|

This commentary originally appeared in Investor's Business Daily on May 26, 2017.

After suffering from rising federal tax and regulatory burdens, Americans may be on the precipice of the next huge economic expansion. The evidence is already mounting as business and consumer confidence reach new highs after the Trump administration's regulatory reforms and other pro-growth proposals. The next impetus to support increased prosperity is cutting government spending and taxes. President Trump's announced tax plan would cut the federal corporate income tax rate of 35%, the highest in the industrialized world, to a more competitive 15%. The plan would also reduce the number of personal income tax brackets from seven to three, double the standard deduction, and eliminate the death tax, Alternative Minimum Tax, and all deductions except for mortgage interest and charitable contributions. The president's plan is similar to the GOP tax plan but unique in a number of ways. A major difference is the GOP's inclusion of what's been called a "border adjustment tax," or BAT, which is simply a new way of taxing business cash flow. Specifically, the BAT would keep the corporate income tax base on goods produced and sold domestically but change the base from exports to imports. One reason for pushing the BAT is to achieve revenue neutrality, which is when tax cuts are offset with increases in other taxes, but the GOP proposal could add to the current $20 trillion in national debt over the next decade. Moreover, by favoring domestic goods over imported goods, the BAT will distort international trade and its associated benefits, which would harm economic activity. Some economists favor the BAT, claiming it will level the playing field between imports and exports. Moreover, they speculate that the dollar's value will adjust to the BAT so that it doesn't cause increases in consumer and producer prices or change production patterns. While these arguments theoretically could happen, they exclude how the BAT would result in less economic growth through at least the following three ways:

As an example of the cost of the BAT, the Texas Public Policy Foundation and the R Street Institute commissioned a study that found the BAT could contribute to a cost increase of $3.4 billion in Texas' property-casualty insurance premiums over the next decade from its effect on the reinsurance market. To avoid these large costs, Congress should focus on cutting taxes while slaying what drives increases in national debt: government spending. For every dollar of taxes cut, Congress should cut a dollar in government spending. This pro-growth combination would assure no additional increase in projected deficits under current policy. In addition, this approach would support increased economic growth that would contribute to more taxes collected, resulting in reduced projected deficits. The starve-the-beast approach, with the goal of reducing the size and scope of government, has been tried before from historic tax cuts under the administrations of Kennedy-Johnson, Reagan and Bush 43. However, in each case, government spending rose faster than increased tax collections, resulting in substantially more national debt. To reduce the federal tax and regulatory burdens that hinder economic growth this time around, Congress should pursue a "budget neutral" approach of cutting both taxes and government spending. Fortunately, President Trump's announced tax plan doesn't focus on revenue neutrality by including the BAT. This provides an opportunity for a discussion about taming excessive government spending. Federal tax reform should focus on core principles of taxation that include a simple, efficient and competitive tax system. President Trump's tax proposal heads in that direction. By following these principles and focusing on cutting government spending to achieve budget neutrality, without creating a costly BAT, Americans can be more prosperous and optimistic about their future.

0 Comments

Here are my thoughts on the border adjustment and federal tax reform in general as they could influence the U.S. economy, especially Texas.

I disagree with some of the analysis and findings by Kotlikoff (see full article below), whom is a highly respected economist regarding life cycle economic modeling and analysis, but he tends to be Keynesian in his approach, as you can see throughout his piece. Much of what he states about the border adjustment, also known as the border adjustment tax (BAT) though it is not technically a tax, is reflected in the Tax Foundation’s (TF) talking points. TF claims that the border adjustment will be more efficient than our current corporate income tax system by leveling the playing field for goods that are consumed in the U.S. Moreover, TF argues that it is not a tax but rather a “border adjustment” of the current corporate income tax such that corporations report consumption of their imported goods as income since it is consumed here instead of exports that are consumed elsewhere. TF and Kotlikoff also put a lot of emphasis on the far-reaching assumption that the dollar value will adjust accordingly to not make the border adjustment cause increases in consumer and producer prices. While theoretically TF is correct on several points, the BAT argument fails on at least the following levels:

Tax revenue neutrality is a failed argument that has been tried multiple times (e.g., Kennedy-Johnson tax cuts, Reagan tax cuts, Bush tax cuts); tax reform should focus on budget neutrality such that the economic drain of a rising $20 trillion in federal debt is plugged as soon as possible. The vision, like in Texas, should be to not tax businesses that simply submit taxes to the government while people pay the actual cost through the form of higher prices, lower wages, and fewer jobs available. In economic terms, the tax incidence is ultimately on people. Ending the corporate income tax would eliminate whether we are taxing income based on imports or exports, removing the concern over the border adjustment. Considering we are unlikely to eliminate federal taxes on businesses today, reducing the corporate tax rate to as low as possible while not changing the tax base, thereby distorting the marketplace more than it should, balancing the budget should be based on economic growth and slowing and cutting government spending so budget neutrality is achieved. There’s no need to add a “new tax,” though it’s not technically a new tax, in the form of the border adjustment. The Texas Public Policy Foundation (TPPF) recently commissioned a study with the R Street Institute that highlights the cost increase of $3.4 billion in Texas' property-casualty insurance premiums over the next decade from the border adjustment, which is just a small portion of the potential costs to Texas and other states. TPPF's research also shows that taxes on income and higher taxes in general are detrimental to economic activity among states; therefore, shrinking the size and scope of government by cutting government spending is the best path toward prosperity, not providing revenue neutrality with a new border adjustment. Fortunately, President Trump’s announced tax plan does not include the BAT. While I have concerns about the contribution of Trump’s tax plan to the already estimated increases in the national debt from current policy, economic growth will reduce some of the static analysis revenue losses. Considering that neither President Trump's nor the GOP tax plan will pay for itself, as some economists suggest, the focus must be on budget neutrality as Congress cuts and restrains government spending. At this point, I prefer the Trump tax plan and think it would best reduce tax burdens to allow more incentives by entrepreneurs to produce—the driver of economic activity. However, this is an opportunity to highlight that there shouldn’t be taxes on businesses, like TPPF argues to eliminate Texas' business franchise tax, and that the federal government should continue to simplify the tax code to provide more efficiency in the code by moving to a flat tax, which I prefer a flat consumption tax, and subsequent increased economic activity. This is also an opportunity for the U.S. to increase its economic competitiveness through tax reform to counter the unfortunate protectionist arguments in D.C. that could lead to potentially worse negotiated trade deals and fewer beneficial trade agreements, which is very disconcerting. Below are two recent WSJ articles that provides different views on this issue. I hope the debate will continue so that the appropriate institutional framework for fiscal policy will prevail. In general, this framework should be based on the core principles of taxation, which includes simplicity, efficiency, and competitiveness. By following these principles and focusing on budget neutrality without shifting to a new tax base, the U.S. can be more prosperous and Texans will benefit in the process. __________________________________ On Tax Reform, Ryan Knows Better The House proposal beats Trump’s plan, which is more regressive and would induce huge tax avoidance. By Laurence Kotlikoff May 11, 2017 6:58 p.m. ET 172 COMMENTS As Republicans push toward a major rewrite of the U.S. tax code, they must evaluate two competing proposals: the House GOP’s “Better Way” plan and President Trump’s framework, introduced last month. Either would greatly simplify personal and business taxation, but pro-growth reformers should hope that the final package looks more like the House’s proposal. Let’s begin the analysis with personal taxes. Both plans eliminate the alternative minimum tax, deductions for state and local taxes, and the estate tax. The House plan eliminates exemptions, while Mr. Trump’s outline is unclear. Both raise the standard deduction, reduce the number of income-tax brackets, lower the top marginal tax rate, and provide a big break to those with pass-through business income. On this last point the Trump plan is particularly generous. It taxes pass-through income at 15%—far below its proposed top rate of 35% for regular income. The large gap between these rates would induce massive tax avoidance by the rich. The Better Way’s proposed rates are much closer: 25% and 33%, respectively. Another criterion to judge tax reform is its effect on the budget. Absent any economic response, the Better Way proposal would lower federal tax revenue by $212 billion a year, according to a recent study I conducted with Alan Auerbach, an economist at Berkeley. But some economic response is likely. The House plan would cut the U.S. corporate tax rate from one of the highest among developed countries to one of the lowest. Computer simulations—which will be included in a forthcoming journal article I am writing with Seth Benzell and Guillermo Lagarda —suggest that increased dynamism could raise U.S. wages and output by up to 8%. Under this optimistic scenario, federal tax revenue would rise by $38 billion a year. We are in the process of simulating the Trump plan, and it is too early to say whether it produces less revenue. The plan’s potential for tax avoidance, however, is a major red flag. Which plan is more regressive? Both personal tax reforms appear to help the rich. But the Better Way’s business tax reform actually appears highly progressive. Despite the popular perception that the corporate income tax is paid by the rich, my research suggests it represents a hidden levy on workers. This causes American companies and capital to flee the country, reducing demand for U.S. workers, whose wages consequently shrink. The Better Way plan transforms the corporate income tax into something different: a business cash-flow tax with a border adjustment. Notwithstanding innumerable mischaracterizations by the press, politicians and business leaders, the cash-flow tax implements a standard value-added tax, plus a subsidy to wages. Every developed country has a VAT, which is an indirect way to tax consumption. All of these levies have border adjustments, which ensure that domestic consumption by domestic residents is taxed whether the goods in question are produced at home or imported. Unlike the Better Way, Mr. Trump’s plan does not include a border adjustment, which means it effectively taxes exports and subsidizes imports. This undermines his goal of reducing the U.S. trade deficit. Where is the progressive element to the cash-flow tax? It’s in the subsidy to wages, which insulates workers from the brunt of the VAT. They will pay VAT consumption taxes when they spend their paychecks, but they also will have higher wages thanks to the subsidy. The folks who truly pay the cash-flow tax are the rich, because they pay the VAT when they spend wealth that was earned years or decades ago. As my study with Mr. Auerbach shows, this quiet but large wealth tax makes the overall House plan almost as “fair” as the current system. Our analysis—in contrast with studies done by congressional agencies and D.C. think tanks—assesses progressivity based on what people of given ages and economic means get to spend over the rest of their lives. Consider the present value of remaining lifetime spending for 40-year-olds. The richest quintile of this cohort accounts for 51% of the group’s spending, and the poorest quintile for 6.3%. Under the House tax plan, those figures move only modestly, to 51.6% and 6.2%. And the Trump plan? Hard to say, given how easily the rich could transform otherwise high-tax wage income into low-taxed pass-through business income. The Trump tax plan strikes out on all counts. Whoever knew tax reform could be this complicated? We specialists in public finance did. The bottom line is that the U.S. needs more revenue and less spending to close the long-term fiscal gap. The nation’s true debt—the present value of all projected spending, including the cost of servicing the $20 trillion in official debt, minus the present value of all current taxes—has been estimated by Alan Auerbach and Brookings’s William Gale to be as high as $206 trillion. The Better Way plan moves in the right direction, but if the economy doesn’t respond as hoped, there’s a risk of larger deficits. One way to prevent that would be to eliminate the ceiling on earnings subject to the Social Security payroll tax. That could add $300 billion to the Treasury each year, according to our calculations. But even without that adjustment, the House plan seems far superior to both the current system and the Trump plan. The press, politicians, and business leaders should get things straight, including this key point: The Better Way tax plan is indeed a better way. Mr. Kotlikoff, an economist at Boston University, is director of the Fiscal Analysis Center. ______________________________ Economists Say President Donald Trump’s Agenda Would Boost Growth — a Little The WSJ’s monthly survey of economists gauges the impact of a fully implemented Trump plan By Josh Zumbrun Updated May 11, 2017 10:34 a.m. ET 17 COMMENTS One of the most-watched economic forecasts in Washington will come later this month when the White House releases its budget. Here is what it would look like if done by economists surveyed by The Wall Street Journal. Over the course of the next decade, the estimated cost of many items on President Donald Trump’s wish list will depend critically on his own team’s projections for economic growth, unemployment and interest rates. Per the longstanding custom, however, the White House budget differs from most economic forecasts in one crucial way. Most forecasters estimate the path for the economy they believe is most likely, taking into account that many political promises will never come to fruition. But White House forecasts are an estimate of what the economy would be like if the president’s full agenda were implemented. To establish a baseline of what a reasonable forecast might look like under Mr. Trump, respondents to The Wall Street Journal’s monthly survey of forecasters provided their own estimates of the economy if all of Mr. Trump’s initiatives were enacted. If the president’s agenda were enacted, forecasters on average think long-run gross domestic product growth could rise to 2.3%, an 0.3 percentage point increase from their 2% baseline. Unemployment would average 4.4% under this scenario, instead of 4.5%. Interest rates set by the Federal Reserve would be about a quarter-point higher. Short-term rates would be about 3.1%. So an improvement, but a modest one. Early on, White House officials have reportedly considered penciling in growth rates as high as 3.2% a year. But the respondents to the Journal’s survey—a mix of academic, financial and business economists who regularly produce professional forecasts—say numbers so high will be hard to attain, because the policies under consideration just might not pack that punch. Key Trump initiatives, which face a challenging road through Congress, include overhauling the health-care system, simplifying the corporate tax code, cutting income taxes, rewriting regulation and investing in the nation’s infrastructure. “If you were to assume that such initiatives get passed later this year, there should be positive economic benefits, especially for 2018,” said Chad Moutray, chief economist of the National Association of Manufacturers. Over the course of a decade, 3.2% growth would leave the economy nearly $2 trillion larger than 2.3% growth. So the lower estimates of economists are significant. “Fewer regulations may raise long-term growth 0.1% to 0.2% by stimulating productivity growth,” said Nariman Behravesh of IHS Markit Economics. “It should have hardly any effect on the long-term unemployment rate and inflation rates.” It is “hard to quantify, but measures would not boost long-term productivity,” said Ian Shepherdson of Pantheon Macroeconomics. “But they probably would push up both short and long-term interest rates.” The White House always has some incentive to put forth overly optimistic numbers. For one thing, the White House staff generally believe in the wisdom and benefits of the president’s agenda. And if growth rates are boosted and unemployment comes down, it does wonders for budget projections. Tax revenue climbs and spending on programs such as unemployment or Medicaid may dwindle. In recent months, economists’ forecasts for the coming year haven’t changed much. They expect growth for this year of 2.2%, down from 2.4% in the March survey. They place the odds of recession in the next year at just 15%, compared with 20% at this time a year ago. For now, many are waiting to see more detail in Mr. Trump’s agenda and retain doubts about how much he will be able to accomplish. “Infrastructure spending is great, but it has to be paid for and that creates drag at some point,” said Amy Crews Cutts, the chief economist of Equifax. “The proposed tax breaks won’t stimulate the economy nearly enough to pay for themselves let alone fund other new initiatives, which leads to deep cuts in the long run." The survey of 59 economists was conducted from May 5 to May 9. Not every economist answered every question. Quintero and Ginn: Give voters more control of property taxes

Far too many Texans are getting pummeled by property taxes. In 2015, more than 4,100 local governments levied property taxes totaling $52.2 billion, or roughly $1,900 for every man, woman, and child in the Lone Star State. That’s a jump in the tax levy of more than $3 billion from the prior year and almost $12 billion compared with just five years ago. Texans’ property tax bills aren’t just big — they’re also growing quickly. From 2000 to 2015, property tax levies soared statewide by 132 percent. Over the same period, standard economic measures like population growth and inflation increased just 79 percent. These data reinforce what everyone already knows — that Texas’ property tax system is broken and needs an overhaul lest more people lose their homes, businesses, and futures. Fortunately, the problem has not gone unnoticed at the Capitol where legislators are debating a number of different fixes, with one particular solution looking more and more likely. In short, the Legislature looks poised to require cities, counties, and special districts to get permission from voters if already-high property taxes grow too fast in any one year. That focus on voter approval could be a real game-changer. Today, Texans must know and understand what a rollback tax rate is, wait for one of their many local governments to exceed it, and then be ready to quickly obtain a sizable number of signatures to petition for an election. That’s a lot to ask from families who are busy working, raising kids, and generally dealing with life’s challenges. To simplify the process and level the playing field, lawmakers are proposing to reduce the rollback rate by half and require an election to be held automatically if local officials want their budgets to grow by more. By drawing a line in the sand and requiring an election if it’s crossed, Texans can expect future property tax bills to grow more slowly while still allowing local officials an avenue to raise tax revenue if they can make a sufficient case to the public. This not only puts more control in the hands of local voters but also creates a greater level of accountability. Some critics have sought to cast these good government reforms in a bad light by suggesting that it would harm public safety. But as has been documented time-and-again, there’s plenty of waste, fat, and abuse in city budgets that can be better prioritized before we even get close to that point. If the current legislative effort is deficient in any way, it’s that it excludes school district property taxes — a major driver of the problem. However, it’s excluded for a good reason: the school finance system is ridiculously complex and should be addressed separately. Given these structural property tax reforms take effect, they would dramatically alter the local landscape for the better. However, these should only be considered intermediate reforms. The ultimate prosperity- generating reform is to eventually eliminate property taxes, which another bill — HB 1050, which has yet to receive a hearing — proposes to do. Research undergirding the bill shows that this can be done in a revenue-neutral way by enacting a reformed sales tax that broadens the tax base and increases the rate from 8.25 percent to around 11 percent. This wouldn’t just be a tax swap but rather a much more efficient tax system that would contribute to higher incomes and more jobs created, and allow you to actually own your property. Texans want more control over their livelihood instead of giving it to local officials that may unnecessarily raise their taxes to pay for excessive spending. These common sense structural reforms would enhance local control by voters. James Quintero is director of the Center for Local Governance and leads the Think Local Liberty Project at the Texas Public Policy Foundation and Vance Ginn, Ph.D., is an economist in the Center for Fiscal Policy at the Texas Public Policy Foundation, a nonprofit, free-market research institute based in Austin. http://amarillo.com/opinion/opinion-columnist/2017-05-14/quintero-and-ginn-give-voters-more-control-property-taxes?utm_content=buffere7356&utm_medium=social&utm_source=twitter.com&utm_campaign=buffer With sine die on May 29th quickly approaching, the 85th Texas Legislature has much work to do to reduce the size and scope of government. Let us consider the status of the Conservative Texas Budget Coalition’s key legislative priorities in the waning days of session.

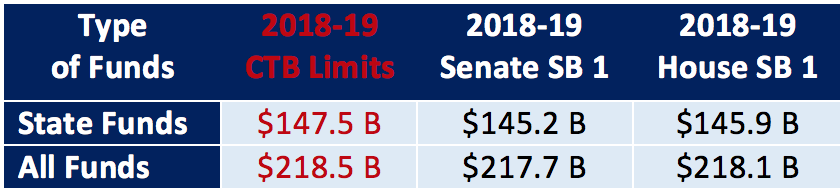

The Conservative Texas Budget (CTB) limits the Legislature’s increase in appropriations for the 2018-19 biennium to no more than population growth plus inflation. As the budget heads to the conference committee for final negotiations before consideration by both chambers, the passed versions of SB 1 by the Senate and the House indicate that they can keep appropriations below the CTB limits.

https://www.texaspolicy.com/content/detail/texas-2018-19-government-budget-comparison |

Vance Ginn, Ph.D.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed