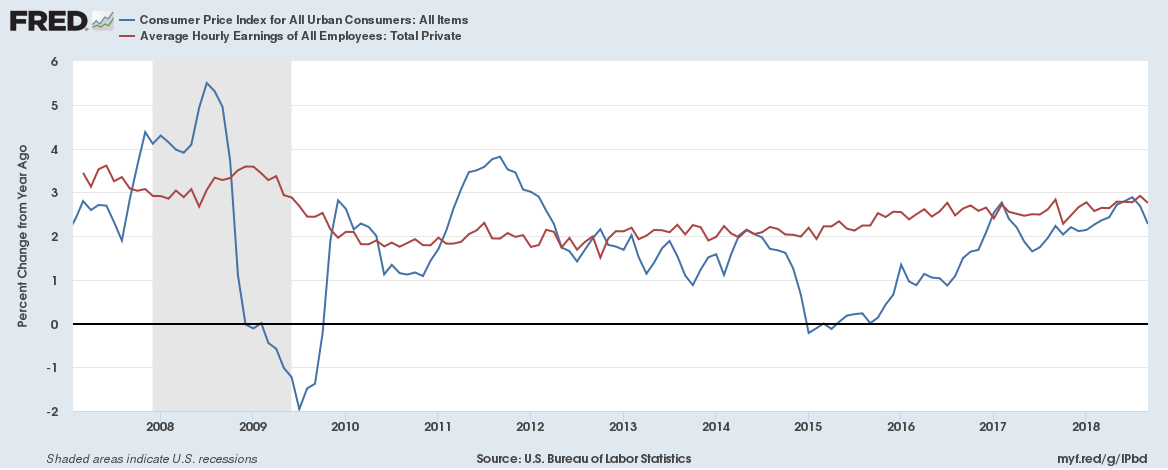

Texas Budget Growth Should Match Texans' Ability to Pay - Not Government's Ability to Grow10/31/2018  Check out the article by economist Stuart Greenfield below. It's interesting how his progressive views, and CPPP—but I repeat myself, has started appropriately considering growth of government spending at no more than population growth and inflation. They just happen to want to use a measure of price inflation for state-local expenditures that grows at a more rapid rate than the more typically used consumer price index, which matches their desire to increase spending and ultimately taxes. Of course, the State-Local Implicit Price Deflator supported by Greenfield in the piece below closely measures prices of goods and services purchased by government with little to no voluntary exchange because they are dominated by government intrusion—both the demand and supply. So, those who want spending to rapidly grow can ratchet spending up to increase demand or regulate the supply to get their desired level of spending, which would most often be MORE! Instead, let’s consider the often recommended measure of population growth plus inflation, which is recommended by the Conservative Texas Budget Coalition for a Conservative Texas Budget. State population increases may require more government provisions. Inflation measured by the Consumer Price Index is closely tied to wage growth (see figure below). The addition of these two measures allow for some level of economies of scale. Thus, the metric of pop+inf gives a relatively good indicator of Texans’ ability to pay for their government instead of how much government can inflate their spending by controlling demand and supply. Given it's Halloween, here’s the spooky part: Governments in Texas already spend too much. In fact, the state's budget is up 7.3% more than population growth plus inflation since 2004. This amounts to $15 billion more in taxpayers dollars spent this two-year budget cycle than if the Legislature had increased the budget by no more than pop+inf since 2004. Or, this means that Texas families of four must spend $1,000 more in state taxes, on average, this year alone. They’ll really go nuts when there is the necessary push for a budget that doesn’t increase at all, or…wait for it…shrinks! Because we all know the government currently spends way too much. Meaning we are taxed way too much! The best measure of government is their spending of our hard-earned tax dollars. Guess that’s too spooky for some. #HappyHalloween #LetPeopleProsper ___________________________________________________________________________ Here is the article by Stuart Greenfield at Quorum Report Greenfield: "How much more can be cut from the Texas budget" In response to the TPPF-led “conservative budget,” economist Stuart Greenfield argues that “what these proposals don’t recognize is that growth in population varies over space and that using the CPI understates the increase in prices local governments experience. But what’s a methodological error among conservative friends?” Before beginning my analysis of state spending over this century, I would like to wish both Ursula Parks, director of the LBB and Mike Reissig, Deputy Comptroller the best as they head off into the joys of having a defined benefit plan pension for the rest of their lives. I would also like to thank them for their willingness to assist my less than sterling efforts at providing readers of the QR analysis on various public policy issues. In Shakespeare’s Most Famous Soliloquy, Hamlet states, “to be or not to be that is the question.” This soliloquy must have been modified by the recently organized Conservative Resolution Underfunding Many Basic Services (CRUMBs), whose motto is “to spend or not to spend, what a stupid question.” Alternatively, the group might have named itself, Conservative Actions Killing Education (CAKE), as in Marie Antoinette’s “let them eat cake.” My humor aside, the Conservative Texas Budget Coalition has offered another conservative budget proposal that would reduce the growth in state expenditures and impose restrictions on local government property tax increases. Their proposed “solution” would over time increase the state’s proportion of expenditures for public education and reduce the growth rate in local property taxes. Who could ask for anything more? From FY00-17, state expenditures grew at an average annual rate of 4.9 percent. In FY18, expenditures grew by 3.5 percent. This rate was less than the rate of increase experienced from FY00-17 in the state’s population (1.8 percent) and the increase in the State-Local Implicit Price Deflator (3.0 percent). So yes, the state’s expenditures for FY18 were conservative. Is a conservative budget the way to ensure continued growth in the Texas economy? That is a point of contention between those advocating for additional state expenditures for public education, health services, et al., and the Conservative Texas Budget Coalition, which advocates for a budget that increases by population and inflation so that taxes can be reduced. Like Julius Caesar’s Commentaries on the Gallic Wars, state expenditures can be divided into three parts, Public Assistance Payments (primarily Medicaid), Public Education, and Other Expenditures. Total All Funds (AF) state expenditures over the 18 fiscal years of this century were $1.6 trillion. Figure 1 shows how these expenditures were divided among the three groups. Other Expenditures (Transportation, Public Safety, Higher Education, Salaries) comprise the largest percentage of state expenditures this century, the trend in this expenditure category has been in decline. As shown in Table 1, Other Expenditures accounted for 45.0 percent of All Funds expenditures in FY00. By FY18, this percentage had declined to 36.9 percent. One should also note that along with a decline in the proportion of All Funds expenditures devoted to other expenditures, the proportion of All Funds expenditures for public education also declined. The proportion of state expenditures devoted to Public Assistance Payments increased from 28.3 percent in FY00 to 40.1 percent in FY18. This increase in proportion was an increase of almost 42 percent. Almost half (49.0 percent) of the increase in state expenditures between FY00 and FY18 was accounted for by the increase in Public Assistance. Only 20.2 percent of the increase in All Funds expenditures were for Public Education. Along with reporting the current/nominal dollars of state expenditures, most analyses take into accountthe growth in both the state’s population growth (1.8 percent/year over the century) and the increase in prices. Unfortunately, most of these analyses use a less precise measure (Consumer Price Index) of how state-local expenditure prices have changed. Over 40 percent of the CPI is comprised of consumer spending for housing. Not even Allen ISD spends 40 percent of its budget on housing its football team. Had the reports used the appropriate measure of State-Local Government prices, the Government Consumption Expenditures and Gross Investment: State and local (implicit price deflator, they would find that the prices state-local governments pay for goods and services are higher than the CPI. One can view how the CPI and State-Local Implicit Price Deflator (S-L IPD) have varied over time. In 2017 the S-L IPD was 16.1 percent greater than the CPI in 2017. Figure 2 shows how the population and the differing price indices affect real expenditures. Using the appropriate price deflator has a significant effect determining real expenditures. As shown in Figure 2, between FY00 and FY18 nominal or current dollar AF expenditures increased by 134.5 percent. When adjusted for the state’s increasing population (1.8 percent per year) and the increase in the CPI (2.1 percent per year) since FY00, the CPI-adjusted AF increase was 17.3 percent. Using the more precise S-L IPD (3.0 percent per year) shows a decrease in real AF state expenditures of 0.4 percent since FY00. So the state spent 0.4 percent less in FY18 than it spent in FY00. Talk about being parsimonious! I would hope that in the future greater concern is shown on using the correct measure for inflation that state and local governments face. According to Fiscal Size-Up 2018-19, 28.5 percent of state All Funds Appropriations for 2018-19 are for purchasing medical services, i.e., Medicaid. In the CPI the relative importance of medical care is 8.7 percent, one-third the importance in the state budget. This difference in importance understates how inflation affects real state-local expenditures over time. Using the incorrect price index affects two other areas that are being debated during this election season. These areas include state expenditures for public education and local government property tax increases. Analyzing state public education expenditures finds different groups using different student counts (ADA, WADA, Enrollment) and different price indices (US CPI or Texas CPI). Again, using either of these price indices understates the increase in costs faced by local school districts. Those advocating for reducing the growth rate in local government tax increases would limit this growth to the growth in population and increase in inflation. To exceed their 2.5-4 percent increase in local property taxes would require voter approval. What these proposals don’t recognize is that growth in population varies over space and that using the CPI understates the increase in prices local governments experience. But what’s a methodological error among conservative friends? Future articles will address these two issues and show how using state population growth, and the CPI will have adverse an impact on the areas of the state that have experienced most of the state’s population growth. The other article will show that using the CPI instead of the S-L IPD understates the “true” decline in the state’s financing of public education. Bet y’all can’t wait for these page-turners. Dr. Stuart Greenfield holds a Ph.D. in economics from the University of Texas. He worked for three Comptrollers of Public Accounts, and since retiring from the state in 2000, Greenfield teaches economics at ACC and UMUC.

0 Comments

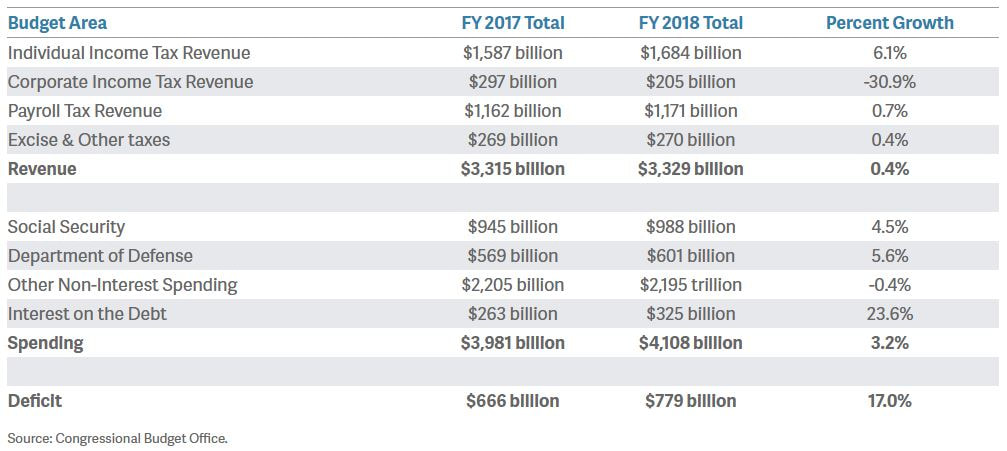

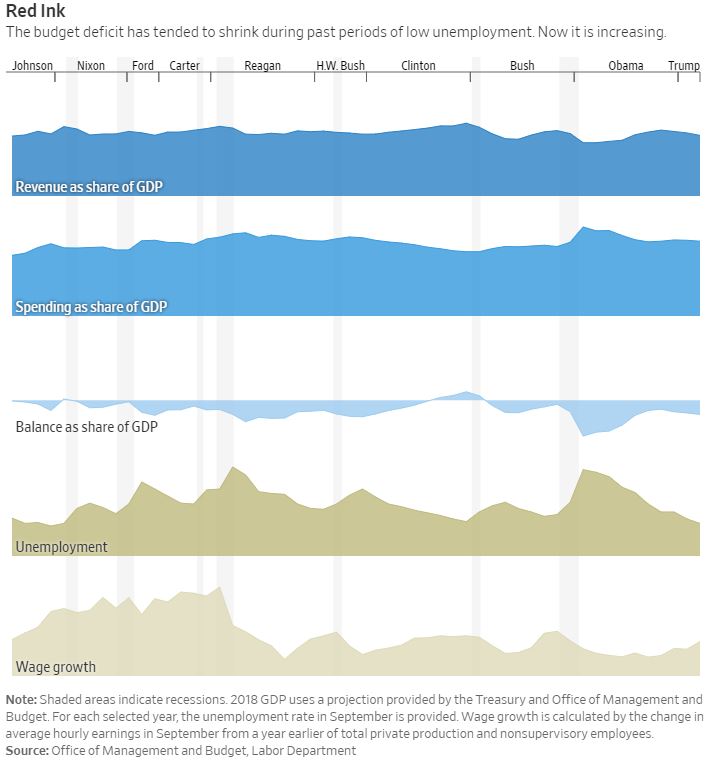

In this Let People Prosper episode, let's discuss Nobel prize-winning economist Paul Krugman's recent concern about the $779 billion budget deficit in FY 2018 under President Trump. Unfortunately, he wasn't worried about the 4 years of more than $1 trillion in deficits under President Obama and he in fact wanted even higher deficit spending. This episode provides a lesson in economics on the aggregate demand-aggregate supply model of how these policies should work in theory but how this mainstream view misses a lot that actually results in my preferred mainstream view of how the economy actually works and the burden higher government spending and resulting deficits put on economic activity and our prosperity.

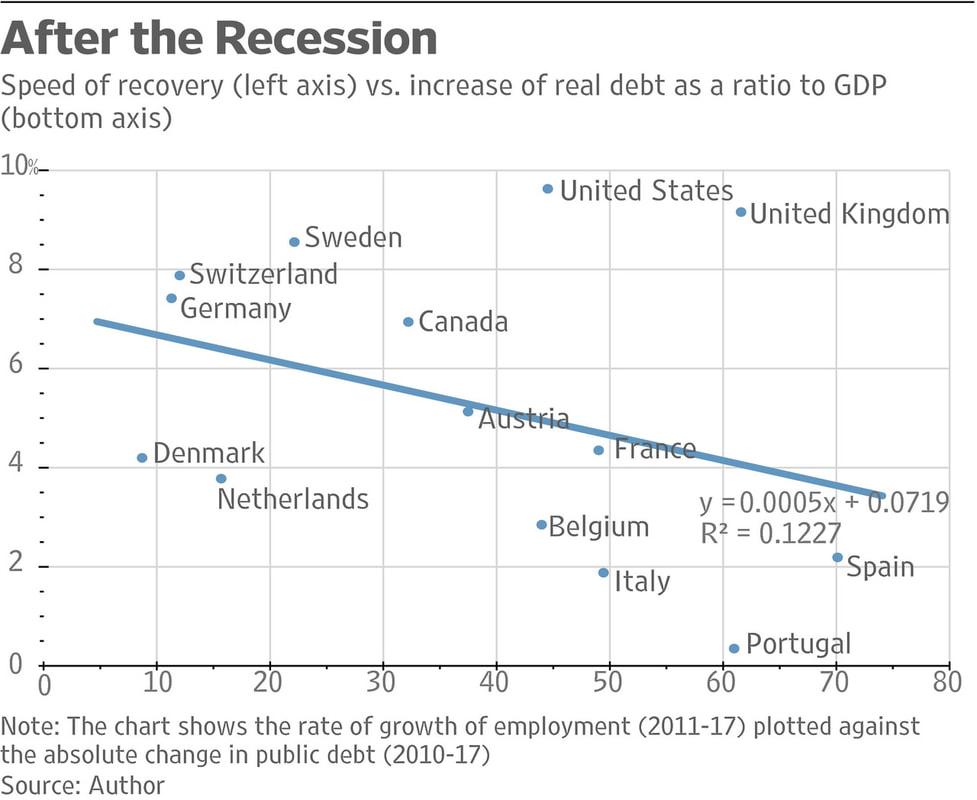

Last Friday the Bureau of Economic Analysis reported that there was an increase of 3.5% in real GDP growth in the third quarter of 2018, indicated that 2018 may be above 3% growth for the first time in more than a decade. This issue along with the rising deficit gave rise to Krugman's tweet below. Here's what Krugman tweeted: "Reaction to the GDP numbers: quarterly growth rates don't mean much. For one thing they fluctuate a lot -- e.g. rapid growth in 2014, signifying little. For another, you can always juice the numbers for a few quarters by running big deficits. What about the long term"? Here was my tweeted response to his tweet that received a lot of attention: "Who is this @paulkrugman who wasn’t worried about budget deficits during #Obama’s 4 years of more than $1 TR deficit but is worried about #Trump’s $779 B? Recall #Krugman was in favor of LARGER deficit spending to “stimulate” the economy under #Obama. Principles matter." I recommend going to my tweeted response and viewing the comments and discussion. It was a rather lively discussion with some good info in there along the way, but much of it was just noise. This recent WSJ opinion piece by Nobel prize-winning economist Edmund Phelps explains the fantasy of fiscal stimulus quite well along with the nice figure below that shows stimulus doesn't correlate with faster economic growth. What we really need for more prosperity is a government that simply sets the rules of the game such that the institutional framework allows for civil society to flourish along with the resulting prosperity for people. Government under presidents of each main party have fallen victim to the "stimulus" argument when in fact it should be about providing the most pro-growth economic environment while running balanced budgets. A good model would be to look at Texas. #LetPeopleProsper In this Let People Prosper episode, let's discuss how the best path to prosperity is capitalism and that starts with a job. The more ways that we can free up the labor market from government barriers to opportunity, such as the minimum wage and occupational licensing, the more prosperity we can all enjoy.

My recent op-ed in the Investor's Business Daily titled "Amazon's Minimum Wage Revelation: It's About Competition, Not Workers" notes the opportunity costs associated with a government-mandated minimum wage compared with a private market decision: "Just as the company's management had the freedom to consider the firm's profitability and outlook in deciding whether to offer the higher wage, other private employers should have the same freedom. Amazon apparently thinks they shouldn't, hence the lobbying for a national mandate. Those lobbying efforts could end up doing even more harm." My recent paper with Dr. Edward Timmons titled "Occupational Licensing: Keeping People Poor" notes the huge cost that many licenses have on people whether they be workers, consumers, or employers. We highlighted this in a recent op-ed: "Between 1993 and 2012, Texas added licensing requirements for 22 low-income occupations. Data from the Texas Department of Licensing and Regulation indicate a 460 percent increase in the number of licenses issued by the department, far surpassing the state’s population growth of 37.5 percent in that period. By making it harder for aspiring workers in Texas to enter the job market, licenses artificially inflate wages — and this means higher prices for the services provided. National estimates suggest that licensing inflates wages of professionals by about 15 percent. And this means consumers pay higher prices. In addition, individuals looking to enter a new field may be prevented from achieving their dreams." For the sake of human flourishing, we should be doing all we can to reduce government barriers to prosperity that are socialist programs like the minimum wage (price of labor control) and occupational licensing (quantity of labor control). #LetPeopleProsper Commentary at McAllen Monitor.

Texas has job openings; Texas has workers willing and eager to fill them. Where’s the disconnect that has resulted in labor shortages in a number of fields? It could be occupational licensing. In many ways, the Texas model of limited government is a blueprint for D.C. and other states. The Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas’ latest reading of Texas’ economy is very positive. Personal income growth in the second quarter of 2018 was 6 percent — the highest in the nation. And the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics recently noted that Texas’ annualized private sector job creation rate of 3.9 percent is about double the national average of 2 percent. Yet there are labor shortages in several fields. There are not enough qualified workers to fill the jobs available. If this problem persists, the ability of Texas to sustain its economic momentum will be restrained. One qualification, which often presents an unnecessary, artificial barrier to employment and prosperity, is occupational licensing. These laws say that willing workers must get a permission slip from state bureaucrats in Austin. To obtain the permission slip, aspiring workers need to pass exams, pay fees, complete minimum levels of education and training, or meet other entry requirements. In 2015, more than 24 percent of workers in Texas had a license. That makes sense for family doctors and surgeons. But hairdressers, auctioneers and (in some states) interior designers? Not so much. We highlight the problems presented by overly burdensome occupational licensing in Texas in a new report published by the Texas Public Policy Foundation. According to the Institute for Justice’s ranking of occupational licensing for states, Texas is right around the middle of the pack — ranked 21st in the burden presented by licenses for low-income occupations. And unfortunately, Texas has mostly been moving in the wrong direction. Between 1993 and 2012, Texas added licensing requirements for 22 low-income occupations. Data from the Texas Department of Licensing and Regulation indicate a 460 percent increase in the number of licenses issued by the department, far surpassing the state’s population growth of 37.5 percent in that period. By making it harder for aspiring workers in Texas to enter the job market, licenses artificially inflate wages — and this means higher prices for the services provided. National estimates suggest that licensing inflates wages of professionals by about 15 percent. And this means consumers pay higher prices. In addition, individuals looking to enter a new field may be prevented from achieving their dreams. Proponents of these licenses claim that it protects the public’s health, safety, or welfare. But the risk of harm presented in these professions varies dramatically. Bad haircuts aren’t fatal. Neither is poor auctioneering or interior decorating. It’s important to note that occupational licensing is often at best used as a signaling device for quality service, but it’s not the only way to regulate a profession. Proponents claim there’s only a binary choice between occupational licensing and no regulation at all, but there are many other ways to protect consumers. Private certification can be used to signal to consumers who provide quality service; auto mechanics use this method quite effectively. The government can perform random safety inspections, as it does in the food services industry. The market can also regulate and provide information to consumers about bad actors via online ratings services like Yelp. Licensing also serves to constrain consumer choice in the market for health care. In Texas, patients have a difficult time seeing nurse practitioners without significant interference from physicians. Consumers should be granted the ability to obtain quality care from highly trained medical professionals like nurse practitioners for basic health care, especially in areas with doctor shortages. The Texas model has achieved some amazing results over the years. We should not let occupational licensing get in the way of Texans achieving their hopes and dreams. Edward Timmons, Ph.D., is director of the Knee Center for the Study of Occupational Regulation at St. Francis University; and Vance Ginn, Ph.D., is director of the Center for Economic Prosperity and senior economist at the Texas Public Policy Foundation. As many across the country argue for an increased federal minimum wage, such as the Fight for $15, Amazon announced on October 2 that they were raising their base pay to $15 per hour. While altering their own business costs is one thing, Amazon also plans to join others in lobbying Congress to mandate a higher minimum wage for Americans.

Amazon’s move to raise its base pay isn’t surprising; the company recently passed the trillion dollar value threshold, second to only Apple. While Amazon may be applauded for raising workers’ pay, its lobbying efforts aren’t as worthy. Just as the company’s management had the freedom to consider the firm’s profitability and outlook in deciding whether to offer the higher wage, other private employers should have the same freedom. Amazon apparently thinks they shouldn’t, hence the lobbying for a national mandate. Those lobbying efforts could end up doing even more harm. Despite the commonly held perception that minimum wage laws reduce income inequality and provide the poor with a better life, the real effects are the opposite. FEWER JOBS, FEWER HOURS Minimum wage laws have proven detrimental by reducing job creation and the total hours worked for low-skilled workers, who are primarily paid the minimum wage and have less than a high school diploma or little work experience. And the laws raise prices for everyone — thus widening income inequality. A labor market without government impediments functions like any other market. Employers and workers negotiate a wage, benefits, hours worked, and other measures of compensation until there’s mutual benefit. If they don’t agree, the worker isn’t hired. This is the same kind of mutually beneficial exchange that occurs when you go to the farmer’s market or department store, and it shouldn’t be any different in the labor market. When this unhampered negotiation is restricted by government barriers such as an arbitrary minimum wage law, there is a misallocation of resources that hurts employers and workers. For example, no matter what the minimum wage is, $15 or $150, the market will correct itself through higher prices and fewer jobs. In other words, the poor will stay poor, as they see their hard-earned dollars able to buy less and find fewer job opportunities. VULNERABLE LOW-SKILL WORKERS Lower-skilled workers are especially vulnerable to the proven job losses caused by federal minimum wage increases because employers who can’t afford the increases in the cost of production simply close up shop, reduce employee hours, or even switch to automation. A recent study on the effects of minimum wage raises in California using data from 1990 to 2016 showed that a 10% increase in the minimum wage could contribute to a 3.4% reduction in employment. Key industries hit hardest are restaurants and retail stores that typically operate on razor-thin profit margins and often hire low-skilled workers and those new to the workforce. And minimum wage laws actually make income inequality worse. As noted from research by the American Action Forum, a large share of the added wage value from minimum wage hikes goes to workers already paid well. For example, McDonald’s has been replacing cashiers with kiosks in many of their locations nationwide. The kiosks are designed, built, and maintained by high-skilled, high-wage workers while cashiers are typically low-skilled, low-wage workers. In other words, jobs are created for computer programmers and robotics experts, while jobs are destroyed for those with fewer skills and less workplace experience. The result is an increase in income inequality. MINIMUM WAGE MISTAKE So why would Amazon lobby for a policy that has such broad negative effects on the economy? Maybe because Amazon is a mammoth corporation that has seen tremendous success in recent years. A higher federal minimum wage would probably not hurt its bottom line much. But Amazon’s competitors might not be so lucky, particularly if they are small businesses just starting out. A higher federal minimum wage could create artificial barriers of entry that would make it easier for Amazon to stay at the top while making it harder for its competitors to succeed. When it comes to wages, what works for one employer doesn’t necessarily work for another. We can applaud Amazon for giving its own workers raises; that doesn’t mean Amazon should be lobbying to demand raises for everyone else’s workers, too. By strengthening the employee-employer relationship through economic freedom — not minimum wage laws — to let people freely negotiate, employees and employers can prosper.

This commentary was published at TribTalk.

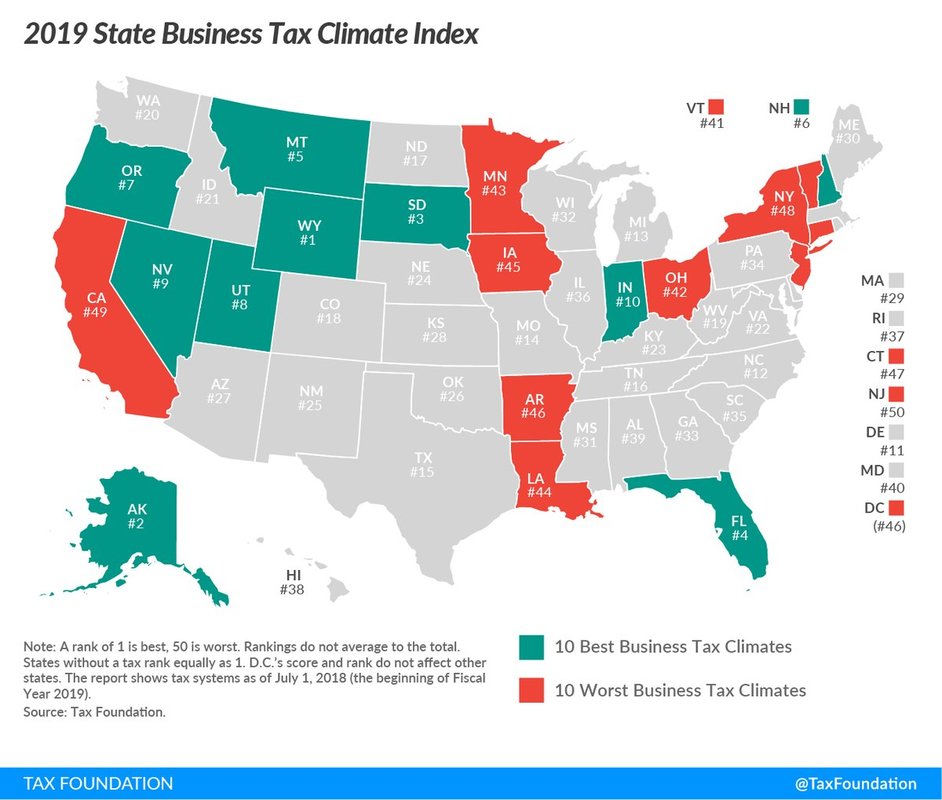

We’ve set some pretty high goals for Texas’ budget for the upcoming biennium. And to achieve them, Texas need to overhaul its arcane and opaque budget-making process. On Sept. 25, the Texas Public Policy Foundation, Heartland Institute, and 16 other member-groups of the Conservative Texas Budget Coalition held a press conference to introduce its legislative priorities for Texas’ 2019 legislative session. These groundbreaking priorities would limit government spending below population growth and inflation and provide enormous tax relief for families across the state. Every odd-numbered year, state lawmakers craft Texas’ two-year budget through the General Appropriations Act, which typically just increases funding to government agencies above their prior biennial levels. If lawmakers suspect that spending increases are unnecessary, the burden of proof is on lawmakers to prove they should spend less. It’s not an ideal process. And it’s made worse by the fact that lawmakers and their constituents often have no idea whether government agencies are spending their money efficiently. When Texas funds departments, it uses a largely unaccountable process known as strategy-based budgeting. As the name suggests, lawmakers designate dollars to agencies to accomplish broad strategies such as providing education, delivering health care, or paving roads. While these objectives are certainly important, the process makes it all but impossible for legislators to know whether government agencies are effectively pursuing these goals, let alone accomplishing them. In fact, many lawmakers have no clue how much spending is dedicated to each agency’s programs, where the money comes from, or whether the money is spent productively. This lack of transparency is a major reason why spending in Texas has exploded over the last 14 years. State spending is up nearly $15 billion more in the current budget than it would be if it had matched increases in population growth and inflation since 2004. This costs the average Texas family of four more than $1,000 in higher taxes each year. And even though many lawmakers wish to tame runaway government spending, they lack the necessary information to determine which programs should be reformed, trimmed or eliminated. One way lawmakers can attain greater fiscal transparency is by replacing Texas’ current strategy-based budget with a program-based budget. Under a program-based budget, legislators and their constituents can track every taxpayer dollar they send to Texas’ various agencies and which specific programs and initiatives they are funding. This will allow both lawmakers and taxpayers to identify misspent funds and root out inefficiencies. Another reform to enhance accountability would be to transition Texas’s finances to a zero-based budgeting process. Under this type of budget process, each agency begins with a budget of zero dollars and must make a clear and compelling case to lawmakers why taxpayers should be spending money on its various programs. They must defend its purpose, its goals and how it spends money to achieve these goals. This increased transparency will allow lawmakers to more effectively scrutinize each agency’s performance and remove programs that fail to serve the public’s needs. Zero-based budgeting has a long history of successfully trimming wasteful spending. In 2003, Texas faced a $10 billion budget shortfall and needed to find a way to balance the budget because of a constitutional balanced budget requirement?. In response, then-Gov. Rick Perry sent every government agency a budget of zero dollars and ordered them to find efficiencies to close the state’s deficit. Not only did these reforms eliminate Texas’ shortfall, they drove agencies to make long-lasting, needed changes to their programs. They cut unnecessary initiatives, streamlined operations and consolidated duplicative programs. Overall, these reforms helped the state balance the budget by reducing spending for the first time since World War II – and not raising taxes. Zero-based budgeting has also allowed lawmakers to eliminate wasteful spending in Georgia, Chicago, and Montgomery County, Pennsylvania. These examples show that proper fiscal transparency and accountability can help Texas’ elected legislators craft a strong conservative Texas budget. Not only would this rein in the excessive size of government, it would help provide an opportunity to deliver substantial tax relief for all Texans. Achieving the Coalition’s priorities would put the Lone Star State on a path to increased, long-term prosperity. In this Let People Prosper episode, I cover my updated presentation that provides information about Texas’ economic and fiscal situation, compares Texas with other large states, and suggests key public policy recommendations to strengthen the Texas model so that it can foster more individual liberty and economic prosperity. Institutions matter as noted by the recent state business tax climate index by the Tax Foundation, which Texas dropped to 15th best nationwide. Texas should increase economic freedom by eliminating unnecessary government barriers to competition to support prosperity. Watch my explanation of this state-level labor report and other videos at my YouTube channel: Vance Ginn Economics. https://www.texaspolicy.com/blog/detail/texas-economic-labor-market-and-fiscal-situation

In this Let People Prosper episode, let's discuss the report released by the U.S. Treasury today that notes the federal budget deficit was $779 billion, an increase of 17%, in fiscal year 2018. Again, the evidence shows that government doesn't have a revenue problem but rather a spending problem.

The largest increase in expenditures was in interest paid on the debt that increased by 23.6% to $325 billion, which is about half of what our taxpayer dollars are used to fund national defense, about one-third of what we pay for Social Security, and about 8% of total federal expenditures. A problem is that interest on the debt will continue to increase at a rapid pace because the national debt looks to continue to grow and the Federal Reserve is expected to raise their targeted federal funds rate, which is currently 2-2.25%. Each dollar spent by the government is funded by either taxes, debt, or inflation. Each of these drain resources from the productive private sector. In other words, each dollar crowds out our ability to satisfy our desires and prosper. So, we must be able to prove without doubt that each dollar is spent more effectively by politicians than by individuals in the private sector. Sure, there are roles for government, but, in my view, the federal government should have three main functions: national defense, justice system, and very few public goods. The total of national defense is just above $600 billion per year, so assuming the rest may run $400 billion per year, that $1 trillion federal budget would be only 25% of the $4.1 trillion spent today. Given a $1 trillion federal budget, the budget surplus would be $2.3 trillion, allowing for substantially lower taxes at every level--preferably one flat rate on final consumption. You'll also notice that tax collections did increase even after the large Trump tax cuts indicating that the robust growth of a dynamic economy supported more revenue, even if it was less than what it could have been otherwise. Moreover, higher tax revenue negates some of the noise by the Congressional Budget Office of a $1.5 trillion deficit over a decade based on a static economic model, but we don't live in a static world and the data today are another revelation of that fact. When we consider these details, the crowd out effect of government spending and interest on the $21.5 trillion debt, which is greater than our country's entire economic output of $20 trillion, is a huge cost to the prosperity of our nation that we must get control over before it's too late. But the cost is even greater than that because the $20 trillion GDP includes government spending, which is about 20% of GDP. If you exclude government spending, which there is good reason because it's a transfer of funds from the private sector, then the national debt would be $21.5 trillion/$16 trillion, or 134%! That's what we are looking at trying to pay back over time and is currently more than $65,000 per American. As Reinhart and Rogoff wrote in their book This Time Is Different, there's likely a threshold when the debt-to-GDP ratio gets too high such that it hinders economic growth. I don't think that threshold is very high and that we are far above it, and moving further above it quickly unless things change. We are seeing the benefits of the tax and regulatory reforms along with the benefits of a long--though relatively weak before recently--expansion, but these benefits will quickly expire if government spending is not restrained, trade barriers continue to be imposed, and the national debt continues to rise. The best path to let people prosper is by getting rid of government barriers to opportunity, so we must reduce government spending. OPINION: CALIFORNIA IS A FAILED MODEL NO MATTER HOW YOU LOOK AT IT

Vance Ginn and Elliott Raia | Director and Research Associate, Center for Economic Prosperity When you have to begin an argument with “depending on how you look at it,” you’re not arguing from a strong position. Yet such has become the answer to the question of, “Is California a good role model?” posed recently in The New York Times. Even its defenders say California’s prosperity is relative. The good news is that those seeking more concrete progress need only to look to the state that inspired the lone star in the upper-left corner of the Golden State’s flag: Texas. While the Texas Model of limited government needs improving, it has already proven to be a more sustainable catalyst for job creation and economic prosperity than in California. Although the idea of limited government may be foreign to many Californians, the Texas Model embraces the principle of reengaging institutions such as family, community, and free markets — institutions that are often undermined by an over-burdensome state. This is not to say the government has no place in Texas; it does. Nor is this to say that those who have fallen through the cracks don’t deserve help in their times of need; they do. Rather, the model revives the notion that government’s primary responsibility is to preserve the liberties of families and individuals, instead of attempting to supplant them. In the case of Texas, this also means allowing employers to operate with freedom and without onerous regulation. The outcome of Texas’ limited government approach is empirically clear. In creating jobs, no one messes with Texas as one in four jobs added nationwide were created in the Lone Star State in the last decade since the Great Recession. But it’s an even longer period of prosperity. Consider that the average unemployment (U3) rate since 2000 was 5.8 percent in Texas compared with 7.7 percent in California and 6.4 percent nationwide. Perhaps more telling of the complete picture is the average underutilization(U6) rate, which includes the unemployed, underemployed, and discouraged workers. Given the data available since 2003, Texas averaged 10.5 percent while California averaged 14.3 percent and the United States averaged 11.6 percent. And poverty is lower in Texas. The Census Bureau’s supplemental poverty index that adjusts for regional costs of living differences and government transfer payments places California’s 19 percent poverty rate the highest nationwide whereas Texas’ rate of 14.7 percent is near the U.S. average of 14.1 percent. With a relatively light tax burden on employers in Texas compared with California, Texas’ employers have the freedom to innovate and grow. Although the current level of taxation is a stark departure from West Coast philosophy, Texans already see where improvement can be made as efforts to corral skyrocketing property taxes are underway to maintain their economic canter. While taxes play a role in overall government intrusion, burdensome regulations do, too. The Texas Model, while still not free of all unnecessary regulation and corporate welfare, places more faith and decision-making in markets, where individuals — not politicians — decide the best way to satisfy their desires. Consider the energy industry in Texas. While the state has yet to completely eliminate its wind subsidies, it has, in general, taken a more moderated position on industry regulation than the California model. Instead of coercing consumers towards a source of energy favored by bureaucrats and politicians, Texas strengthens its power generation, reliability and cost efficiency by allowing consumers to access a wide energy portfolio. As a result, Texans pay half the price for their electricity than their Californian counterparts, while also not having to contend with potential rolling blackouts whenever the sun doesn’t shine and the wind doesn’t blow. While energy is just one example, the California Model’s policies highlight why the state has nearly 20 percent of its population in poverty. No matter how well-intentioned, when government entangles itself in the lives of individuals and tries to supersede other institutions that may be more effective, tribulation soon follows. Will the nation follow California down a road to serfdom, or, more recently, follow Texas down a road to liberty? That question remains undecided. But if the mass migration of individuals and businesses out of California and into Texas is any indication, the trend is clear that institutions matter. When institutions in civil society are strengthened by limiting government, people prosper. Vance Ginn, Ph.D., is director of the Center for Economic Prosperity and senior economist. Elliott Raia is a research associate. Both work at the Texas Public Policy Foundation. Read the Foundation’s latest report for more. In this Let People Prosper episode, I take a little more time than usual (hope you'll watch the entire episode) to share what economists like Adam Smith, David Ricardo, Daniel Hamermesh, Paul Krugman, and Milton Friedman said about international trade.

In summary, people prosper from trade (see my paper here) and I'm cautiously optimistic about the revised version of NAFTA which is now being called the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), especially with the reduction of some foreign trade uncertainty, but have many reservations of the toll the increased trade barriers put on the auto sector will have on Americans. The legislatures of each of these countries will not have 60 days to review and vote. Let us not forget the benefits of free trade and find ways to reduce trade barriers instead of erecting more. #LetPeopleProsper |

Vance Ginn, Ph.D.

|

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed