project uses the average rate over the three years prior to a session year). And this rate of population growth plus inflation should be a ceiling and not a target as governments should be appropriating less than this limit. Ideally, governments should freeze or cut government spending at all levels of government to provide more room for tax relief, less regulation, and more money in taxpayers' pockets. Overview of Conservative Texas Budget Approach Figure 1 shows how the growth in Texas’ biennial budget was cut by one-fourth after the creation of the Conservative Texas Budget in 2014 that first influenced the 2015 Legislature when crafting the 2016-17 budget along with changes in the state’s governor (Gov. Greg Abbott), lieutenant governor (Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick), and some legislators. The 8.9% average growth rate of appropriations since then was below the 9.5% biennial average rate of population growth plus inflation since then, which this was drive substantially higher after the latest 2024-25 budget that is well above this key metric (before this biennial budget the growth rate was 5.2% compared with 9.4% in the rate of population growth plus inflation). This approach was mostly put into state law in Texas in 2021 with Senate Bill 1336, as the state already has a spending limit in the constitution. The bill improved the limit to cover all general revenue ("consolidated general revenue") or 55% of the total budget rather than just 45% previously, base the growth limit on the rate of population growth times inflation instead of personal income growth, and raise the vote from a simple majority to three-fifths of both chambers to exceed it instead of a simple majority. There are improvements that should be made to this recent statutory spending limit change in Texas, such as adding it to the constitution and improving the growth rate to population growth plus inflation instead of population growth times inflation calculated by (1+pop)*(1+inf). But this limit is now one of the strongest in the nation as historically the gold standard for a spending limit of the Colorado's Taxpayer Bill of Rights (TABOR) has been watered down over the years by their courts and legislators, as it currently covers just 43% of the budget instead of the original 67%. My Work On The Federal Budget In The White House From June 2019 to May 2020, I took a hiatus from state policy work to serve Americans as the associate director for economic policy ("chief economist") at the White House's Office of Management and Budget. There I learned much about the federal budget, the appropriations process, and the economic assumptions which are used to provide the upcoming 10-year budget projections. In the President's FY 2021 budget, we found $4.6 trillion in fiscal savings and I was able to include the need for a fiscal rule which rarely happens (pic of President Trump's last budget). Sustainable Budget Work With Other States and ATR When I returned to the Texas Public Policy Foundation in May 2020, as I wanted to get back to a place with some sense of freedom during the COVID-19 pandemic and to be closer to family, I started an effort to work on this sound budgeting approach with other state think tanks. This contributed to me working with many fantastic people who are trying to restrain government spending in their states and the federal levels. Here are the latest data on the federal and state budgets as part of ATR's Sustainable Budget Project. From 2014 to 2023, the following happened: Federal spending increased by 81.7%, nearly four times faster than the 23.1% increase in the rate of population growth plus inflation.

Result: American taxpayers could have been spared more than $2.5 trillion in taxes and debt just in 2023 if federal and state governments had grown no faster than the rate of population growth plus inflation during the previous decade. And this would be even more if we considered the cumulative savings over the period. My hope is that if we can get enough state think tanks to promote this budgeting approach, get this approach put into constitutions and statutes, and use it to limit local government spending as well, there will be plenty of momentum to provide sustainable, substantial tax relief and eventually impose a fiscal rule of a spending limit on the federal budget. This is an uphill battle but I believe it is necessary to preserve liberty and provide more opportunities to let people prosper. Sustainable State Budget Revolution Across The Country Below are the states and think tanks which I'm working with and this revolution is going, which you can find an overview of this budgeting approach in Louisiana and should be applied elsewhere. I update these periodically, successful versus not successful budgeting attempts being 20-7 so far.

If you're interested in doing this in your state, please reach out to me. For more details, check out these write-ups on this issue by Grover Norquist and I at WSJ, Dan Mitchell at International Liberty, and The Economist. Originally published at Mackinac Center.

Michigan’s economic and fiscal future hinges on adopting sustainable budgeting practices. Insights from other states show the tangible benefits of fiscal restraint, efficiency, and lower taxes. By examining how other states have managed their budgets, Michigan can learn valuable lessons in improving its fiscal health and thus secure a prosperous future. In 2023, Americans for Tax Reform launched its Sustainable Budget Project. This project monitors state government spending and tracks which states have enacted “sustainable budgets.” The Sustainable Budget Project defines a sustainable budget as one that grows no more than a specific rate: the inflation rate plus population growth, as expressed as a percentage. This project is similar to Mackinac Center’s Sustainable Michigan Budget. For comparison, Texas has focused on fiscal discipline and low taxes, creating a business-friendly environment that attracts investment. It has kept government spending in check, which fosters an environment conducive to economic growth. As a result, it projects a $21 billion surplus next year despite the recent large budget increase. In contrast, California faces a significant economic challenge due to high taxes and heavy spending habits. With the state facing an upcoming budget deficit of at least $45 billion, Gov. Gavin Newsom has proposed painful spending cuts to various social programs. This development highlights the risks of unsustainable budgeting. California relies on volatile revenue sources (especially a progressive income tax with high rates) and has failed to implement spending discipline, leaving it in a precarious fiscal situation. Other states, such as Alaska, Colorado, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Texas and Wyoming have kept spending growth below the rate of population growth plus inflation over the last decade. They’ve maintained lower taxes and enjoyed better economic health even though most of these depend partially on volatile oil and gas activity. These states have demonstrated that sustainable budgeting can lead to greater economic stability and improved quality of life for residents. Their commitment to fiscal discipline has allowed them to weather economic downturns more effectively and avoid severe budget shortfalls. Implications for Michigan Michigan's budget growth outpaces both inflation and population growth, placing a heavy burden on taxpayers. Officials can reduce this burden by adopting sustainable budgeting practices like those of successful states. This will support more economic growth and attract businesses. Sustainable budgeting can also enhance Michigan’s economic resilience, making it less susceptible to economic shocks and fiscal crises, which have historically burdened oil and gas states. The benefits of sustainable budgeting extend beyond fiscal stability. By reducing unnecessary spending and lowering taxes, Michigan can increase disposable income for families, encourage consumer spending, and boost total economic activity. This can lead to more jobs, higher wages and improved living standards for all Michiganders. To achieve sustainable budgeting, Michigan should implement strict budgetary controls, such as spending caps and mandatory budget reviews. Additionally, the state should focus on long-term fiscal and economic health by eliminating wasteful spending, increasing spending prudently and reducing tax burdens. Transparency and accountability in the budget process are also crucial for spending taxpayer money wisely. Sustainable budgeting is not just about balancing the budget — it's about ensuring a brighter future for all Michiganders. By adopting best practices from other states, Michigan can become a model of fiscal discipline and economic vitality, providing a stable and prosperous environment for its residents and future generations. It's a pleasure to speak with the Texas Aggregates and Concrete Association again and enjoy the great resort here with my wife and three young kids. While aggregates and concrete may not always be in the spotlight, they are the bedrock of our infrastructure, forming the foundation upon which we build our homes, businesses, and communities.

Reflecting on my journey, I realize how essential the right direction and strong institutions are in shaping our paths. Much like the solid foundation of concrete, institutions give us the stability to build and grow. Like the economy, my life has been a series of peaks and troughs. In my younger years, I grew up in a low-income, single-mother household in South Houston as my dad had epilepsy, and they divorced when I was five years old. I went to private school from K-2 grades, public school from 3-6 grades, and home school from 7-12. Unlike many of you, I took many risks during my teenage years and began playing drums in a band called "Sindrome," living the rockstar life. But a near-fatal car accident in 2002 was my wake-up call, one of several but the one that turned me toward a brighter path. Through this experience, a month in bed with many bumps and bruises, and a lot of prayer, I found my purpose: to help others through my calling to let people prosper. We find ourselves at a pivotal point in our country and in Texas. The recent elections tell us that there is a clear call for change in the Lone Star State. The upcoming November elections will be another opportunity for the country to steer towards a path of prosperity or continue down a troubling road. As an optimist, I believe in our potential, but I also recognize our country and state's many economic, political, and cultural issues. Policy Uncertainty and Economic Volatility At the national level, we face several economic challenges. The Biden administration has been keen on infrastructure spending, which includes the $1.2 trillion Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. While this aims to rejuvenate our infrastructure, it also raises concerns about efficiency and the role of government in these projects, and the fact that we are running deficits higher than that per year with the national debt at nearly $35 trillion and net interest payments of $1 trillion exceeding national defense expenditures of about $860 billion. Excessive government spending, increased regulation, and interventionist policies often lead to inefficiencies and distortions in the market. Milton Friedman, my favorite economist, warned about the dangers of heavy government involvement, advocating instead for free-market solutions that empower individuals and businesses. Election years heighten policy uncertainty, which can drive economic volatility. Businesses and investors become cautious, waiting to see which policies will prevail. This hesitation can slow economic activity, affecting everything from job creation to investment in new projects. For the aggregates and concrete industry, this means potential delays in infrastructure projects and fluctuations in demand. Milton Friedman once said, "If you put the federal government in charge of the Sahara Desert, in five years, there’d be a shortage of sand." This sharp but insightful remark underscores the inefficiency that often accompanies government intervention. In his view, infrastructure projects should be managed by private entities with a direct stake in the outcome and can respond more agilely to changes and needs. Here in Texas, we are not immune to these challenges. Our state is known for its robust economy and low taxes, but we're grappling with excessive government spending and high property taxes. The Texas Comptroller's report highlights how our spending on transportation is around $10 billion annually. While infrastructure is crucial, we must be mindful of how these funds are used to ensure they generate real value for taxpayers. Weak Labor Market Amid Headlines of Strength Despite headlines showing strength, the U.S. labor market reveals underlying weaknesses. Nearly half of Americans think we are in a recession, reflecting a disconnect between reported statistics and personal experiences. Real average weekly earnings have declined by nearly 4% since January 2021, squeezing household budgets and diminishing purchasing power. The labor force participation rate remains low at 62.5%, significantly below the February 2020 level. If participation were the same as it was then, the unemployment rate would be closer to 6% rather than the reported 4% today. Texas, however, leads in job gains, which is a testament to our state's resilient economy. Yet, we must acknowledge that the 25% increase in the two-year state budget last year was excessive. This surge in spending did not provide sufficient property tax relief, which is critical for maintaining economic vitality and keeping Texas attractive for businesses and residents alike. Moreover, we must prioritize universal school choice next year to ensure educational opportunities that meet diverse needs and drive future economic growth. Election Year Volatility During election years, the stakes are even higher. Uncertainty about future policies can cause volatility in markets and economic performance. For instance, debates over infrastructure funding, environmental regulations, and tax policies can create an unstable business environment. Companies may delay or cancel projects, affecting the demand for aggregates and concrete. This uncertainty trickles down, impacting jobs, investments, and overall economic health. Aggregates and concrete are essential for the development and maintenance of our infrastructure. These materials for things like highways and homes are our physical landscape's backbone. However, it's crucial to approach their use smartly. We don't need to resort to industrial policies with high costs and trade-offs, burdening taxpayers. Instead of a top-down approach, which often fails due to bureaucratic inefficiencies, we should consider a bottom-up approach to transportation projects. This includes government projects, public-private partnerships, and private projects. A significant portion of infrastructure could be managed through private toll roads. While my ideal vision leans heavily on privatization and tax cuts, I recognize that a balanced approach is more realistic in the current environment. Public-private partnerships can bring innovation and efficiency, reducing the burden on taxpayers while still delivering essential infrastructure. Let me share an example from my work. My research finds that private toll roads can often be built faster and cheaper than public projects. Private companies are directly incentivized to minimize costs and maximize efficiency. For instance, the LBJ Express project in Dallas, a public-private partnership, was completed ahead of schedule and under budget, demonstrating the potential benefits of such collaborations. There is also a need to move to design-build for projects in Texas rather than today's more costly and time-consuming design-bid-build approach. Additionally, Texas is experiencing significant population growth, with more people moving to the state, increasing the demand for our infrastructure. The Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) is investing in expanding highways and improving ports to accommodate this growth. Projects like the $7.5 billion North Houston Highway Improvement Project aim to address these demands. However, we must ensure that these investments are managed efficiently and effectively. Role of Institutions and Central Planning Another key aspect is the role of institutions. Friedrich Hayek, in his book "The Road to Serfdom," cautioned against the overreach of central planning. He emphasized that central planning often leads to inefficiencies and a loss of individual freedoms. His insights are particularly relevant today as we navigate the complexities of modern infrastructure development. To truly flourish, Texas needs to embrace more free-market capitalism and resist the creeping influence of socialism in our economy. This applies to transportation and beyond. By focusing on the efficient use of resources, reducing regulatory burdens, and fostering competition, we can build a more prosperous future. The bottom-up approach not only ensures better utilization of resources but also empowers local communities to take charge of their development, aligning projects more closely with the actual needs and priorities of the people. Consider the example of toll roads in other states. Using private toll roads in Virginia has significantly improved traffic flow and reduced congestion in previously bottleneck areas. This model can be replicated in Texas, where traffic congestion is growing, especially in urban areas. By allowing private companies to manage and maintain these roads, we can ensure they are kept in optimal condition without continuously draining public funds. Furthermore, private toll roads can be a source of innovation. Companies can introduce advanced technologies for traffic management and toll collection, making the entire system more efficient. For example, using electronic toll collection systems in Florida has greatly reduced vehicles' time at toll booths, enhancing the overall travel experience. However, this doesn't mean we should eliminate public involvement in infrastructure projects. There are instances where government intervention is necessary, especially in projects that may not be immediately profitable but are crucial for public access and economic activity. This is where public-private partnerships come into play, allowing us to leverage the strengths of both sectors. The government should act as a facilitator rather than a direct manager of projects. By setting clear regulations and standards, it can ensure that private companies operate fairly and efficiently while also protecting the interests of the public. This approach can help us avoid the pitfalls of excessive government control while still reaping the benefits of private sector efficiency. Paul Krugman and other progressives might argue that significant government intervention is necessary to address market failures and ensure equitable outcomes. They believe that without government oversight, critical infrastructure could suffer from underinvestment, and social inequalities could worsen. While these points are worth considering, history has shown us that excessive government control often leads to inefficiencies, higher costs, and reduced innovation. Learning from Failures and Future Outlook My journey from poverty to rockstar to entrepreneurial economist taught me the value of strong institutions and the importance of aligning personal purpose with societal needs. This principle applies to our infrastructure as well. Just as a solid foundation is critical for a stable building, a robust institutional framework is essential for a thriving economy. We must ensure that our policies and investments in infrastructure reflect this understanding. As we look toward the future, we must remain vigilant against the encroachment of socialist policies that threaten to undermine the free-market principles that have made Texas a beacon of prosperity. Instead, we should champion policies that promote individual liberty, economic freedom, and responsible stewardship of resources. Failure provides us with valuable lessons, and too often, people want to mitigate this by expanding government intervention, which can be detrimental to our learning and growth. We are at a critical juncture in our state's history. The recent elections have shown us that Texans are ready for a change. The upcoming November elections present another opportunity to reaffirm our commitment to the principles that have made Texas great. While I am optimistic about our future, we must address the economic, political, and cultural challenges that threaten our way of life. Election Year Volatility and Policy Uncertainty One of the most pressing issues is the rise of big government. Across the political spectrum, there is a growing tendency to rely on government intervention to solve problems. This trend is particularly concerning in Texas, where we have traditionally prided ourselves on independence and self-reliance. Many of you might be demanding the government give you handouts or reap the benefits of federal, state, or local spending, but all this comes from taxpayers' pockets. We must try a different approach. Election year volatility adds another layer of complexity. Businesses and investors are left guessing about the future as policies swing with the political tide. This uncertainty can stall projects, delay investments, and increase costs. The aggregates and concrete industry, heavily reliant on long-term planning and stability, feels these effects acutely. Conclusion In conclusion, aggregates and concrete are vital for Texas's growth, but their smart use is paramount. Let's leverage the strengths of the free market, prioritize efficiency, and ensure that our infrastructure investments truly benefit Texans. As we progress, I am eager to collaborate with any of you on projects aligning with these principles. Together, we can build a stronger, more prosperous Texas. For those interested in further discussions on economic policy and free-market solutions, I invite you to check out my podcast, the Let People Prosper Show on all major platforms, and my Substack newsletter at vanceginn.substack.com, where I delve into these topics in greater detail. You can also visit my website, VanceGinn.com, for more information and resources. Thank you for your time and attention. Let's work together to build a future where smart infrastructure investment and strong institutions pave the way for a prosperous Texas. Property taxes in Wyoming have increased dramatically, placing a substantial burden on taxpayers. This proposal outlines a bold, practical plan to eliminate property taxes through disciplined government spending and targeted surplus distribution to reduce school district property taxes.

Property Taxes are Growing Too Fast:

Process for Eliminating Property Taxes: The proposed process involves three critical steps aimed at systematically reducing and eventually eliminating property taxes while fully funding state government operations and school districts:

Expected Outcomes

Economic Gains

Conclusion This proposal seeks to relieve Wyoming residents of the oppressive property tax burden. The discipline it imposes on state spending directly benefits all Wyoming taxpayers – surplus money flows back into their pockets, not into government accounts to be spent by politicians. Achieving this bold reform will allow Wyoming to flourish now and for future generations. Full research paper here. Originally published at Marketplace.

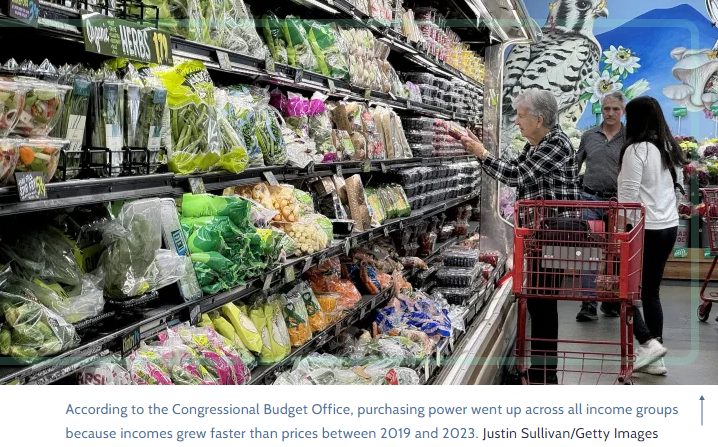

Inflation numbers came in better than expected this week, and they’re the latest in several months of data showing that price growth has slowed down. Another way to look at inflation came out from the Congressional Budget Office this week, looking at the issue from the lens of purchasing power. The CBO found that if you look at the same basket of goods from pre-pandemic to 2023, on average, Americans need less of their income to buy the same set of stuff. But if that just feels a bit off to you, I get it. According to the Congressional Budget Office, purchasing power went up across all income groups because incomes grew faster than prices between 2019 and 2023. “That kind of goes against the common perception of what’s going on is that people are losing purchasing power over the last few years,” said Vance Ginn who is president of Ginn Economic Consulting and was a White House chief economist during the Trump administration. The CBO found, percentage-wise, folks in the highest income bracket spent less of their income on common expenses — down 6.3%, thank you stock market. Folks in the lower income brackets weren’t so lucky. They saw only a two percent drop in how much they spent on basics, thanks to higher wages. But for people in the middle, it was even less noticeable. “And that’s why I think they’ve been, kind of, not being able to be as prosperous as some of the others during this period,” said Ginn. Plus these numbers reflect averages, not people’s individual experiences. And that’s where narratives really come into play, especially in an election year. “We did go through a period of about 18 months of very elevated inflation. But it’s also true that prices today are rising roughly in line with previous historical experience,” said Michael Linden, a Senior Policy Fellow at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth. And in campaign ads and in stump speeches we’ll probably end up hearing versions of both inflation stories, amplified in whichever direction benefits the candidate talking. “And I think that the American people are going to have to decide when they hear about inflation, which of those two things is more important to them,” said Linden. And whose narrative about the economy you choose to believe. Originally published at Kansas Policy Institute.

The death of HB 2663 in Kansas, which aimed to create new Sales Tax and Revenue (STAR) Bonds and Tax Increment Financing (TIF) districts for financing new sports stadiums, has reignited critical debate about the role of public funding in private projects. The bill also provided 100% financing for 30 years to attract the Kansas City Chiefs or Royals to new stadiums on the Kansas side of the KC Metro area. This follows after 58% of Jackson County voters wisely rejected a $2 billion subsidy for similar developments, highlighting a disconnection between rent seekers and the electorate’s preferences. These initiatives exemplify a deeper issue with economic development strategies that lean heavily on corporate welfare, undermining the principles of free-market capitalism that has long-supporting abundant prosperity. While Kansas ranks just 26th in its state business tax climate according to the Tax Foundation and 27th in economic outlook according to the American Legislative Exchange Council, picking winners and losers is the wrong approach. Stadium subsidies are intended to attract teams, showcasing the immediate allure of new facilities and jobs—the ‘seen’ effects. Yet, the ‘unseen’ consequences, including diverting substantial public funds from better uses and imposing long-term fiscal burdens on taxpayers, are far more concerning. Instead of acting as a neutral facilitator of economic activity, governments too often play favorites through these tax incentives, leading to market distortions and cronyism. The implications are significant: businesses spend more time lobbying for these financial boosts than focusing on consumer-driven growth and innovation. Milton Friedman famously criticized such government spending, stating, “There is nothing so permanent as a temporary government program.” In this context, the subsidies intended to be a short-term boost can lead to prolonged financial strain on public resources. Historically, STAR Bonds have fallen short of their promise to boost the commercial, entertainment, and tourism sectors. Despite using them for over two decades, these bonds have not elevated consumption in Kansas’s tourist-related sectors above the national average. Over a decade, tourist-related spending has notably declined, falling 20 percentage points below what might be expected compared to other states. This stark underperformance underscores the inefficacy of STAR Bonds in stimulating genuine economic growth. Moreover, the promise of job creation through such subsidies is often misleading. An analysis by the Kansas Policy Institute of Wichita’s Riverwalk and K-96/Greenwich STAR Bonds demonstrated that these projects did not spawn new employment but merely shifted jobs within the eastern side of Wichita, let alone the state. This job redistribution, rather than creation, suggests that such fiscal tools are not just ineffectual but harmful, as they concentrate development in ways that don’t align with the broader community interests. As manifested in STAR Bonds, corporate welfare fundamentally distorts the free market. It prompts businesses to seek profitability through government aid rather than market-driven innovation and efficiency. This misallocates precious resources and dampens the entrepreneurial spirit, crucial for real economic progress. Of course, many Kansans support the Royals or the Chiefs. These sports teams are part of the community and should be celebrated. And yet, they’re private businesses, and subsidizing their operations from the paychecks of someone in Edwardsville or Ellis County hardly seems appropriate. No matter how much you may cheer for Salvador Perez hitting a homer or Patrick Mahomes throwing another touchdown, these subsidies are no different than spending your paycheck to entire a battery factory in The Sunflower State. Milton Friedman argued that the government’s role should not be to determine economic winners and losers but to facilitate a stable environment that supports voluntary exchanges and organic growth. Therefore, policies should aim to reduce government expenditure, lower tax burdens, and ease regulations that impede business operations, fostering a climate where businesses can thrive on their merit. Moreover, funding these projects involves increased taxes or reallocating municipal funds, burdening local economies. The long-term financial commitments can lead to higher taxes elsewhere or cuts in essential services. Studies, such as those by the Brookings Institution, consistently show that stadium subsidies do not significantly increase local tax revenues or long-term employment growth. Instead, they often serve as handouts to billionaires at the expense of ordinary taxpayers. Despite its setbacks, the rejection of HB 2663 should be viewed as a protective measure against the continuation of flawed economic policies. It affirms commitment to market efficiencies over flashy, unproductive government expenditures. Policymakers must focus on long-term, sustainable strategies that benefit the wider population. With a special session looming, the idea of legislative-enacted, taxpayer-subsidized stadiums could still be alive in 2024. It’s troubling that while HB 2663 never got traction, the legislature actively removed oversight from some state incentive programs. Kansas must continue challenging economically unsound proposals and advocate for policies that lower business costs through reduced government spending, lower taxes, and less regulation. By promoting a more free-market environment, the state will ensure long-term economic health and prosperity for all Kansans, not just a select few. Originally published at The Center Square.

Iowa Gov. Kim Reynolds and the Republican-led Legislature have emphasized conservative budgeting as a central priority. Such prudence in budgeting is the cornerstone of fiscal conservatism, and the recent passage of the FY 2025 budget in Iowa highlights a commitment to fiscal restraint, albeit less stringent than in previous sessions. The newly approved $8.9 billion FY 2025 General Fund budget marks a 4.7 percent increase from the previous fiscal year's $8.5 billion, demonstrating moderate fiscal growth. Historically, spending has been recommended to align with the combined rates of population growth and inflation. Based on this formula, the FY 2024 budget of $8.5 billion should ideally have capped the FY 2025 spending at $8.8 billion. Adhering to such metrics ensures that the budget reflects the average taxpayer's ability to fund it, a fundamental principle that should guide all budgetary decisions. This year, however, the legislature has ventured slightly beyond this benchmark, underscoring the careful balance between fiscal responsibility and the needs of a growing state. To provide substantial relief to individual taxpayers, the legislature has implemented a significant income tax cut, which accelerates the implementation of a 3.8 percent flat tax in 2025. This measure is projected to save taxpayers over $1 billion. The tax relief directly benefits Iowans, putting more money back into their pockets and supporting more economic growth. Despite concerns from critics who argue that such fiscal strategies could undermine public services, the FY 2025 budget demonstrates that the government is not retrenching but rather growing at a deliberate pace. Education remains a top priority, accounting for 56 percent of the budget. When combined with the allocations to the Department of Human Health Services (DHHS), these two areas consume a significant 81 percent of the General Fund. While this concentration of funds reflects the importance placed on these sectors, it also highlights the challenges of allocating resources to other critical areas, such as public safety and the judicial system, which have only seen modest increases. The practice of conservative budgeting is further evidenced by the state's adherence to its legal spending cap, which allows up to 99 percent of projected revenue to be used. In contrast, the FY 2025 budget only commits 92 percent of these projections, reinforcing Iowa's fiscal discipline. This cautious approach is proving effective, as evidenced by the substantial budget surpluses recorded in recent years, including a $1.8 billion surplus in FY 2023, with similar surpluses anticipated for FY 2024 and FY 2025. Looking ahead, legislators must remain vigilant to ensure that conservative budgeting principles continue to guide fiscal policy. State Sen. Jason Schultz rightly points out the interdependence of tax policy and spending, “Both Republicans and Democrats need to realize that tax policy is affected by spending. And when you start seeing spending creeping up for annual, year after year, new good ideas, you can’t have good tax policy.” Strengthening Iowa's 99 percent spending limitation would provide a robust mechanism to curb future expenditure desires. This could be done by changing the law and enshrining it in the Constitution to bind spending increases to no more than the rate of population growth plus inflation. Iowa’s fiscal approach starkly contrasts the situations unfolding in neighboring states like Minnesota and Illinois or others such as New York and California. Higher spending and taxes in these progressive states contribute to economic challenges and drive more people away. The message is clear: unsustainable increases in spending can lead to severe consequences. Iowa's success in maintaining fiscal discipline through conservative budgeting and responsible tax policies is a testament to the effectiveness of this approach. Iowa’s unwavering commitment to conservative budgeting and responsible tax policies is the cornerstone of its fiscal strategy, ensuring the state remains a model of stability and prosperity. By striking a balance between providing essential services and fostering economic growth, Iowa sets a commendable example of how sustainable fiscal policies can safeguard a state’s financial health and support the well-being of its citizens. Dive into this week's hot economic topics in just 12 minutes on "This Week's Economy"! 🕒

I tackle big questions: 🌍 Are humans driving climate change? 📊 What's the latest in the U.S. labor market? 🌟 How are Texas and Louisiana setting examples of prosperity? Don’t just listen—engage! Share your thoughts, rate me, and leave a review. For in-depth insights and show notes, subscribe to my Substack at vanceginn.substack.com or visit vanceginn.com. #economy #SocialSecurity #Medicare #ClimateChange Originally published at The Courier.

By John Hendrickson and Vance Ginn, Ph.D. Iowa Governor Kim Reynolds and the Republican-led Legislature have emphasized conservative budgeting as a central priority. Such prudence in budgeting is the cornerstone of fiscal conservatism, and the recent passage of the FY 2025 budget in Iowa showcases a commitment to fiscal restraint, albeit less stringent than in previous sessions. The newly approved $8.9 billion FY 2025 General Fund budget marks a 4.7 percent increase from the previous fiscal year's $8.5 billion, demonstrating moderate fiscal growth. Historically, spending has been recommended to align with the combined rates of population growth and inflation. Based on this formula, the FY 2024 budget of $8.5 billion should ideally have capped the FY 2025 spending at $8.8 billion. Adhering to such metrics ensures that the budget reflects the average taxpayer's ability to fund it, a fundamental principle that should guide all budgetary decisions. This year, however, the legislature has ventured slightly beyond this benchmark, underscoring the careful balance between fiscal responsibility and the needs of a growing state. To provide substantial relief to individual taxpayers, the legislature has implemented a significant income tax cut, reducing the flat tax rate to 3.8 percent. This measure is projected to save each taxpayer over $1 billion annually. The tax relief directly benefits Iowans, putting more money back into their pockets and supporting more economic growth. Despite concerns from critics who argue that such fiscal strategies could undermine public services, the FY 2025 budget demonstrates that the government is not retrenching but rather growing at a deliberate pace. Education remains a top priority, accounting for 56 percent of the budget. When combined with the allocations to the Department of Human Health Services (DHHS), these two areas consume a significant 81 percent of the General Fund. While this concentration of funds reflects the importance placed on these sectors, it also highlights the challenges of allocating resources to other critical areas, such as public safety and the judicial system, which have only seen modest increases. The practice of conservative budgeting is further evidenced by the state's adherence to its legal spending cap, which allows up to 99 percent of projected revenue to be used. In contrast, the FY 2025 budget only commits 92 percent of these projections, reinforcing Iowa's fiscal discipline. This cautious approach is proving effective, as evidenced by the substantial budget surpluses recorded in recent years, including a $1.8 billion surplus in FY 2023, with similar surpluses anticipated for FY 2024 and FY 2025. Looking ahead, legislators must remain vigilant to ensure that conservative budgeting principles continue to guide fiscal policy. State Senator Jason Schultz rightly points out the interdependence of tax policy and spending, “Both Republicans and Democrats need to realize that tax policy is affected by spending. And when you start seeing spending creeping up for annual, year after year, new good ideas, you can’t have good tax policy.” Strengthening Iowa's 99 percent spending limitation would provide a robust mechanism to curb future expenditure desires. This could be done by changing the law and enshrining it in the Constitution to bind spending increases to no more than the rate of population growth plus inflation. Iowa’s fiscal approach starkly contrasts the situations unfolding in neighboring states like Minnesota and Illinois or others such as New York and California. Higher spending and taxes in these progressive states contribute to economic challenges and drive more people away. The message is clear: unsustainable increases in spending can lead to severe consequences. Iowa's success in maintaining fiscal discipline through conservative budgeting and responsible tax policies is a testament to the effectiveness of this approach. Iowa’s unwavering commitment to conservative budgeting and responsible tax policies is the cornerstone of its fiscal strategy, ensuring the state remains a model of stability and prosperity. By striking a balance between providing essential services and fostering economic growth, Iowa sets a commendable example of how sustainable fiscal policies can safeguard a state’s financial health and support the well-being of its citizens. John Hendrickson serves as policy director of Iowans for Tax Relief Foundation, and Vance Ginn, Ph.D., is a contributing scholar at ITR Foundation and former chief economist at the Office of Management and Budget, 2019-20. Originally published at Texans for Fiscal Responsibility. Executive Summary

Could Colorado become one of the seven states with no income tax? Vance Ginn, former White House Office of Management and Budget, believes the state is on the #Path2Zero.

Originally published at Washington Times.

In President Biden‘s recent State of the Union address, he painted a rosy economic picture, touting what he called “Bidenomics” as the driving force behind what he claims is a robust economy. He pointed to a low unemployment rate, the absence of a recession, and a lower inflation rate as evidence of success. Reality, however, tells a different story. And Mr. Biden’s recently released irresponsible budget sends the federal government and America further toward bankruptcy. Despite the president’s assertions, the economy and inflation remain top concerns for most Americans. The disconnect between the headlines and the lives of ordinary citizens underscores the profound challenges facing the nation’s economic landscape. This sense of malaise can be directly attributed to the flawed principles underlying Bidenomics, as outlined in his latest budget. These include excessive spending, taxation and regulation. Each is destructive, but together, they are catastrophic. The result has been stagflation and less household employment in four of the last five months. There have also been lower inflation-adjusted average weekly earnings by 4.2% since January 2021, when Mr. Biden took office. Rather than fostering economic growth and prosperity, Bidenomics has stifled innovation, investment and job creation. At its core, Bidenomics represents a misguided attempt to address complex economic issues through heavy-handed government intervention. While the administration may tout short-term gains, the long-term consequences of such policies are far-reaching and unaffordable. The reality is that excessive government spending has led to unsustainable levels of debt, burdening future generations with the consequences of fiscal irresponsibility. Similarly, excessive taxation is stifling entrepreneurship and dampening economic activity, limiting opportunities for individuals and businesses alike. Excessive regulation serves only to hamper innovation and drive up costs, exacerbating the challenges facing working families. Unfortunately, Mr. Biden’s latest budget proposal doubles down on these bad policies. Even with rosy assumptions of tax collections being a higher share of economic output over time as the tax hikes will reduce growth and, therefore, lower taxes as a share of gross domestic product, the budget continues massive deficits every year. This will result in higher interest rates, higher inflation, more investment These results have been highlighted in economic theory by economists such as Alberto Alesina and John B. Taylor. Their research has found that raising taxes doesn’t help close budget deficits because of the reduction in growth from higher taxes in a dynamic economy. The way forward should be cutting or at least better-limiting government spending — the ultimate burden of government on taxpayers. Amid these challenges, America also needs a return to optimism and flourishing. This includes leadership that inspires confidence, fosters innovation, and empowers people to pursue their dreams. We need out-of-the-box policies prioritizing economic freedom and individual opportunity, allowing the entrepreneurial spirit to thrive and driving growth and prosperity. More specifically, this means reducing the burden of government intervention through lower spending and taxes, streamlining regulations, and fostering an environment where entrepreneurship can thrive. By embracing fiscal sustainability and making tough choices, we can ensure the long-term stability and prosperity of our nation. In short, while Mr. Biden tries to spin a positive narrative about the economy, the facts speak for themselves. We cannot afford Bidenomics, no matter the headlines, what was touted in the State of the Union address, or the latest budget. The stakes are too high, and the consequences too grave, to ignore the reality of our economic situation. We need leadership that is willing to confront the hard truths and enact policies that prioritize the well-being of all Americans, fostering an environment where optimism and flourishing can thrive. Originally published at Law & Liberty.

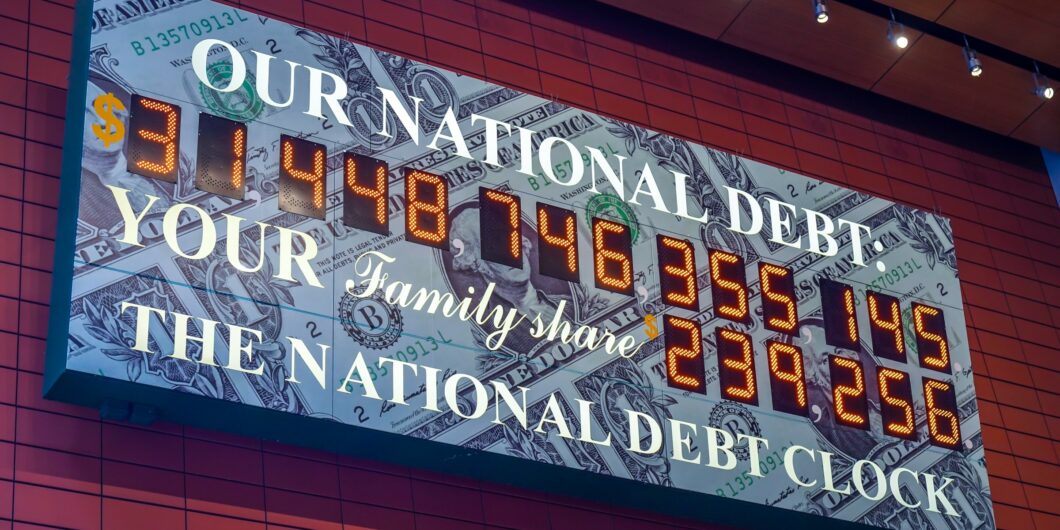

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) just released the February 2024 Budget and Economic Outlook, and projections look grim. This year, net interest cost—the federal government’s interest payments on debt held by the public minus interest income—stands at a staggering $659 billion in 2023 and has recently soared to about $1 trillion. Unless politicians face these facts and restrain spending, Americans can expect rising inflation and painful tax hikes without improvement in public services. Some politicians quickly blamed a lack of tax revenue, calling for repealing the 2017 Trump tax cuts. But how much more money can they take? New IRS data shows that 98% of all income taxes are paid by the top 50% of income earners, those making at least $46,637. Moreover, 35% of Americans feel worse off than 12 months ago and inflation remains the primary concern for those across the income spectrum. So perhaps, rather than taking more money, the government should own up to its mistakes. The massive net interest costs result from bad spending habits, not a lack of revenue. This requires the federal government to adopt strict fiscal and monetary rules to rein in wasteful deficit spending and money printing that fuel higher interest rates and inflation. Net interest cost is the second largest taxpayer expenditure after Social Security and is higher than spending on Medicaid, federal programs for children, income security programs, or veterans’ programs. And it’s expected to grow. The CBO projects net interest to surpass Medicare spending this year and balloon to $1.6 trillion in 2034 as a result of higher debt and higher interest rates. Interest rates on Treasury debt are at the highest since 2007, paying between 4% and 5.5%, and the rates are expected to rise further. As the stockpile of gross federal debt is expected to grow by about $20 trillion to $54 trillion over the next decade, politicians will face an increasing temptation to rely on the Federal Reserve to pay for it by printing money. If the Fed does, the dollar’s value will decline, and Americans will continue to struggle financially. In an ideal world, politicians will organize the budget process to focus on funding a limited government and ensuring Americans keep their hard-earned money. They would also have plans to cut spending during times of economic downturn to reduce tax burdens on families and businesses and avoid the Keynesian fallacies of deficit spending to fill gaps in economic growth. However, America isn’t Shangri-La. As Thomas Sowell poignantly notes, a politician’s first goal is to get elected, the second goal is to get reelected, and the third goal is far behind the first two. So long as there are investors happy to purchase Treasury debt, there will be politicians who are happy to sway voters with generous spending programs financed by public debt. This must end. Instead, Washington should require strong institutional constraints with a spending limit. The limit should cover the entire budget and hold any budget growth to a maximum rate of population growth plus inflation. This growth limit represents the average taxpayer’s ability to pay for spending. Following this limit from 2004 to 2023 would have resulted in a $700 billion debt increase instead of the actual increase of $20 trillion. Such a policy has been in effect in Colorado since 1992. It is the Taxpayer’s Bill of Rights (TABOR) amendment to the Colorado Constitution. TABOR has revenue and expenditure limitations that apply to state and local governments. The revenue limitation applies to all tax revenue, prevents new taxes and fees, and must be overridden by popular vote. Expenditures are limited to revenue from the previous year plus the rate of population growth plus inflation. Any revenue above this limitation must be refunded with interest to Colorado citizens. A spending cap like TABOR is necessary but not sufficient to solve the problem because politicians in Washington can still pressure the Federal Reserve to pay for the increased debt by printing money. Therefore, it must be combined with a monetary rule to force fiscal sustainability while requiring sound money with fewer distortions in the economy. Monetary rules can come in many forms. While no rule is perfect, research shows that a rule-based monetary policy can result in greater stability and predictability in money growth than the current policy of “Constrained Discretion” whereby the Fed follows rules during “normal times” and has discretion during “extraordinary times.” Whether we are in ordinary or extraordinary times is up to policymakers, who typically don’t want to “let a good crisis go to waste,” as they say. Milton Friedman advocated for a money growth rate rule, the “k-percent rule.” This rule states that the central bank should print money at a constant rate (k-percent) every year. A variation of this rule was used by Fed Chair Paul Volcker in the late 1970s and early 1980s to tackle the Great Inflation with much success. Unfortunately, the Fed had already done too much damage with excessive money growth before then, so the cuts to the Fed’s balance sheet contributed to soaring interest rates that forced destructive corrections in the economy, resulting in a double-dip recession in the early 1980s. This led to the Fed abandoning money growth targeting in October 1982. It is important to note, though, that this “monetarist experiment” was not bound to any law, constitutional or statutory. During that time, the Fed still operated under discretion, which is why it was able to abandon the monetary growth rule just a few years after it had begun, unfortunately. There are other rules that could be applied. John Taylor proposed what’s been coined the Taylor Rule, which estimates what the federal funds rate target, which is the lending rate between banks, should be based on the natural rate of interest, economic output from its potential, and inflation from target inflation. Scott Sumner most recently popularized nominal GDP targeting, which uses the equation of exchange to allow the money supply times the velocity of money to equal nominal GDP. It has different variations, but the key is that velocity changes over time, so the money supply should change based on money demand to achieve a nominal GDP level or growth rate over time. By focusing on a rules-based approach to spending and monetary policy, Americans do not have to worry about electing the perfect candidate every election. Proper constraints will nudge even the worst politicians to make fiscally responsible choices and reduce net interest costs. Furthermore, America will be better positioned to respond to crises at home and abroad. If Congress wants to see who is to blame for the grim CBO projections, they should look in the mirror. Stop looking to take hard-earned money away from Americans and focus on sound budget and monetary reforms now. Originally published at The City Journal.

In November 2023, Texas voters approved a constitutional amendment, HJR 2, which Governor Greg Abbott said would “ensure more than $18 billion in property tax cuts—the largest property tax cut in Texas history.” Texas homeowners’ hopes were dashed at the start of 2024, however, when they got their property tax bills. The promised $18 billion reduction amounted to only $12.7 billion in new property tax relief, a fraction of the state’s record $32.7 billion budget surplus, while the other $5.3 billion merely maintained property tax relief from years past. While Texas doesn’t have a state income tax, it does have the nation’s sixth-most burdensome property taxes. These taxes obstruct peoples’ ability to buy homes and price others out of the homes they’re in. Texans expect and deserve clarity about their property tax bills, but state policymakers’ failed promises and lack of transparency have eroded public trust. Despite the governor’s claim, the 2023 tax relief package, spread over two years, isn’t even the state’s largest historic property tax cut. In 2006, the Texas legislature apportioned $14.2 billion to reducing residents’ property taxes, cutting school district maintenance and operations (M&O) property tax rates by a third for 2008–09 biennium, and making up the difference with a revised franchise tax, a higher cigarette tax, and a higher motor vehicle sales tax. Adjusted for inflation, 2023’s cut would have had to exceed $21 billion to surpass the 2006 cut. The new package's biggest achievement was saving taxpayers $5 billion in 2023 by reducing the maximum school district M&O property tax rate by 10.7 cents per $100 valuation; it also raised the homestead exemption of taxable value for school district M&O property taxes to $100,000 and limited appraisal-value increases to 20 percent for other property. And yet, Texans’ total property taxes paid in 2023 nevertheless rose by $165.2 million over 2022, an overall increase of 0.4 percent. That net increase came from school district tax hikes to fund more debt ($890.2 million); municipal governments ($1.3 billion); county governments ($1.5 billion); and special purpose districts ($1.5 billion). These hikes effectively washed away state-level reductions. While this result is ultimately the fault of local governments, the state should have done more to provide relief and restrict localities’ spending and taxes. This growth in local property tax collections is part of a larger trend. From 1998 to 2023, Texas’s total property taxes collected rose 338 percent while the rate of population growth plus inflation was just 136 percent. No wonder so many Texans feel as though they are being crushed by housing unaffordability. How can Texas fix its spending problem? Rather than resort to temporary fixes, the state needs a robust spending cap in its constitution like Colorado’s Taxpayer’s Bill of Rights (TABOR), which limits state and local government spending increases to no more than the rate of population growth plus inflation. Though Colorado’s TABOR has been the gold standard for a state spending limit since its enactment in 1992, it can be improved. At this time, TABOR applies to Colorado’s general revenue, less than half of its total funds; it should be expanded to apply to all state funds, which would account for about two-thirds of its budget, as originally intended. Texas, or Colorado itself, could also improve the model by replacing the latter’s policy of refunding excess tax revenue to taxpayers with up-front income-tax-rate cuts. Texas enacted a statutory spending limit in 2021, but it lacks teeth, as an overriding constitutional spending limit covers just 45 percent of the budget and can be exceeded by a simple majority. In conjunction with a stronger constitutional spending limit, the Texas legislature should implement strategic budget cuts. These efforts combined with the stricter constitutional spending limit would create opportunities for surpluses at the state and local levels, which would pave the way for the state to reduce school M&O property taxes annually until they are fully eliminated. This alone would shave off nearly half of the property tax burden in Texas. Viewed from the coasts, Texas is a beacon of economic freedom. But as its spending and property tax data show, it isn’t perfect. The Texas legislature should acknowledge its failed promises and deliver real property tax relief for its citizens. Originally published at Dallas Express.