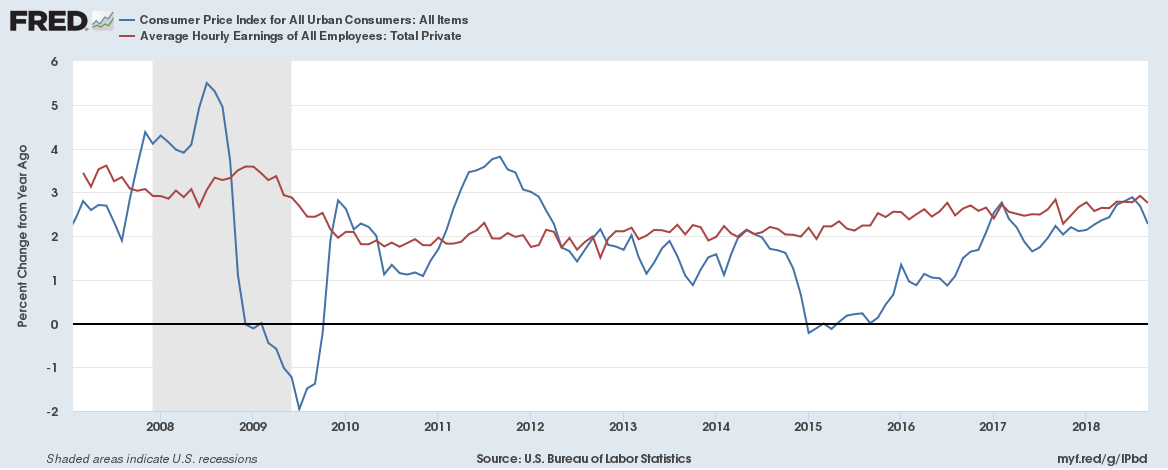

Texas Budget Growth Should Match Texans' Ability to Pay - Not Government's Ability to Grow10/31/2018  Check out the article by economist Stuart Greenfield below. It's interesting how his progressive views, and CPPP—but I repeat myself, has started appropriately considering growth of government spending at no more than population growth and inflation. They just happen to want to use a measure of price inflation for state-local expenditures that grows at a more rapid rate than the more typically used consumer price index, which matches their desire to increase spending and ultimately taxes. Of course, the State-Local Implicit Price Deflator supported by Greenfield in the piece below closely measures prices of goods and services purchased by government with little to no voluntary exchange because they are dominated by government intrusion—both the demand and supply. So, those who want spending to rapidly grow can ratchet spending up to increase demand or regulate the supply to get their desired level of spending, which would most often be MORE! Instead, let’s consider the often recommended measure of population growth plus inflation, which is recommended by the Conservative Texas Budget Coalition for a Conservative Texas Budget. State population increases may require more government provisions. Inflation measured by the Consumer Price Index is closely tied to wage growth (see figure below). The addition of these two measures allow for some level of economies of scale. Thus, the metric of pop+inf gives a relatively good indicator of Texans’ ability to pay for their government instead of how much government can inflate their spending by controlling demand and supply. Given it's Halloween, here’s the spooky part: Governments in Texas already spend too much. In fact, the state's budget is up 7.3% more than population growth plus inflation since 2004. This amounts to $15 billion more in taxpayers dollars spent this two-year budget cycle than if the Legislature had increased the budget by no more than pop+inf since 2004. Or, this means that Texas families of four must spend $1,000 more in state taxes, on average, this year alone. They’ll really go nuts when there is the necessary push for a budget that doesn’t increase at all, or…wait for it…shrinks! Because we all know the government currently spends way too much. Meaning we are taxed way too much! The best measure of government is their spending of our hard-earned tax dollars. Guess that’s too spooky for some. #HappyHalloween #LetPeopleProsper ___________________________________________________________________________ Here is the article by Stuart Greenfield at Quorum Report Greenfield: "How much more can be cut from the Texas budget" In response to the TPPF-led “conservative budget,” economist Stuart Greenfield argues that “what these proposals don’t recognize is that growth in population varies over space and that using the CPI understates the increase in prices local governments experience. But what’s a methodological error among conservative friends?” Before beginning my analysis of state spending over this century, I would like to wish both Ursula Parks, director of the LBB and Mike Reissig, Deputy Comptroller the best as they head off into the joys of having a defined benefit plan pension for the rest of their lives. I would also like to thank them for their willingness to assist my less than sterling efforts at providing readers of the QR analysis on various public policy issues. In Shakespeare’s Most Famous Soliloquy, Hamlet states, “to be or not to be that is the question.” This soliloquy must have been modified by the recently organized Conservative Resolution Underfunding Many Basic Services (CRUMBs), whose motto is “to spend or not to spend, what a stupid question.” Alternatively, the group might have named itself, Conservative Actions Killing Education (CAKE), as in Marie Antoinette’s “let them eat cake.” My humor aside, the Conservative Texas Budget Coalition has offered another conservative budget proposal that would reduce the growth in state expenditures and impose restrictions on local government property tax increases. Their proposed “solution” would over time increase the state’s proportion of expenditures for public education and reduce the growth rate in local property taxes. Who could ask for anything more? From FY00-17, state expenditures grew at an average annual rate of 4.9 percent. In FY18, expenditures grew by 3.5 percent. This rate was less than the rate of increase experienced from FY00-17 in the state’s population (1.8 percent) and the increase in the State-Local Implicit Price Deflator (3.0 percent). So yes, the state’s expenditures for FY18 were conservative. Is a conservative budget the way to ensure continued growth in the Texas economy? That is a point of contention between those advocating for additional state expenditures for public education, health services, et al., and the Conservative Texas Budget Coalition, which advocates for a budget that increases by population and inflation so that taxes can be reduced. Like Julius Caesar’s Commentaries on the Gallic Wars, state expenditures can be divided into three parts, Public Assistance Payments (primarily Medicaid), Public Education, and Other Expenditures. Total All Funds (AF) state expenditures over the 18 fiscal years of this century were $1.6 trillion. Figure 1 shows how these expenditures were divided among the three groups. Other Expenditures (Transportation, Public Safety, Higher Education, Salaries) comprise the largest percentage of state expenditures this century, the trend in this expenditure category has been in decline. As shown in Table 1, Other Expenditures accounted for 45.0 percent of All Funds expenditures in FY00. By FY18, this percentage had declined to 36.9 percent. One should also note that along with a decline in the proportion of All Funds expenditures devoted to other expenditures, the proportion of All Funds expenditures for public education also declined. The proportion of state expenditures devoted to Public Assistance Payments increased from 28.3 percent in FY00 to 40.1 percent in FY18. This increase in proportion was an increase of almost 42 percent. Almost half (49.0 percent) of the increase in state expenditures between FY00 and FY18 was accounted for by the increase in Public Assistance. Only 20.2 percent of the increase in All Funds expenditures were for Public Education. Along with reporting the current/nominal dollars of state expenditures, most analyses take into accountthe growth in both the state’s population growth (1.8 percent/year over the century) and the increase in prices. Unfortunately, most of these analyses use a less precise measure (Consumer Price Index) of how state-local expenditure prices have changed. Over 40 percent of the CPI is comprised of consumer spending for housing. Not even Allen ISD spends 40 percent of its budget on housing its football team. Had the reports used the appropriate measure of State-Local Government prices, the Government Consumption Expenditures and Gross Investment: State and local (implicit price deflator, they would find that the prices state-local governments pay for goods and services are higher than the CPI. One can view how the CPI and State-Local Implicit Price Deflator (S-L IPD) have varied over time. In 2017 the S-L IPD was 16.1 percent greater than the CPI in 2017. Figure 2 shows how the population and the differing price indices affect real expenditures. Using the appropriate price deflator has a significant effect determining real expenditures. As shown in Figure 2, between FY00 and FY18 nominal or current dollar AF expenditures increased by 134.5 percent. When adjusted for the state’s increasing population (1.8 percent per year) and the increase in the CPI (2.1 percent per year) since FY00, the CPI-adjusted AF increase was 17.3 percent. Using the more precise S-L IPD (3.0 percent per year) shows a decrease in real AF state expenditures of 0.4 percent since FY00. So the state spent 0.4 percent less in FY18 than it spent in FY00. Talk about being parsimonious! I would hope that in the future greater concern is shown on using the correct measure for inflation that state and local governments face. According to Fiscal Size-Up 2018-19, 28.5 percent of state All Funds Appropriations for 2018-19 are for purchasing medical services, i.e., Medicaid. In the CPI the relative importance of medical care is 8.7 percent, one-third the importance in the state budget. This difference in importance understates how inflation affects real state-local expenditures over time. Using the incorrect price index affects two other areas that are being debated during this election season. These areas include state expenditures for public education and local government property tax increases. Analyzing state public education expenditures finds different groups using different student counts (ADA, WADA, Enrollment) and different price indices (US CPI or Texas CPI). Again, using either of these price indices understates the increase in costs faced by local school districts. Those advocating for reducing the growth rate in local government tax increases would limit this growth to the growth in population and increase in inflation. To exceed their 2.5-4 percent increase in local property taxes would require voter approval. What these proposals don’t recognize is that growth in population varies over space and that using the CPI understates the increase in prices local governments experience. But what’s a methodological error among conservative friends? Future articles will address these two issues and show how using state population growth, and the CPI will have adverse an impact on the areas of the state that have experienced most of the state’s population growth. The other article will show that using the CPI instead of the S-L IPD understates the “true” decline in the state’s financing of public education. Bet y’all can’t wait for these page-turners. Dr. Stuart Greenfield holds a Ph.D. in economics from the University of Texas. He worked for three Comptrollers of Public Accounts, and since retiring from the state in 2000, Greenfield teaches economics at ACC and UMUC.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Vance Ginn, Ph.D.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed