How the Fed Destroys the Economy with Dr. Robert Gmeiner | Let People Prosper Show Ep. 1016/17/2024 Join me for Episode 101 of the Let People Prosper Show, where I discuss with the insightful Dr. Robert Gmeiner how the Federal Reserve's actions affect our economy. Dr. Gmeiner is an Assistant Professor of Financial Economics at Methodist University.

We Explore: 📉 How the Federal Reserve distorts market activity and creates inflation. 📊 How the Fed’s actions harm economic growth and manipulate interest rates. 💡 Why fiscal policy is not the primary cause of inflation. 🔮 How you should plan to deal with elevated inflation for years to come. Like, subscribe, and share the Let People Prosper Show, and visit vanceginn.substack.com for more insights from me, my research, and ways to invite me on your show, give a speech, and more.

1 Comment

In “This Week’s Economy” episode 55, I discuss the following and more in 11 minutes:

Originally this article with my quotes ran by KTRH News in Houston.

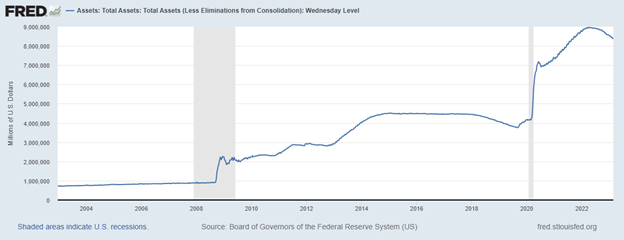

Under the Presidency of Woodrow Wilson in 1913, the Federal Reserve was born. The goal of it was simple, to help avert depressions and inflation, while preventing wealthy Americans from controlling financial markets at lower class expense. For the majority of its lifespan, it has sat mostly unimpactful, until the 1980s. With inflation raging out of control, then-Fed Reserve Chairman Paul Volker gave us tough love, and raised the rates along with restricting the money supply. This led to some hard time initially, especially within the first 6 months, but it eventually helped quell inflationary pressures on the economy, and we transitioned into the economic prosperity of the Ronald Reagan days. But in the last two decades, the Fed has gradually sought to destroy the American dollar, releasing endless money into the economy all while their balance sheet balloons to outrageous levels. It has culminated now in lower-to-middle class Americans struggling to make ends meet and buy basic necessities. Economist Vance Ginn says the many 'band aids' that the Fed has put on the economy, like monetizing debt, have hurt Americans more than ever. "Everyone's cost of living has dramatically increased...and the Fed has directly contributed to that by how much they have manipulated interest rates through their balance sheet, and by increasing the money supply," he says. For the longest time, the Fed kept interest rates has artificially kept he rates low to finance the dramatic government overspending. Then when the pandemic hit in 2020, the Fed created trillions to give away in stimulus checks, and to try and boost the economy, which has now essentially ruined it. As mentioned above, the old chairman Paul Volker's ways were about creating a brighter long-term future, instead of short-term fixes. That, according to Ginn, is what we desperately need again. "We need that style...he used to dramatically cut the money supply, which helped heal the pressures on the economy...so far, current Chairman Jerome Powell has not wanted to do that," he says. "Sometimes you need to have short term pains for long term gains." Current chairman Jerome Powell was a Donald Trump appointee, but the former President has since grown weary of Powell, criticizing him more and more. Trump has made a living on the campaign trail bashing the Biden economy, which he has vowed to fix if he wins office again. But to fix the situation might mean taking a hard look at Powell, and potentially replacing him. "We need someone who understand the economy, and the influence the Fed has on our lives," he says. "We need to make sure there is a sustainable path forward...that will be pivotal for the first part of a Trump Administration in 2025." As for who Trump would tab as a new Chairman is anyone's guess. But the parameters for what is needed are there. "In order to have the Fed come in and make those needed major changes...you have to give someone the leeway to do that, whether Trump like it or not," Ginn says. Trump would very much not like having to cause financial pain for Americans, considering how much he prides himself on winning at all costs. But he may not have a choice. "I think he will be able to sell it to the people though...he can just blame it on Biden," he says. But until then, as with just about every other aspect of our lives, the Biden Administration will continue keeping their thumb down on lower to middle class Americans. Originally published at AIER.

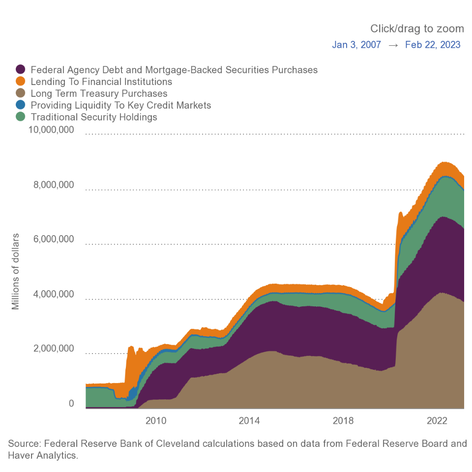

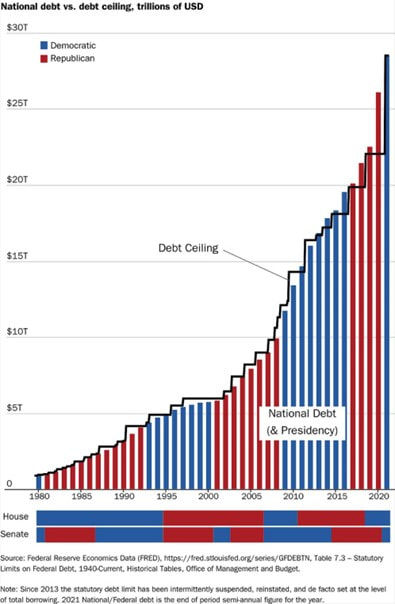

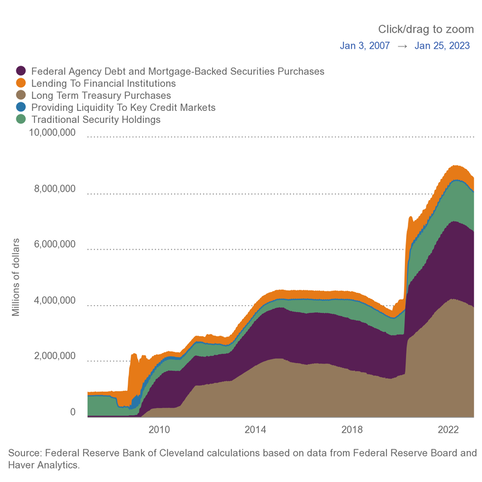

ohn Cochrane’s The Fiscal Theory of the Price Level examines the relationship between fiscal policy and inflation, which many consider to be the increase in the price level of a basket of goods and services. An influential and accomplished economist at the Hoover Institution, Cochrane is one of the most forward-thinking economists today. His approach challenges conventional wisdom and presents a compelling case for reevaluating our understanding of the economy. I learned much from reading the book and while interviewing him about it on my Let People Prosper Show podcast. I highly recommend reading this extensive book, though I have reservations about fiscal policy trumping monetary policy when considering the influence on inflation. Cochrane begins by laying out the foundational principles of his theory. He emphasizes the roles of government debt, taxes, and inflation expectations on prices. He argues that traditional economic models, which focus primarily on the role of central banks in controlling inflation through monetary policy, such as those by Milton Friedman, overlook the substantial effect of fiscal variables on prices. By uniquely integrating fiscal considerations and the public’s expectations about those factors into economic analysis, Cochrane aims to provide a more robust framework for understanding and predicting inflationary trends. He delves into various theoretical and empirical aspects of fiscal theory, drawing on a wide range of literature and evidence to support his arguments. He explores the implications of government budget constraints, the role of Ricardian equivalence that assumes a balanced budget over time, and the potential limitations of conventional monetary tools in controlling inflationary pressures. His thorough examination of these issues provides readers with a comprehensive understanding of the complexities of studying the relationship between fiscal policy and inflation. Cochrane’s arguments are persuasive and well-supported, but some aspects of his analysis warrant scrutiny. One area of contention is Cochrane’s emphasis on the primacy of fiscal policy in driving inflationary dynamics, particularly his assertion that the Federal Reserve plays a secondary role compared to Congress in shaping inflation outcomes. While Cochrane makes a compelling case for the importance of fiscal variables, the penultimate creator of inflation is the Fed when it creates more money than the goods and services produced. Milton Friedman, who extensively studied the role of the Fed in economic activity and inflation, said: “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon. It is a result of a greater increase in the quantity of money than in the output of goods and services which is available for spending.” The Fed controls what’s called “high-powered money” of various assets on its balance sheet. These assets include mostly Treasury securities from the tens of trillions of dollars in debt issued by the federal government. It also includes mortgage-backed securities, lending to financial institutions, federal agency debt, and other lending facilities. I agree with Cochrane that federal deficits give ammunition to the Fed when it purchases Treasury debt, grows high-powered money, contributes to more money chasing too few goods and services, and results in inflation. But other assets on the Fed’s balance sheet also matter, especially since the Great Financial Crisis in 2008 when the Fed started quantitative easing. Cochrane’s framework overlooks the significant role of monetary policy in influencing inflation expectations and shaping the broader economic environment. While fiscal policy can play a role in determining long-term inflation trends, as the debt distorts interest rates in the market, the Fed’s control of the money supply to target the federal funds rate and influence other rates along the yield curve remains a potent tool for managing expectations. While we should challenge Congress to adopt a fiscal rule for sustainable budgets to relieve excessive spending that drives up the national debt, this does not undermine the source of inflation: the Fed. But if Congress could balance its budget, which hasn’t happened since 2001, it would remove a bullet the Fed could shoot at the economy. In other words, a sustainable fiscal policy, wherein Congress passes balanced budgets by limiting government spending — the ultimate burden of government and the source of budget deficits — would help control inflation. While this could mitigate the assets available for the Fed to add to high-powered money, it would not solve the inflation problem because of many other available assets. Another issue that arises from considering fiscal policy the prime mover of inflation is how it works in practice. Fiscal policy is not directly expansionary or contractionary, as it is just taking funds from some people to give to others, with many of the takers being politicians and bureaucrats in government. These actions move money around in the economy without increasing productive activity that creates goods and services. There are roles for the federal, state, and local governments, but those should be limited to those outlined in constitutions. If Congress would abide by the Constitution, whereby it funded only limited government instead of the bloated federal government today, then fiscal policy would not be so burdensome. Fiscal policy would also not fall into the Keynesian trap of trying to “stabilize economic activity,” as the only thing that governments typically stimulate is more government because of the created failures due to the limited knowledge and rent seeking by politicians and bureaucrats. The underlying problem is usually government failures that cannot be resolved by more government. When Congress returns to its limited, constitutional roles, the federal budget will be drastically cut, resulting in lower taxes and opportunities to pay down and retire the national debt. This would also help reduce the massive distortions throughout the economy from government spending, taxes, and regulations. It would also decrease the Fed’s influence on the economy, but not entirely because of the other assets available for its disposal. The Fed also distorts economic activity through its ability to influence each stage of the production process with the assets on its balance sheet and its effect on interest rates. When the Fed purchases Treasury debt and increases high-powered money, the new money does not go to everyone simultaneously. Instead, the money trickles down from the financial sector to other sectors based on credit availability and other factors, in what is called the Cantillon effect. The manipulation of different markets throughout the production process of goods by the new money and the influence the purchase of assets by the Fed has on interest rates create boom and bust cycles. There is ample evidence about these economic steps, especially from the Austrian business cycle theory. Fiscal policy influences many steps in the production process through subsidies, tax breaks, and regulations, which hinder the voluntary production of individual goods and services through a well-functioning price system. But Congress cannot increase the money supply, which only the Fed can do, nor influence the general price level nor the resulting inflation. All things considered, Cochrane’s comprehensive exploration of fiscal theory and extensive analysis of its implications for the price level riveted me. His methodical dissection of economic concepts and pragmatic approach to examining fiscal policy offered a fresh perspective on economic dynamics. In conclusion, the Fiscal Theory of the Price Level offers a valuable contribution to the ongoing debate surrounding the determinants of inflation and the role of fiscal policy in the economy. While I’m sympathetic to Cochrane’s arguments, it is essential to recognize the importance of a central bank’s monetary policy in causing inflation through its balance sheet. Additionally, we should acknowledge the distortions caused by government policy, whether fiscal or monetary, and recognize the secondary role of fiscal policy compared to monetary policy in addressing inflationary pressures. To ensure sound economic outcomes, it is imperative to establish strong fiscal and monetary rules that provide an institutional framework limiting the burdens of government actions on our lives and livelihoods. Despite my dissent on the emphasis placed on fiscal policy’s role in inflation, the book’s productive discourse on the delicate dynamics of key economic elements make this an important contribution to inflation studies. While the latest “strong” US jobs report and “cooling” CPI inflation have been touted as promising, a closer look reveals more complexity, and many American families continue to bear the brunt of DC’s failures over the last three-plus years.

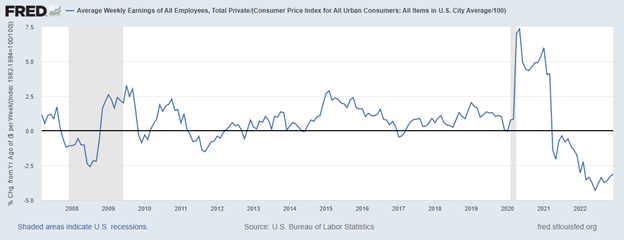

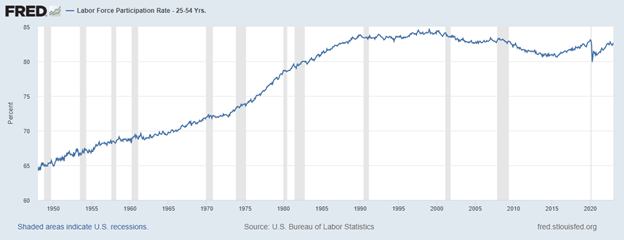

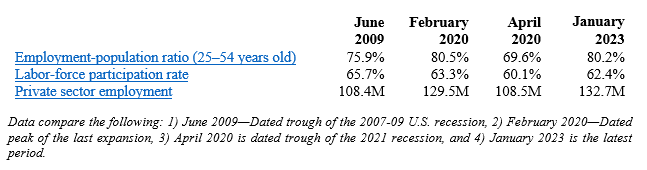

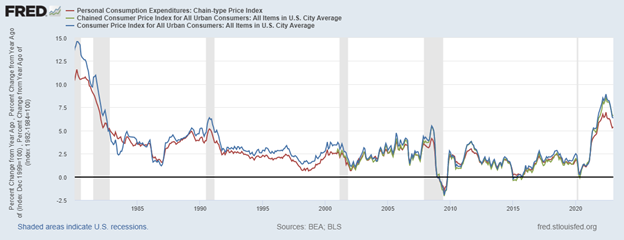

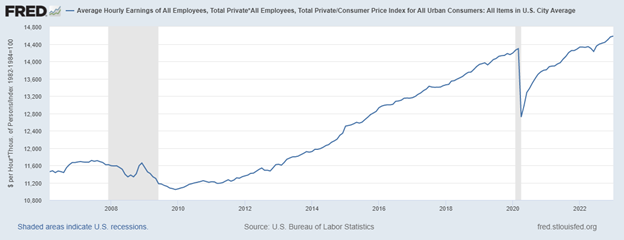

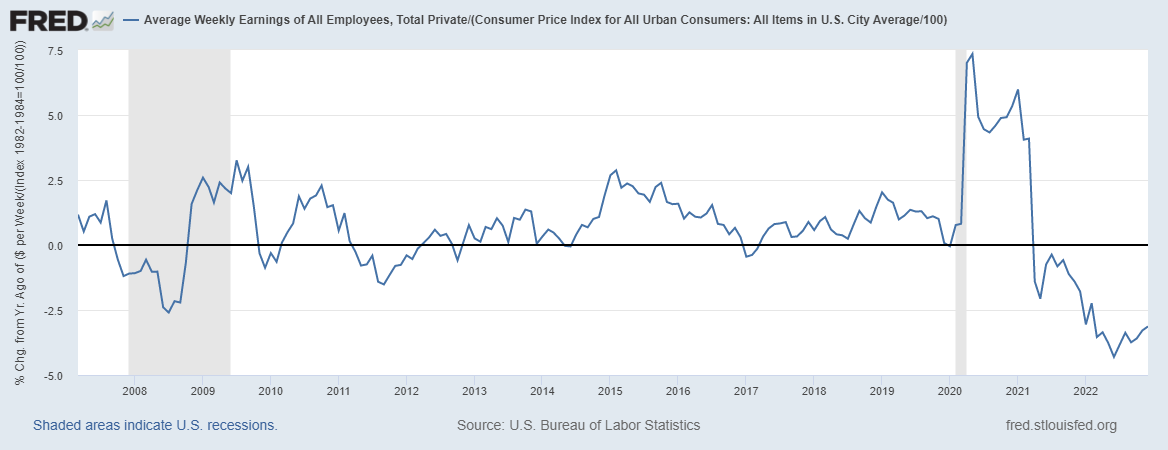

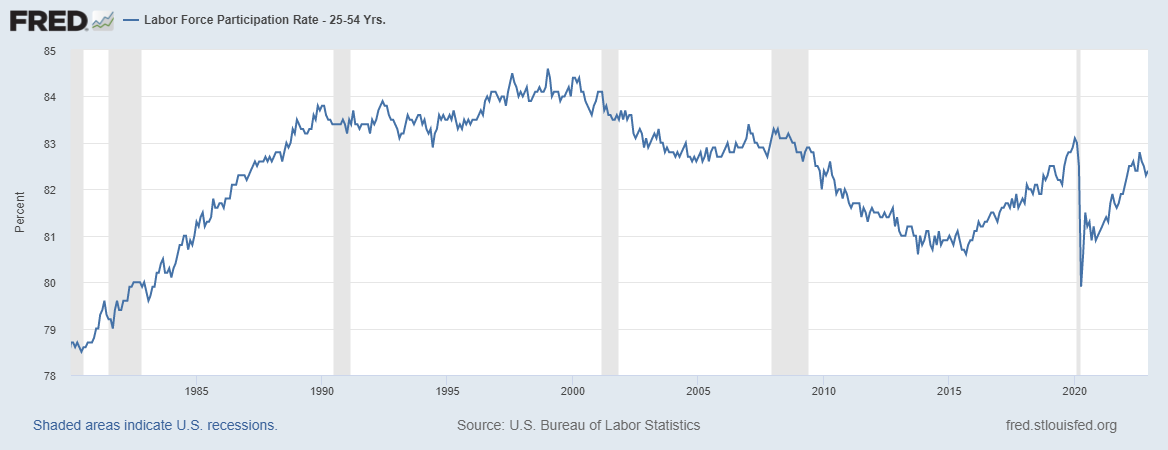

The payroll survey’s net gain of 336,000 non-farm jobs is a popular headline, as the figure nearly doubled expectations. But the household survey, a second crucial report by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, shows that only 84,000 jobs were added in September. Meanwhile, the unemployment rate stayed at 3.8 percent, which would be much higher if more people were looking for work. Let’s consider the labor force participation rate of 62.8 percent to double-check the headlines. If this rate were 63.3 percent, as it was in February 2020, there would be 1.4 million more people in the labor force. If they are all unemployed, today’s unemployment rate would be nearly 5 percent, which is substantially higher than the touted 3.8 percent rate. There have also been substantial revisions to the non-farm jobs report in recent months because of volatile data used for seasonal adjustments since the shutdowns, which makes much of it “garbage in, garbage out.” There were, for example, an additional 119,000 jobs added over just July and August than what was initially reported, giving us reason for pause with all of these reports. In short, this volatility in the job market data makes it challenging to discern actual trends, especially when Americans continue to be concerned about the economy. On top of a fickle job market, the latest consumer price index (CPI) sits at 3.7 percent over the past year, while the core inflation, which excludes food and energy, is 4.1 percent. This core inflation rate is double the Federal Reserve’s average inflation rate target and doesn’t show any signs of reverting to 2 percent any time soon. This problem was created by the Fed’s bloated balance sheet, which results from its willingness to help finance the federal budget deficits caused by excessive government spending. Until Congress reins in government spending and money printing, inflation will strain household budgets. Also, real (inflation-adjusted) average weekly earnings dropped by 0.2 percent over the past year, and the average family’s real income has suffered a significant blow, with a decline of more than $7,000 since the start of 2021. These financial setbacks are not coincidental. They are the direct result of the progressive policies of the Biden Administration, the Federal Reserve’s bloated balance sheet, and Congress’s habit of excessive spending. If we want to understand the true state of our economy, we should pay more attention to the Fed’s balance sheet, which remains a crucial indicator of inflationary pressures. This is why I was never on team “transitory inflation.” Even a relatively superficial understanding of the work of Milton Friedman, Friedrich Hayek, and John Taylor has indicated from the start that we would face persistent inflation. Sure, supply-side factors contributed to higher prices in some markets, as did supply chain bottlenecks. But those are short-term fluctuations that don’t tell the entire story of reduced purchasing power for everyone over a longer period, which is a story of failed public policy on top of the failed shutdowns during the pandemic. The explanation is pretty straightforward. There was a sudden halt in the economy due to pandemic shutdowns that distorted many exchanges throughout the marketplace. The federal government then sent out redistributed money to individuals and employers so they wouldn’t have to fret too much during a stressful time. This propped up many Americans, creating any number of zombie firms, zombie workers, and a debt-fueled zombie economy. But this alone wouldn’t explain the inflation, as increased government spending doesn’t stimulate anything other than more government and some specific markets. Next, the Fed more than doubled its balance sheet, increasing its assets from $4 trillion to $9 trillion. This doesn’t lead to long-term economic growth, but it does contribute to many market distortions and inflation across the economy. Much of this money stays in the hands of the banks, mortgage companies, and others at the upper part of the income spectrum. Only then does some of it spread further, in a process known as the Cantillon effect. The problem is not only a propped-up economy with multiple asset bubbles, but reduced purchasing power that punishes lower-income families the most. Few, if any, of the positives from more money in circulation goes to these families. Instead, they have seen whatever savings they had dwindle. To achieve a more stable and prosperous economic future, we must strike a balance between sound fiscal and monetary policies and curb excessive government spending and money printing. This will only begin to happen when we have rules that control discretionary policies by the administration, Congress, and the Fed. While headline jobs and inflation data might suggest a strong economic recovery, digging just a little deeper into the data shows a weak economy with major challenges. It’s time for policymakers to take a hard look at the factors contributing to these economic woes and adopt prudent policies that address the root causes of stagflation. Originally published by AIER. I hope you enjoy the 31st “This Week’s Economy” episode! Please subscribe to my newsletter if you haven’t already, and subscribe to my podcast wherever you get yours. I would appreciate it if you would also rate and review my podcast! Today, I cover:

Check out the highlights from my recent segment on Fox Business. Former Office of Management and Budget chief economist Vance Ginn and Slatestone Wealth chief market strategist Kenny Polcari analyze how the Middle East conflict and House speaker standstill impact markets.

Full segment on Fox Business here. Americans say the economy is the most important problem facing the country. But major headlines covering the latest jobs report for August do their best to downplay this concern. The New York Times’ headline covering the news was, “August Jobs Report: U.S. Jobs Growth Forges On,” but the economic reality is far less cheerful.

Sure, the jobs report beat the consensus estimate by economists. But that high-level look at the data fails to address underlying issues keenly felt by many Americans that are apparent with more scrutiny. And these problems won’t be over unless policies out of D.C. substantially and quickly improve. Last month, 187,000 jobs were added, according to the payroll survey, compared with the anticipated 170,000. But the jobs added in the prior two months were revised lower by a cumulative 110,000 jobs, bringing the net jobs added in August to just 77,000. This extends an ongoing trend of downward revisions over the last several months. According to the household survey, the unemployment rate, a weak indicator of the labor market’s strength, jumped substantially from 3.5% to 3.8%. Coupled with news of slow wage growth of just 0.2% last month, there is growing concern among Americans trying to make ends meet. We know the higher unemployment rate isn’t from too few jobs available. The number of job openings has been nearly double that of those unemployed for a long time, though decreasing quickly. Instead, the higher rate suggests a sluggish economy in which there are more unemployed or ghost job openings from companies that do not intend to hire but want to gauge interest and competition. There is some good news. The labor force increased by 736,000, which raised the participation rate to 62.8% in August. This is the highest rate since February 2020, just before the shutdowns in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. More people entering the labor force and higher participation rates appear promising. However, the increase in the labor force was a combination of 222,000 more people employed, with the other 514,000 people becoming unemployed. And diving deeper, 4.2 million more adults remain not in the labor force compared with February 2020. Many of these individuals have been unemployed for years, so obtaining employment could be difficult due to a lack of productivity signals in their resume on top of employers dealing with a stagnant economy. The rise in the unemployment rate, lackluster wage growth, and the possibility of unfilled job openings all point to a weak labor market. Add in ongoing stagflation, as too-high inflation continues, and Americans are rightly concerned about the future. Some blame the Federal Reserve for this weakness because of its fight to bring down inflation after creating it. However, Milton Friedman debunked this tradeoff between lower inflation and a higher unemployment rate decades ago. Specifically, there’s no long-run tradeoff between the two, so the Fed must focus on the single mandate of price stability instead. The Fed has been working to combat inflation by hiking its interest rate target to a multi-decade high of 5.5% and slowly reducing its bloated balance sheet. This is why you’ve seen car loan and mortgage rates soar to multi-decade highs. These higher rates significantly disrupt the new car and housing markets. But this is the resulting bust after the artificial post-pandemic “boom” as new money moves throughout the economy and manipulated interest rates create malinvestments. We felt the higher inflation rate last year from the Fed’s actions of close to 9%, and now it’s about one-third of that rate, but this remains about 50% higher than its 2% flexible average inflation target. The Fed has stated that it may raise interest rates further. And I believe that it will be forced to raise its target rate to about 6% before this hiking cycle is over. But just raising this rate won’t be enough to curb inflation for long if Congress’ deficit spending remains unchecked. This will force the Fed to monetize it to avoid putting more pressure on Congress to get their irresponsible fiscal house in order. President Biden and Democrats in Congress made this situation worse with the passage of the misnamed Inflation Reduction Act, which is likely to cost about four times the initial $300 billion estimate over a decade. Their wasteful spending, along with Republicans’ excessive spending before them, has led to a fiscal crisis, the most significant national threat. Congress will unlikely make the needed reforms to the primary drivers of the deficit of mandatory spending programs like Social Security and Medicare because of rent-seeking in politics. This will likely result in the Fed not sufficiently cutting its balance sheet to stop inflation. Rather, the Fed will probably choose to increase its balance sheet, putting more inflationary pressure on the economy when that’s the last thing it needs. A vital measure of the economy known as real gross domestic output, the real average of gross domestic product and gross domestic income, has declined in three of the last six quarters. While I don’t want there to be a hard landing, this is the situation that central planners by Congress spending and taxing too much, President Biden regulating too much, and the Fed printing too much have left us. There will be efforts by the government to correct these government failures, but we shouldn’t double down on past mistakes. Let’s learn from these failures and remember the most recent lesson in the 1980s: President Reagan cutting regulations, Congress passing tax cuts (but spending too much), and Fed Chairman Paul Volcker cutting the balance sheet. Initially, the cuts to the Fed’s balance sheet contributed to soaring double-digit interest rates, and the economy suffered a double-dip recession. However, afterward, the economy was able to heal from the prior hindrances of past presidents, congressional members, and the Fed, resulting in a long period of economic prosperity, which is often called the Great Moderation. What we have today is an economy where the government is growing, and markets aren’t as much. This must be reversed. When workers, entrepreneurs, and employers are free to engage in voluntary transactions, competition thrives, innovation flourishes, and resources are allocated efficiently. Moreover, free markets promote consumer choice and personal freedom. When government interventions, such as wasteful spending, excessive regulations, and high taxes, are removed, markets can function more efficiently and respond dynamically to changing economic conditions. Striking the right balance between constitutionally limited government functions and preserving the freedom of markets is crucial for achieving a vibrant and prosperous economy. Rising unemployment, stagnant wages, and the specter of inflation require a multifaceted approach. Raising interest rates hasn’t been enough. The government must focus on responsible fiscal and monetary policies, including reducing government spending, addressing burdensome regulations and taxes, and substantially cutting the Fed’s balance sheet. Americans are still suffering, and there is no time to waste in aggressively assessing these measures that cause economic strain so that people can get back to flourishing instead of merely “making it.” Originally published at Econlib. The Federal Reserve decided at its recent meeting to pause hiking its target interest rate at 5.25% after raising it at 10 consecutive meetings from 0%. But don’t expect the relief to last long as the Fed will likely raise this rate in July and future meetings up to 6% by the end of the year.

The Fed’s current pause has been met with a flurry of hikes in interest rates in other countries, which could mean trouble for Americans. The European Central Bank increased its main rate to 4%; Bank of England hiked its rate to 5%, Turkey raised its rate to 15%, and Argentina hiked its rate to a staggering 97%. Now that higher returns are available in other countries with rising or higher interest rates than in the U.S., the value of the U.S. dollar will fall having a domino effect that would further burden struggling Americans. The Fed will soon have to raise its target interest rate again and likely further than what could have been the case had it not paused. This is because the resulting decline in the value of the dollar will lead to more expensive imports contributing to higher inflation, economic hindrances, and the need for further tightening by the Fed. And financial conditions remain loose as there’s much money sloshing around in the markets, which is why the Fed should be more aggressively cutting its balance sheet instead of focusing so much on its target interest rate. Investors will be drawn to the higher returns available in these high-interest rate countries, which will increase demand for their currencies relative to the U.S. dollar thereby appreciating the foreign currency and depreciating the dollar. This will raise the cost of imports from those countries, leading to more domestic inflation or fewer purchases to satisfy one’s desires. The last thing Americans need is for their purchasing power to be further reduced because we’ve paused our interest rate hikes while so much of the world is doing the opposite. Recent reports reveal that Americans are still struggling because of inflation, which remains hot at about 4% over the last year. Food prices increased in May at home and away from home, and shelter and new vehicle prices are up. While wages are rising slightly, they still aren’t keeping pace with inflation year-over-year for 26 straight months. Times are tough, which is why the Fed needs to cut the one policy tool it can control which is its balance sheet. And by a lot. While the money supply known as M2 and the Fed’s monetary base are declining year-over-year at some of the fastest paces on record because of recent Fed actions, these declines follow the most rapid increases on record, which left their levels extraordinarily high. These extreme increases resulted in persistent inflation and massive distortions across the marketplace. Just as the markets were hurt by the Fed increasing its monetary base, so can the markets improve with fewer distortions by the Fed decreasing its balance sheet. By relying less on government intervention and artificial liquidity, markets can get closer to being free markets. Specifically, the Fed should start cutting its balance sheet by at least 12% year-over-year instead of the current 6% annual rate and removing its injections in mortgage-backed securities and long-term Treasury securities. The result will be a harder economic landing but one that’s necessary given how the government failures over the last couple of years have propped up many areas of the economy with malinvestments that can’t last when cheap credit and loose financial conditions collapse. The resulting recession will be tough, though it was avoidable without these government interventions. But if the government lets markets work, the economy would stabilize more quickly. The long-term result would be that wages keep pace or grow faster than inflation again, cooking at home would be cheaper than eating out, and debts would decrease. Unfortunately, fiscal policy by Congress continues to run amok with massive deficits that must be partially financed by the Fed or risk soaring interest rates, massive net interest payments on the debt, unsustainable budgets, and further soaring inflation and interest rates. This isn’t a pretty scenario but it’s one that officials in D.C. put us in and we must face the difficult choices to get out of it. When the balance sheet is cut and interest rates go up in the U.S., money will flow back into the U.S. helping to appreciate the dollar and reduce the cost of imports. There’s nothing particularly important about trade deficits or surpluses as those are equal to capital account surpluses or deficits, respectively, but the hit to the purchasing power of the dollar for Americans is highly important. Now more than ever, the Fed needs to take drastic measures to improve our economy before it’s choked out by international currencies strengthening. Will it act before it’s too late? Originally published at Daily Caller. Recent reports show that annual inflation rose 4% in May, down from 4.9% in April. In response to this and recent bank failures, the Federal Reserve announced that it’s pausing raising its target interest rate in June after approving 10 consecutive rate hikes, raising its target from nearly zero to a high of 5.25%.

But prices remain elevated and inflation is double the average 2% rate that the Fed prefers, which is making it challenging for Americans to get by. Food prices increased in May at home and away from home faster than 5% year-over-year, and shelter and new vehicle prices are up well above 4%. While wages are rising slightly, they still aren’t keeping pace with inflation year-over-year for 26 straight months. Simply put, times are tough. This is why the Fed needs to use the one policy tool in its box that it directly controls and has the most significant influence on inflation: cutting its balance sheet. Measures of the money supply are declining. The broader money supply known as M2 is down about 5% over the last year, which is the fastest pace since the Great Depression. And the Fed’s monetary base has declined by about 6% over the last year, which is the fastest pace since 2019. But these are after some of the most rapid increases in these measures on record, which leaves their amounts extraordinarily high and manipulative in the marketplace. These extreme increases in measures of the money supply resulted in artificial market distortion as more money was created out of thin air while available goods and services remained stifled by shutdowns, government spending, taxes, and regulations. As this made it more difficult to discern the true value of goods and services, price signals were thwarted. None of these ramifications will be abetted by declining interest rates or pausing rate hikes. Just as the markets were hurt by the Fed increasing its monetary base, so can the markets improve with fewer distortions by the Fed decreasing its balance sheet. By relying less on government intervention and artificial liquidity, markets can get closer to being free markets and clear based on market fundamentals rather than government failures. The Fed should at least double its rate of current cuts to achieve market sanity, meaning at least 12% year-over-year, until it gets to less than 10% of gross domestic product rather than the nearly 50% today. This would be aggressive and result in a harder economic landing but is necessary given the severe market distortions after many markets have been propped up on false strength for years. In the event of a hard landing, spending, employment, and investment would likely be affected as economic activity would be forced to slow down. But if the government lets markets work, the economy would stabilize more quickly. The long-term result would be that wages keep pace or grow faster than inflation again, cooking at home would be cheaper than eating out, and debts would decrease. Unfortunately, since overspending is a bi-partisan problem, political pushback would likely ensue if the Fed goes this route as it will mean a higher cost of funding the massive national debt. Although cutting the balance sheet is the solution, a cultural shift among politicians that favors less spending must preclude it because the Fed is implicitly and explicitly helping the federal government from blowing up the budget more with even higher net interest payments. Ultimately, the path toward a stronger and more prosperous economy lies in the Fed's willingness to take bold actions and the political will to embrace responsible spending and balance sheet practices. A brighter economic future can be achieved by prioritizing market stability over short-term political considerations. Originally published at The Center Square. This Week's Economy Ep. 14 | Inflation is Americans’ Top Concern, State Jobs Report, & Minimum Wage6/23/2023 Thank you for reading the Let People Prosper newsletter, which today includes the 12th episode of "This Week's Economy,” where I briefly share insights every Friday on key economic and policy news across the country. Today, I cover: 1) National: New Pew Research poll reveals that inflation is the top concern for Americans on both sides of the political aisle, Fed needs to do more, and financial markets remain loose; 2) States: New state-level jobs report and which states are leading and breakdown of the largest spending increase in Texas history and why it's not good for keeping the Texas Model strong; and 3) Other: The importance of educating young audiences on capitalism and socialism and my experience teaching with a "minimum wage" game to a group of high school students. You can watch this episode and others along with my Let People Prosper Show on YouTube or listen to it on Apple Podcast, Spotify, Google Podcast, or Anchor. Please share, subscribe, like, and leave a 5-star rating!

For show notes, thoughtful insights, media interviews, speeches, blog posts, research, and more, check out my website (https://www.vanceginn.com/) and please subscribe to my newsletter (www.vanceginn.substack.com), share this post, and leave a comment. TRUTH On Inflation, Housing Market, Interest Rates, & Incentives w. Dr. Chuck Beauchamp | Ep. 445/16/2023 In today's new episode of the "Let People Prosper" podcast, I'm thankful to be joined by Dr. Chuck Beauchamp for a thought-provoking discussion on new inflation numbers and the current economy. We discuss: 1) The newest inflation numbers and how the rate is impacting various markets including food, housing, and energy; 2) Interest rates' impact on the housing market and the crisis of affordability; and 3) Why the U.S. dollar's status could continue to wane and more. You can watch this interview on YouTube or listen to it on Apple Podcast, Spotify, Google Podcast, or Anchor (please share, subscribe, like, and leave a 5-star rating). Chuck’s bio:

Find show notes, thoughtful economic insights, media interviews, speeches, blog posts, research, and more here at my website (https://www.vanceginn.com/) or Substack newsletter (https://vanceginn.substack.com). Please subscribe to the newsletter, share it with your friends and family, and leave me a comment. The U.S. dollar will likely soon lose its status as the global reserve currency. The dollar’s global reserve dominance has declined in recent years. As a result, international trade partners are hedging new connections. This will restructure the global economic order and create challenges ahead, especially for middle-class Americans.

Americans should know what’s happening and how they can prepare for this possibility. But first, what does it mean to be the world’s global reserve currency, and why does it matter? The U.S. Dollar is the dominant global reserve currency. It’s widely accepted and is the preferred medium of exchange for international transactions. The dollar has enjoyed this status for the past 80 years due to its strong reputation acquired across a long history of America’s rising military prowess, fulfilling its financial obligations, and maintaining a strong economy. These institutional foundations of the dollar created high demand among foreign entities. One of the most important transactions utilizing the dollar is the purchase of oil. Oil is currently priced in dollars globally and other dollar-denominated assets. Losing or weakening the dollar’s position and value results in higher oil prices. The dollar’s elevated demand has helped keep its value high relative to other currencies. This prompted many countries to tie their currency directly to our dollar. The U.S. benefited by leveraging foreign demand for dollars into loans to the U.S. federal government. Foreign investors lend the U.S. high volumes of money because of the debt’s dollar denomination. The higher demand for U.S. Treasury securities pushes down domestic interest rates. This influences lower rates on mortgages and business loans, which help provide increased investment and economic growth. Losing or weakening the dollar’s reserve position will result in increased interest rates, decreased investment, and weak to negative economic growth. The dollar’s reserve status has also meant an increased volume of international trade. Ultimately, international trade helps keep interest rates and inflation moderately low. Losing or weakening the dollar’s reserve position will result in increased inflation. Trouble for the dollar is on the horizon. The once-givens about the dollar have come into question recently due prominently to excessive deficit spending. Foreign investors are reducing their demand for dollars as they diversify their portfolios. This combination contributed to the ballooning of the debt, depreciated the dollar, led to higher inflation and falling year-over-year real average weekly earnings for 25 straight months, and drove up interest rates, thereby slowing economic activity. Of course, this will have tradeoffs and many of them won’t be good. As mentioned, the major tradeoffs will be higher inflation and interest rates. The latter will trigger a move by the Federal Reserve to attempt to lower interest rates. But if its target rate is held below what markets dictate, the Fed will monetize the debt, increase the money supply, and drive inflation higher. The long-term result will be even higher interest rates to tame inflation. Unfortunately, the consequences of higher interest rates and inflation would be severe. People should expect higher mortgage rates than the already rising average rate of 6.4%. This is the highest in 15 years. Ultimately, higher interest rates would result in a steeper contraction in the housing market, exacerbate economic weakness, increase job losses, and worsen poverty. But maybe more importantly, it would likely crush middle-class Americans and the lifestyle that they’ve been accustomed to having for decades. The higher cost of shelter, food, gasoline, and energy as the dollar loses its reserve currency status would wreck havoc on their budgets and force major decisions about what’s best for their families. This could mean having to put off saving for college, going on vacations, and living in much smaller homes. All because our government couldn’t spend our money wisely. Therefore, the government should take serious steps to restore confidence in the dollar before a bad situation for Americans becomes worse or irreconcilable. To start, the federal government should reduce deficit spending. The long-term goal should be a balanced budget and an eventual start to paying down the debt. This will be pro-growth as the government stops redistributing taxpayer money from productive to unproductive activities. It will also strengthen the fiscal and economic situation of the U.S. The result will be an improvement in foreigners’ outlook on the dollar that would help preserve the dollar’s status. Dollar-focused policies should be tied to reducing the money in circulation. This should occur as the Federal Reserve reduces its balance sheet. Doing so tames inflationary pressures and could even result in some disinflation. This would allow the hard-earned dollars of Americans to go further than they do today. These policy improvements should be put into law with fiscal and monetary policy rules. The rules should remove the discretion of big-government spenders and printers. This would enable people’s livelihoods to get back on track and improve for generations. The potential loss of the dollar’s reserve currency status could have significant economic consequences, and there are even more than highlighted here. There is, however, reason for optimism: The U.S. economy is resilient and adapts well to challenges. But will those in D.C. allow for that to happen in the dynamic marketplace? Time will tell. But let’s hope so before it’s too late for middle-class Americans and everyone else to have the opportunity to fulfill their hopes and dreams. Originally published at The Daily Caller with Chuck Beauchamp, Ph.D. On today's episode of the "Let People Prosper" show, I'm thankful to be joined by Dr. Larry White, Professor of Theory and History of Banking and Money at George Mason University and author of the new book "Better Money: Gold, Fiat, or Bitcoin?" We discuss:

You can watch this interview on YouTube or listen to it on Apple Podcast, Spotify, Google Podcast, or Anchor (please share, subscribe, like, and leave a 5-star rating). Dr. White’s bio:

For show notes, thoughtful economic insights, media interviews, speeches, blog posts, research, and more, check out my personal website and subscribe to my Substack newsletter where you can get every episode in your inbox. The U.S. dollar is the cornerstone of the global financial system but is facing a crisis of confidence from decades of reckless fiscal and monetary policies. If this continues, the dollar could soon lose its global reserve currency status. Global competitors such as China and Russia are taking advantage of these reckless policies, further threatening trust in the dollar.

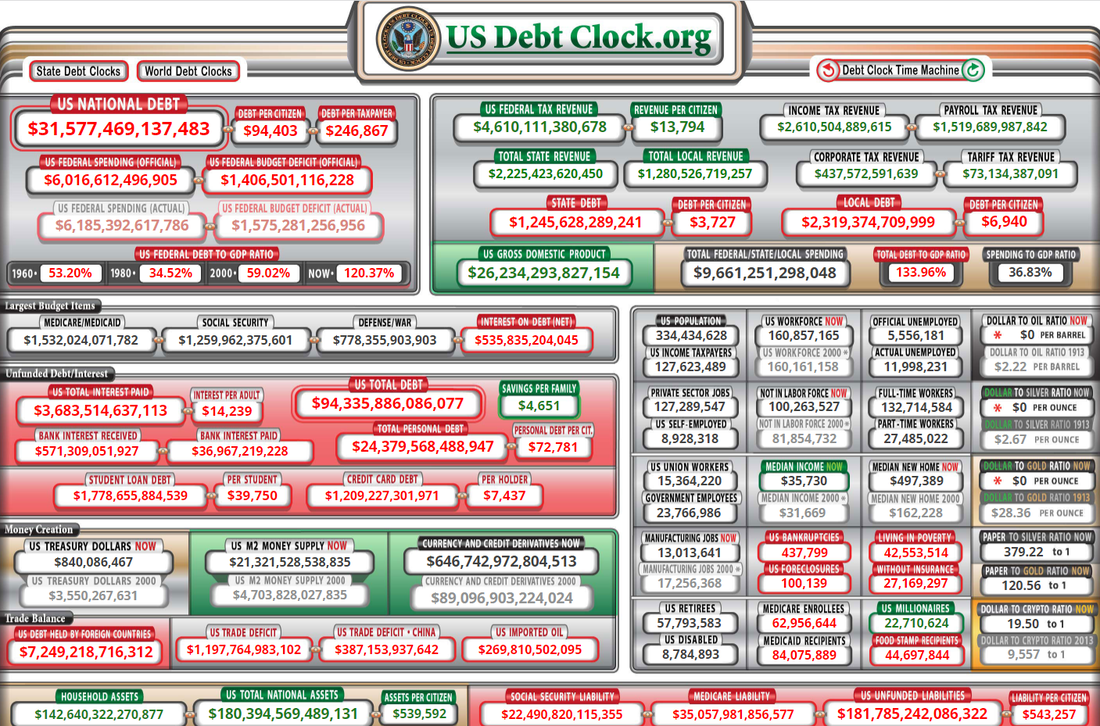

Confidence in a currency is only as strong as that of the institutions issuing the currency. In the dollar’s case, those institutions are the federal government and the Federal Reserve. Both have been irresponsible in their respective fiscal or monetary policies, and the ramifications of their mischief for the dollar would be a weaker economy and higher inflation domestically and a reshuffling of economic power globally. Since early 2020, Congress has added more than $7 trillion to the national debt from massive deficit spending. Congress financed this by issuing U.S. Treasury securities, crowding out investments like private sector equities and bonds. Additionally, net interest payment on U.S. debt is about 8% of the federal budget and increasing rapidly. Interest expenses are expected to exceed spending on national defense or safety nets soon if Congress fails to rein in excess spending. While the House Republicans’ bill to raise the debt ceiling and cut spending is promising, it’s unlikely to go anywhere with Democrats in charge of the Senate and the White House. Since the early 2000s, the Federal Reserve has held its target federal funds rate too low for too long. And in 2008, it started purchasing longer-term Treasury securities and other assets, known as quantitative easing. The Fed operates under a dual mandate of encouraging stable prices and pursuing full employment. It violated the former part of the mandate through asset purchases that fueled inflation. It now violates the latter part of the mandate as it crushes employment with quantitative tightening and the resulting higher interest rates, hence what’s known as the “boom-and-bust cycle.” These violations, combined with its early incoherent messaging on inflation, erode confidence in the Fed’s monetary policy prowess. And this is far from a domestic concern, as global trade partners see the writing on the wall and are acting accordingly. And if confidence in the dollar continues to wane, so will the Fed’s ability to conduct monetary policy effectively by not being able to substantially influence market interest rates. Recently, the Saudi Arabian government approved partial membership with China’s Shanghai Cooperation Organization. This is part of China’s strategy to expand its influence beyond the West. China conducted its “first major lNG sale in renminbi instead of dollars” and made Brazil its main trading partner instead of the U.S. Other countries are also beginning to move away from the dollar for international transactions. Countries across the globe know the U.S. is in economic trouble and are changing the way they do business. We should react accordingly, beginning with ending these government policy failures weakening the U.S. economy and the dollar. First, we should address excessive fiscal and monetary policy discretion by Congress and the Federal Reserve, respectively. This can be achieved by rules-based policies, such as a strict government spending limit for Congress and the Taylor rule for the Fed. Doing so would reduce the costly mountain of debt created by Congress and the monetary mischief by the Fed, helping to provide confidence in the economy and dollar. Second, the U.S. should eventually move off the fiat currency system eventually. The dollar should be backed by real assets like gold and silver. Reimplementing the gold standard or something with underlying value from productive use of capital and labor, making it more attractive to domestic and international investors. Finally, the U.S. must take international trade seriously. It should adopt a foreign policy of peace and goodwill through free-trade agreements with countries that benefit all parties. Tariffs and other protectionist measures do not provide that path. They lead to trade wars and tension between countries and hurt people’s livelihoods across the globe. Encouragement of global trade would support a stronger dollar. Failing to take these steps will continue the slide of confidence and value of the dollar globally. It also jeopardizes the economic future of our country. This will result in more U.S. global partners exiting agreements and reducing investment in America. The consequences will be a weak economy and dollar that will hurt Americans. Originally posted at Daily Caller and co-authored with Chuck Beauchamp. In co-dependent relationships, there’s often an enabler compounding the destructive behavior. In the case of the Silicon Valley Bank collapse and a possible crisis for the banking industry, the Federal Reserve and its fast-and-loose monetary policy is that toxic enabler. If only couples counseling could fix the muddled relationship between the Fed and the banking industry.

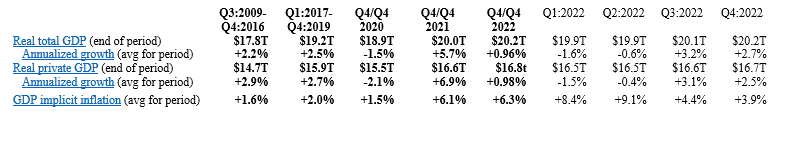

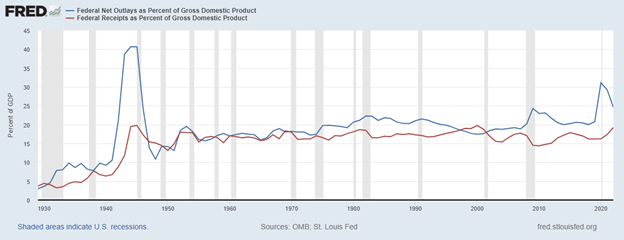

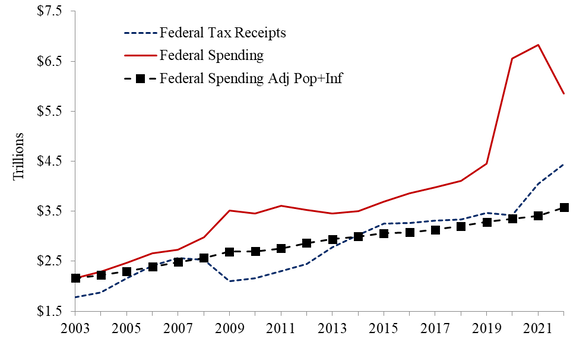

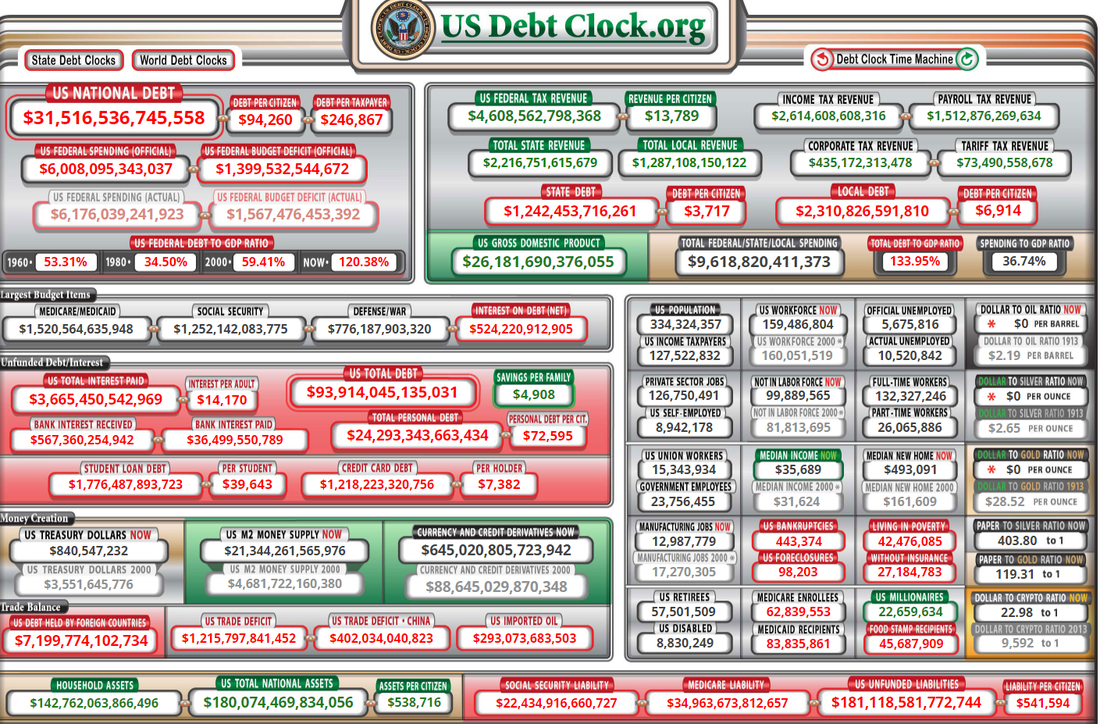

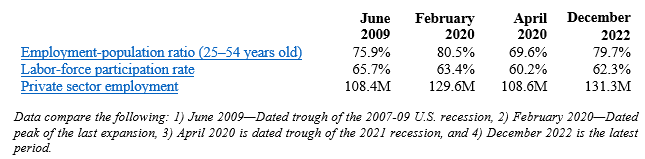

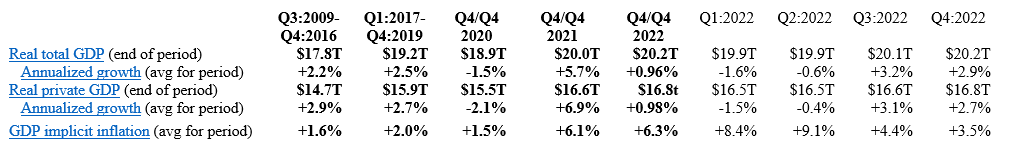

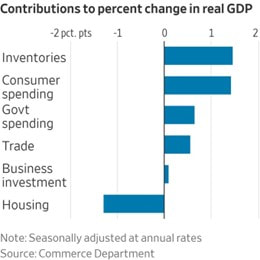

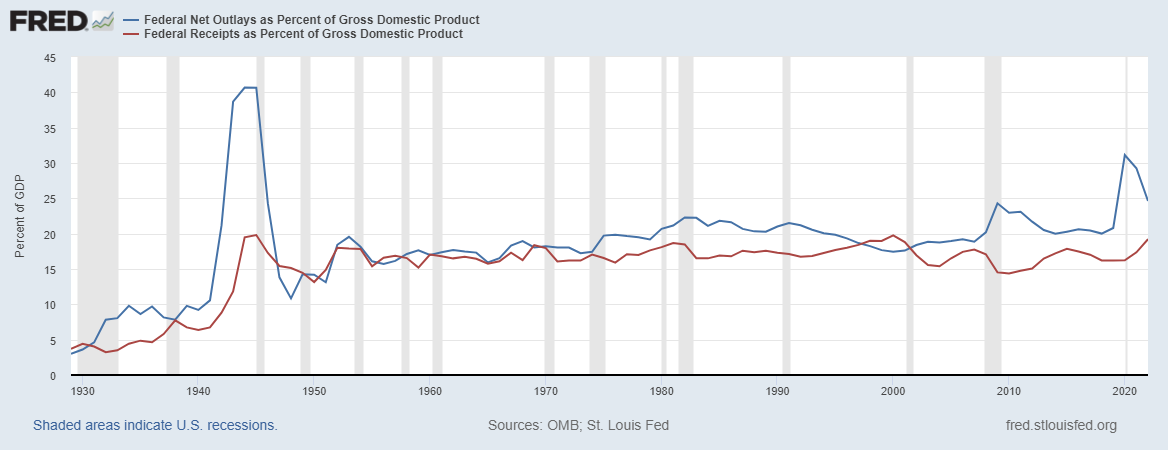

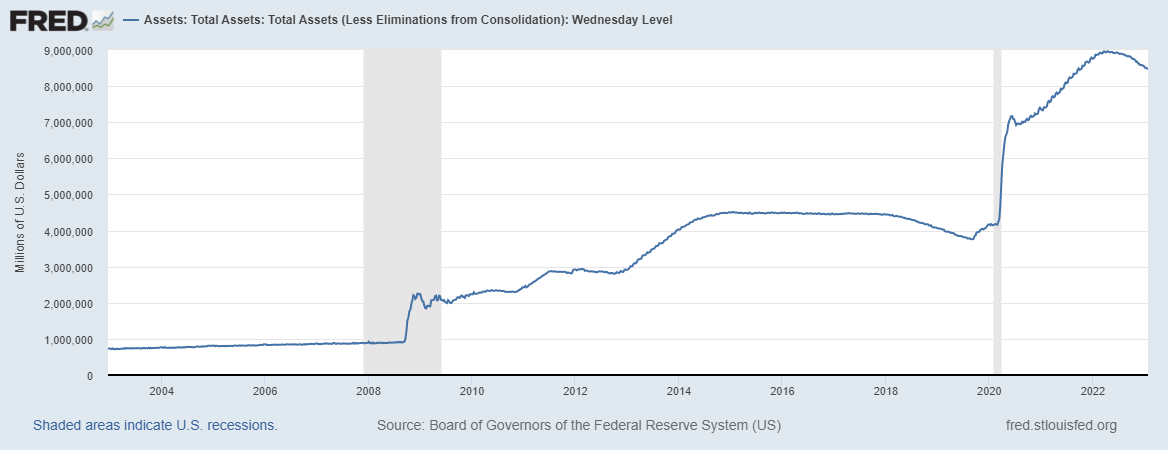

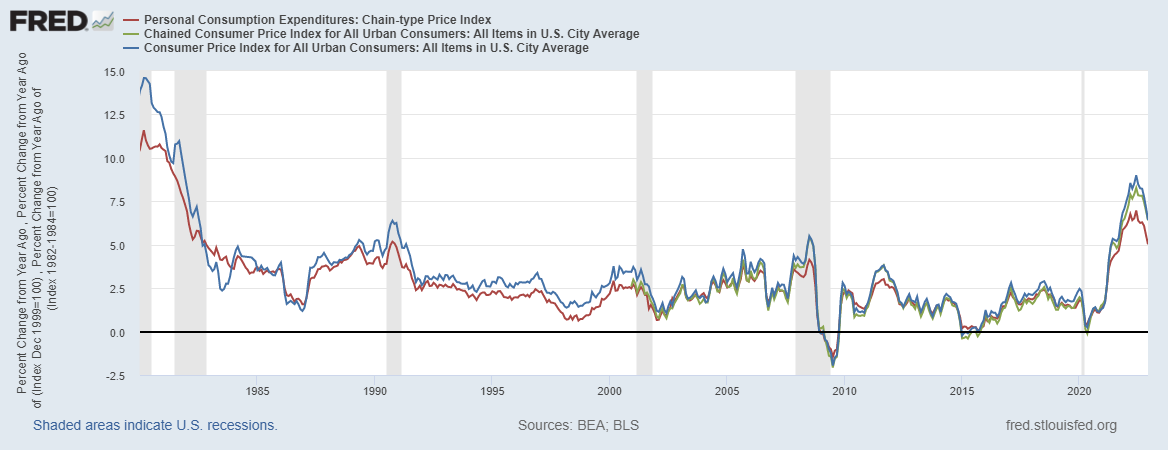

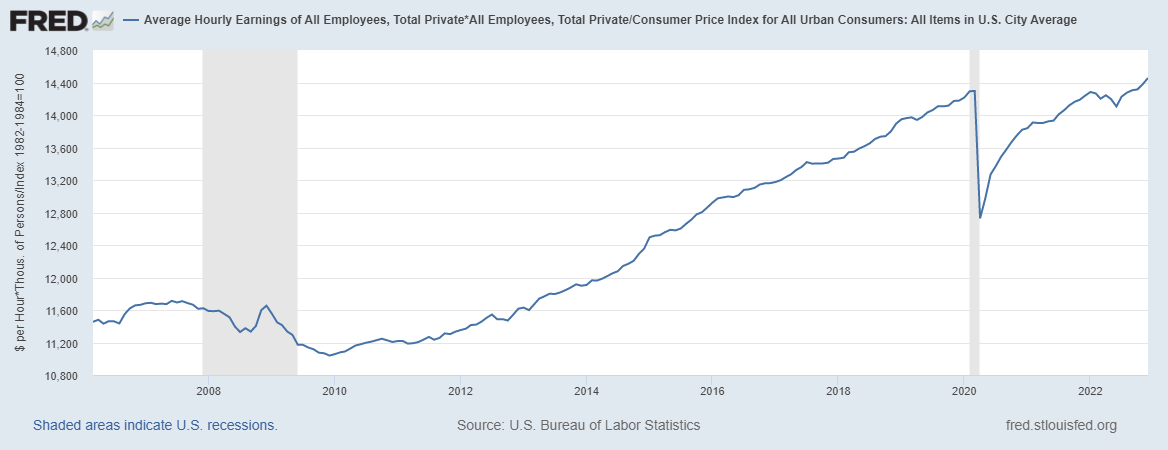

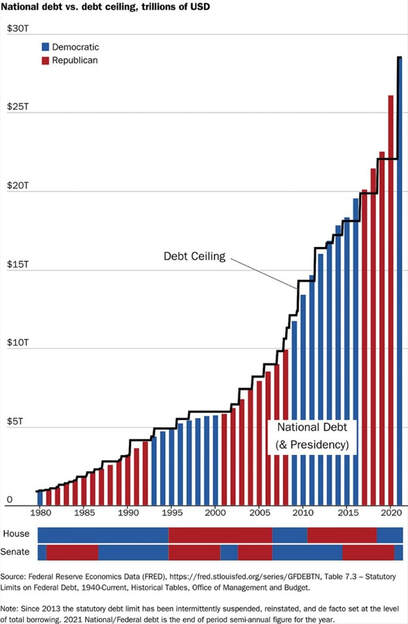

Over the past three years, the Fed has monetized much of Congress’s excessive deficit spending, thereby bringing inflation to a 40-year high and distorting the banking industry and economy. To take advantage of that extra liquidity, SVB (and many other banks) invested in riskier assets: interest-rate-sensitive bonds. Banks were unprepared for the Fed’s sudden pivot last year when it began increasing interest rates in an effort to control elevated inflation. To be sure, they ignored many warning signs, such as a bloated Fed balance sheet and supply chain disruptions. And when the Fed raised its target federal funds rate from near 0% to today’s range of 4.75% to 5%, bonds began losing significant value. In SVB’s case, the bank had to realize huge losses when it made its mark-to-market calculations for its balance sheet, as it shifted investments from hold-to-maturity to available-for-sale status, hoping to satisfy its depositors by selling those assets. The losses proved too substantial, rendering the bank insolvent. The actions of the Fed certainly incentivized the kind of risk-taking that led to SVB’s insolvency and failure, but the bank was far from an innocent victim as it abandoned basic risk management. It loaded its balance sheet with risky investments while prioritizing social agendas over profits, investing in ESG initiatives that performed poorly. At the time of its failure, SVB looked more like a hedge fund than a commercial bank. But instead of letting SVB and its depositors face the consequences of the bank’s mismanagement, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, Federal Reserve, Department of Treasury, and White House launched coordinated rescue actions, determining that all depositors of the failed bank would be saved. The FDIC’s traditional policy of insuring accounts up to $250,000 was seemingly obliterated by this decision, establishing an entirely new regime. The Fed and FDIC justified the SVB rescue by claiming that the bank represented a “systemic risk” though it was only a mid-level-sized bank. This further muddied the waters as to how the Fed and FDIC determine which institutions are “too big to fail.” Further compounding the issue was Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen’s testimony to the Senate Finance Committee guaranteeing all deposits of “Too Big to Fail” banks. The fallout from this new regime, which focuses only on the deposits of the largest banks, creates an incentive for depositors with more than $250,000 to shift their deposits to the largest banks that will accept them. This will put pressure on mid-level and smaller banks as they must now compete for larger deposits that will be uninsured at their banks. The result of this challenge will likely be more consolidation across the banking sector, thus making the big banks that much larger. In a sane society, troubled banks such as SVB would be allowed to fail, and the depositors would lose their deposits above the $250,000 insured amount. But financial socialism is growing. Profits are privatized, losses are socialized, and everyone in government is tripping over each other to bail someone out. The current rescue actions and the promise of more are not a part of the free market capitalism that has supported wealth and prosperity throughout America’s history. These actions send a loud and clear signal to all banks: go ahead and take the risk! We’ll finance your failure with a more accommodative monetary policy. It should come as no surprise when more banks begin backsliding due to this messaging. As things stand, no sector, including the banking industry, is incentivized via market discipline to reduce risky behaviors thanks to the government’s outsize role. The ones who suffer most from this are consumers seeking services, who will inevitably be left with more mediocre options as government handouts cover competition. To avoid this and strengthen the economy, Washington needs to end bailouts. The Fed needs to keep raising its target federal funds rate and more aggressively reduce its bloated balance sheet, which it increased by $300 billion recently, to rein in inflation and let markets work. Likewise, Congress should cut spending to stop issuing so many Treasury securities that fund the more than $31 trillion national debt. This system where the Fed micromanages the free market instead of allowing the free market to work out problems on its own will continue to impoverish the economy. Indeed, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell’s suggestion last week that target rate hiking is nearing an end means Americans can expect more inflation and more economic distortions for a longer period of time. The recent events provide further evidence that it is past time to reevaluate the structure, governance, and operating rules of the Fed. Indeed, Washington’s response to the SVB failure proves the entire financial arm of the government ought to be thoroughly reformed so that market discipline can be returned to the banking sector. If significant change doesn’t happen, the troubled co-dependent relationship between the banking sector, the Fed, and Washington’s bureaucracy will never heal. For Americans, that means waiting on the next Fed-fueled boom and bust cycle. Originally published at the Washington Examiner. Key Point: The U.S. economy in 2022 had the slowest Q4-over-Q4 growth during a recovery since at least 2009 and average weekly earnings are now down for 22 straight months as inflation keeps roaring. But there’s hope if we just give free-market capitalism a chance to let people prosper. Overview: Although President Biden recently tried to claim that the state of the union is strong, facts tell a different story. The government failures that drove the “shutdown recession,” high inflation, and weak economic growth over the last three years continue to plague Americans. This includes excessive federal spending leading to massive deficit spending adding up to $7 trillion since January 2020 to reach nearly $31.5 trillion in national debt—about $250,000 owed per taxpayer. This has created a fight between the Biden administration and House Republicans over the debt ceiling, as raising it must come with spending restraint to avoid some of the fiscal insanity that will lead to insolvency if nothing is changed. And more inflation could be on the horizon if the Federal Reserve chooses to monetize more more of the new debt, which past excess has already contributed to 40-year-high inflation rates. These government failures with little relief from pro-growth policies in sight mean that things will get worse before they get better. Labor Market: The Bureau of Labor Statistic recently released its U.S. jobs report for January 2022. This report came with substantial revisions to seasonal adjustments and population estimates which could bias the data for a while given that the revised estimates include the much of the last three years of data that are highly volatile. And recall the recent report by the Philadelphia Fed finds that if you add up the jobs added in states in Q2:2022 there were just 10,500 net new jobs rather than more than 1 million reported. The establishment survey shows there were +517,000 (+3.3%) net nonfarm jobs added in January to 155.1 million employees, with +443,000 (+3.6%) added in the private sector and +74,000 (+1.4%) jobs added in the government sector. Most of the private sector jobs were added in the sectors of leisure and hospitality (+128,000), private education and health services (+105,000), and professional and business services (+82,000), which these three sectors led over the last 12 months as well; information (-5,000) and utilities (-700) were the only net job declines over the last month and no sector had net job losses over the last year. Average hourly earnings for all employees was up by 10 cents last month to $33.03, or up by +4.4% over the last year. And average weekly earnings in the private sector increased by $13.35 last month to $1,146, or up by +4.7% over the 12 months. The household survey had another large increase of +894,000 jobs added to 160.1 million employed There have been declines in net jobs in four of the last 10 months for a total increase of +1.8 million since March 2022, which is about half of the +3.6 million of the net jobs added per the establishment survey. The official U3 unemployment rate declined slightly to 3.4% which is the lowest since 1969. But challenges remains as inflation-adjusted average weekly earnings were down -1.5% over the last year for the 22nd straight month, weighing on Americans budgets to make ends meet. And since February 2020 before the shutdown recession, the prime age (25-54 years old) employment-population ratio was 0.3-percentage point lower, prime-age labor force participation rate was 0.3-percentage point lower, and the total labor-force participation rate was 0.9-percentage-point lower with millions of people out of the labor force thereby holding the U3 unemployment rate much lower than otherwise. Economic Growth: The U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis’ recently released the 2nd estimate for economic output for Q4:2022. The following table provides data over time for real total gross domestic product (GDP), measured in chained 2012 dollars, and real private GDP, which excludes government consumption expenditures and gross investment. And most of the estimates for Q4:2022 and growth in 2022 were revised lower, providing more evidence that 2022 was a very weak year if not a recession. The shutdown recession in 2020 had GDP contract at historic annualized rates because of individual responses and government-imposed shutdowns related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Economic activity has had booms and busts thereafter because of inappropriately imposed government COVID-related restrictions in response to the pandemic and poor fiscal policies that severely hurt people’s ability to exchange and work. Since 2021, the growth in nominal total GDP, measured in current dollars, was dominated by inflation, which distorts economic activity. The GDP implicit price deflator was +6.1% for Q4-over-Q4 2021, representing half of the +12.2% increase in nominal total GDP. This inflation measure was +9.1% in Q2:2022—the highest since Q1:1981—for a +8.5% increase in nominal total GDP that quarter. This made two consecutive declines in real total (and private) GDP, providing a criterion to date recessions every time since at least 1950. In Q3:2022, nominal total GDP was +7.6% and GDP inflation was +4.4% for the +3.2% increase in real total GDP. But if inflation had been as high as it was in the prior two quarters or had the contribution of net exports of goods and services (driven by natural gas exports to Europe) not been 2.9%, real total GDP would have either declined or been essentially flat for a third straight quarter. In Q4:2022, there was a similar story of weakness as nominal total GDP was +6.6% and GDP inflation was +3.9% for the +2.7% increase in real total GDP. But if you consider the +2.7% real total GDP growth was driven by contributions of volatile inventories (+1.5pp), government spending (+0.6pp), and next exports (+0.5pp) which total +2.6pp, the actual growth is quite tepid like it was in Q3:2022. For all of 2022, real total GDP growth is reported +2.1% year-over-year but measured by Q4-over-Q4 the growth rate was only +0.9%, which was the slowest Q4-over-Q4 growth for a year since 2009 (last part of Great Recession). The Atlanta Fed’s early GDPNow projection on February 24, 2023 for real total GDP growth in Q1:2023 was +2.7% based on the latest data available. The table above also shows the last expansion from June 2009 to February 2020. A reason for slower real private GDP growth in the latter period is due to higher deficit-spending, contributing to crowding-out of the productive private sector. Congress’ excessive spending thereafter led to a massive increase in the national debt by more than +$7 trillion that would have led to higher market interest rates. This is yet another example of how there is always an excessive government spending problem as noted in the following figure with federal spending and tax receipts as a share of GDP no matter if there are higher or lower tax rates. But the Fed monetized much of the new debt to keep rates artificially lower thereby creating higher inflation as there has been too much money chasing too few goods and services as production has been overregulated and overtaxed and workers have been given too many handouts. The Fed’s balance sheet exploded from about $4 trillion, when it was already bloated after the Great Recession, to nearly $9 trillion and is down only about 6.5% since the record high in April 2022. The Fed will need to cut its balance sheet (see first figure below with total assets over time) more aggressively if it is to stop manipulating so many markets (see second figure with types of assets on its balance sheet) and persistently tame inflation, which there’s likely a need for deflation for a while given the rampant inflation over the last two years. The resulting inflation measured by the consumer price index (CPI) has cooled some from the peak of +9.1% in June 2022 but remains hot at +6.4% in January 2023 over the last year, which remains at a 40-year high (highest since July 1982) along with other key measures of inflation (see figure below). After adjusting total earnings in the private sector for CPI inflation, real total earnings are up by only +2.2% since February 2020 as the shutdown recession took a huge hit on total earnings and then higher inflation hindered increased purchasing power. Just as inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon, deficits and taxes are always and everywhere a spending problem. The figure below (h/t David Boaz at Cato Institute) shows how this problem is from both Republicans and Democrats. As the federal debt far exceeds U.S. GDP, and President Biden proposed an irresponsible FY23 budget and Congress never passed one until the ridiculous $1.7 trillion omnibus in December, America needs a fiscal rule like the Responsible American Budget (RAB) with a maximum spending limit based on population growth plus inflation. If Congress had followed this approach from 2003 to 2022, the figure below shows tax receipts, spending, and spending adjusted for only population growth plus chained-CPI inflation. Instead of an (updated) $19.0 trillion national debt increase, there could have been only a $500 billion debt increase for a $18.5 trillion swing in a positive direction that would have substantially reduced the cost of this debt to Americans. Of course, part of this includes the Great Recession and the Shutdown Recession, so these periods would have likely been good reason to exceed the limit, but regardless we would be in a much better fiscal and economic situation with this fiscal rule. The Republican Study Committee recently noted the strength of this type of fiscal rule in its FY 2023 “Blueprint to Save America.” And to top this off, the Federal Reserve should follow a monetary rule so that the costly discretion stops creating booms and busts. Bottom Line: While there appears to be a strengthening labor market in January, let’s see if this continues as my guess is that these were biased from the data adjustments, and we will see a weaker labor market in the months to come. My expectation is that stagflation will continue along with the a deeper recession this year given the “zombie economy” with “zombie labor” of many workers sitting on the sidelines and others are “quiet quitting” along with the failures of many “zombie firms” that live on debt. Ultimately, Americans are struggling from bad policies out of D.C.. Instead of passing massive spending bills, the path forward should include pro-growth policies. These policies ought to be similar to those that supported historic prosperity from 2017 to 2019 that get government out of the way rather than the progressive policies of more spending, regulating, and taxing. The time is now for limited government with sound fiscal and monetary policy that provides more opportunities for people to work and have more paths out of poverty.

Recommendations:

Key Point: Americans are suffering under big-government policies as average weekly earnings adjusted for inflation are down for 21 straight months. It's time for pro-growth policies to unleash economic potential to let people prosper. Overview: The irresponsible “shutdown recession” and subsequent government failures have led to a longer, deeper recession with high inflation that are having persistent consequences for many Americans’ livelihoods. This includes excessive federal spending redistributing scarce private sector resources with deficit spending of more than $7 trillion since January 2020 to reach the new high of $31.4 trillion in national debt—about $95,000 owed per American or $250,000 owed per taxpayer. This new debt has hit its limit and needs to be addressed with spending restraint as the Federal Reserve monetized most of the new debt, leading to a 40-year-high inflation rates. The failed policies of the Biden administration, Congress, and the Fed must be replaced with a liberty-preserving, free-market, pro-growth approach by the new majority by House Republicans so there are more opportunities to let people prosper. Labor Market: The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics recently released the U.S. jobs report for December 2022. The BLS’s establishment report shows there were 223,000 net nonfarm jobs added last month, with 220,000 added in the private sector. Interestingly, while there have appeared to be a relatively robust number of jobs created, a recent report by the Philadelphia Fed find that if you add up the jobs added in states in Q2:2022 there were just 10,500 net new jobs rather than more than 1 million initially estimated. This further indicates that the recession started in (likely) March 2022 (more on this below). That expected revision to the establishment report supports the weak data in the BLS’s household survey, which employment increased by 717,000 jobs last month but had declined in four of the last nine months for a total increase of 916,000 jobs since March 2022. This number of net jobs added since then is much lower than the report 2.9 million payroll jobs in the establishment. The official U3 unemployment rate declined slightly to 3.5%, but challenges remain, including: 3.1% decline in average weekly earnings (inflation-adjusted) over the last year, 0.4-percentage point lower prime-age (25–54 years old) employment-population ratio than in February 2020, 0.6-percentage point below prime-age labor force participation rate, and 1.0-percentage-point lower total labor-force participation rate with millions of people out of the labor force. These data support my warnings for months of stagflation, recession, and a “zombie economy.” This includes “zombie labor” as many workers are sitting on the sidelines and others are “quiet quitting” while there’s a declining number of unfilled jobs than unemployed people to 4.5 million And that demand for labor is likely inflated from many “zombie firms,” which run on debt and could make up at least 20% of the stock market and will likely lay off workers with rising debt costs. Economic Growth: The U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis’ released economic output data for Q4:2022. The following provides data for real total gross domestic product (GDP), measured in chained 2012 dollars, and real private GDP, which excludes government consumption expenditures and gross investment. The shutdown recession in 2020 had GDP contract at historic annualized rates because of individual responses and government-imposed shutdowns related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Economic activity has had booms and busts thereafter because of inappropriately imposed government COVID-related restrictions in response to the pandemic and poor fiscal policies that severely hurt people’s ability to exchange and work. Since 2021, the growth in nominal total GDP, measured in current dollars, was dominated by inflation, which distorts economic activity. The GDP implicit price deflator was +6.1% for Q4-over-Q4 2021, representing half of the +12.2% increase in nominal total GDP. This inflation measure was +9.1% in Q2:2022—the highest since Q1:1981—for a +8.5% increase in nominal total GDP that quarter. This made two consecutive declines in real total (and private) GDP, providing a criterion to date recessions every time since at least 1950. In Q3:2022, nominal total GDP was +7.6% and GDP inflation was +4.4% for the +3.2% increase in real total GDP. But if inflation had been as high as it was in the prior two quarters or had the contribution of net exports of goods and services (driven by natural gas exports to Europe) not been 2.9%, real total GDP would have either declined or been essentially flat for a third straight quarter. In Q4:2022, there was a similar story of weaknesses as nominal total GDP was +6.4% and GDP inflation was +3.5% for the +2.9% increase in real total GDP. But if you consider the +2.9% real total GDP growth was driven by contributions of volatile inventories (+1.5pp), government spending (+0.6pp), and next exports (+0.6pp) which total +2.7pp, the actual growth is quite tepid. For all of 2022, real total GDP growth is reported +2.1% year-over-year but measured by Q4-over-Q4 the growth rate was only +0.96%, which was the slowest Q4-over-Q4 growth for a year since 2009 (last part of Great Recession). The Atlanta Fed’s early GDPNow projection on January 27, 2023 for real total GDP growth in Q1:2023 was +0.7% based on the latest data available. The table above also shows the last expansion from June 2009 to February 2020. The earlier part of the expansion had slower real total GDP growth but had faster real private GDP growth. A reason for this difference is higher deficit-spending in the latter period, contributing to crowding-out of the productive private sector. Congress’ excessive spending thereafter led to a massive increase in the national debt that would have led to higher market interest rates. This is yet another example of how there is always an excessive government spending problem as noted in the following figure with federal spending and tax receipts as a share of GDP. But the Fed monetized much of it to keep rates artificially lower thereby creating higher inflation as there has been too much money chasing too few goods and services as production has been overregulated and overtaxed and workers have been given too many handouts. The Fed’s balance sheet exploded from about $4 trillion, when it was already bloated after the Great Recession, to nearly $9 trillion and is down only about 6% since the record high in April 2022. The Fed will need to cut its balance sheet (see first figure below with total assets over time) more aggressively if it is to stop manipulating so many markets (see second figure with types of assets on its balance sheet) and persistently tame inflation. The resulting inflation measured by the consumer price index (CPI) has cooled some from the peak of 9.1% in June 2022 but remains hot at 6.5% in December 2022 over the last year, which remains at a 40-year high (highest since June 1982) along with other key measures of inflation (see figure below). After adjusting total earnings in the private sector for CPI inflation, real total earnings are up by only 1.1% since February 2020 as the shutdown recession took a huge hit on total earnings and then higher inflation hindered increased purchasing power. Just as inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon, high deficits and taxes are always and everywhere a spending problem. The figure below (h/t David Boaz at Cato Institute) shows how this problem is from both Republicans and Democrats. As the federal debt far exceeds U.S. GDP, and President Biden proposed an irresponsible FY23 budget and Congress never passed one until the ridiculous $1.7 trillion omnibus in December, America needs a fiscal rule like the Responsible American Budget (RAB) with a maximum spending limit based on population growth plus inflation. If Congress had followed this approach from 2002 to 2021, the (updated) $17.7 trillion national debt increase would instead have been a $1.1 trillion decrease (i.e., surplus) for a $18.8 trillion swing to the positive that would have reduced the cost to Americans. The Republican Study Committee recently noted the strength of this type of fiscal rule in its FY 2023 “Blueprint to Save America.” And the Federal Reserve should follow a monetary rule.

Bottom Line: Americans are struggling from bad policies out of D.C., which have resulted in a recession with high inflation. Instead of passing massive spending bills, like passage of the “Inflation Reduction Act” that will result in higher taxes, more inflation, and deeper recession, the path forward should include pro-growth policies. These policies ought to be similar to those that supported historic prosperity from 2017 to 2019 that get government out of the way rather than the progressive policies of more spending, regulating, and taxing. The time is now for limited government with sound fiscal and monetary policy that provides more opportunities for people to work and have more paths out of poverty. Recommendations:

Vance Ginn sits down with Newsmakers to discuss the battle against inflation and the rising interest rates the Fed is imposing yet again. He touches on major economic benchmarks and explains what the numbers are really showing.

Watch here: https://www.youmaker.com/video/482a32b6-d37b-47bb-b6db-0ed3d975f04f The latest inflation report reveals that inflation is slowing, but it remains at a 40-year high.