|

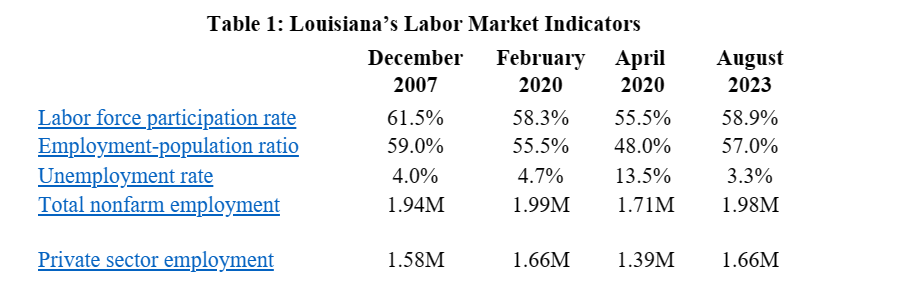

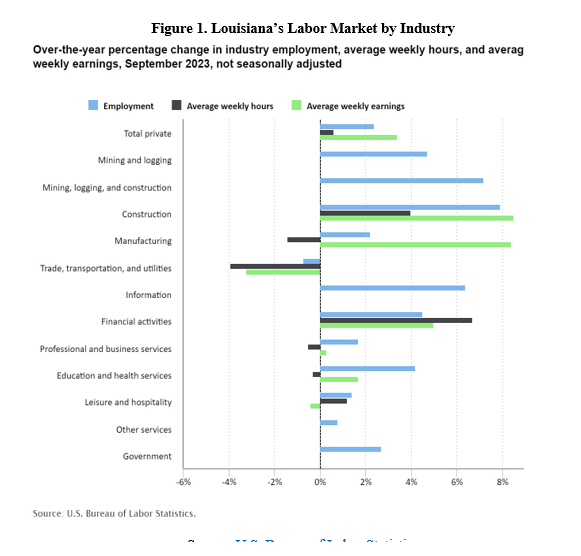

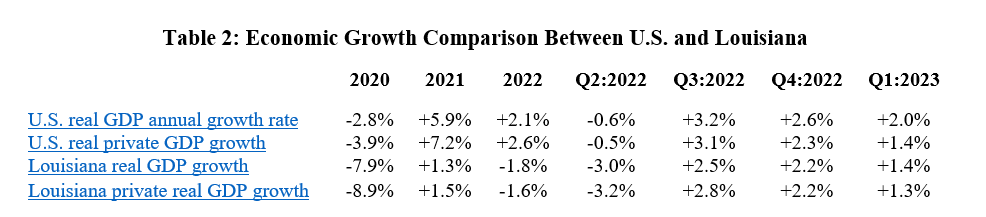

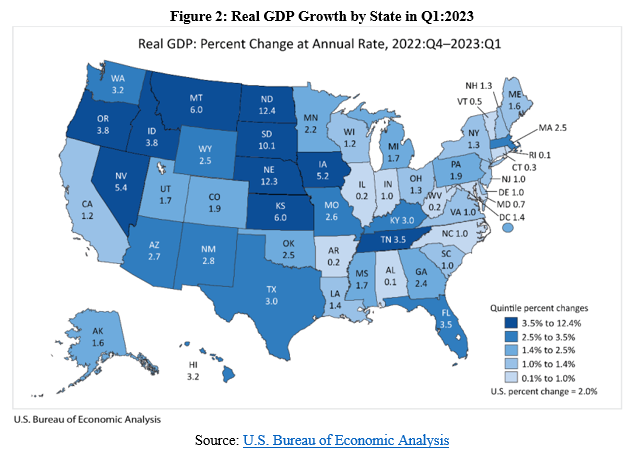

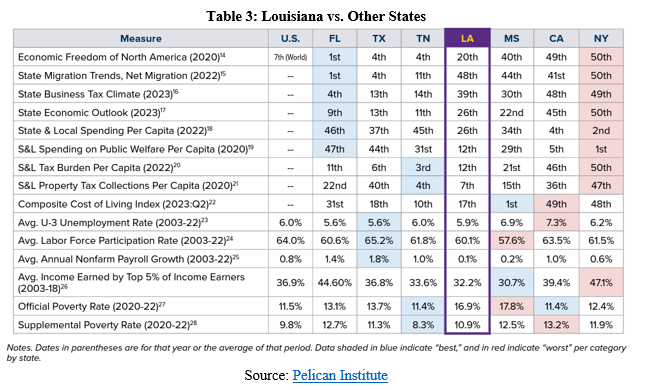

At first glance, you might think that Louisiana’s economy is doing great. After all, the state’s September 2023 jobs report shows record lows for the unemployment rate at 3.3% and and people unemployed at 67,930. Louisiana Governor John Bel Edwards cheered these data in a press release: “Louisiana continues to set records for low unemployment. We’ve had 30 consecutive months of job growth and have added nearly 280,000 jobs since the worst of the pandemic. In fact, our employment levels are now higher than they were before COVID. Experts believe that our bipartisan work to grow and diversify our economy will benefit Louisiana for years to come. Economist Dr. Loren Scott recently predicted that Louisiana will add more than 80,000 jobs over the next two years. And we’ve done it all while overcoming historic natural disasters and a state government budget crisis. I have never been more optimistic about Louisiana than I am today.” But does what you hear in the media or by some politicians match reality? Let’s dive into the data to see how things are going for Louisianans. We should know that the Pelican State has many fantastic resources but too many failed public policies that keep Louisianans from reaching their full potential. This has been the case for a while, but most recently, the jobs reports indicate slowing employment growth and a declining labor force. Work matters, as it brings about dignity and self-sufficiency and leaves fewer people needing help from government safety net programs. These data below show that while the labor market data can look good on the surface, there are many real problems facing Louisianans that need to be addressed by state leaders. Fortunately, the Pelican Institute’s “Comeback Agenda,” including our fiscal reform plan, supports ways to overcome these challenges. Here are key issues in Louisiana’s economy. Table 1 provides Louisiana’s labor market data for important dates from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. These dates are December 2007, when the Great Recession started; February 2020, when the last expansion peaked before the COVID-19-related shutdowns; April 2020, when the shutdown recession ended; and September 2023, for the latest data available. The unemployment rate would be 4.9% if Louisianans hadn’t left the state since pre-COVID. The unemployment rate is calculated using data from the household survey and isn’t a great measure of the labor market. This is because unemployment in the numerator and the labor force in the denominator are volatile measures as people enter and exit Louisiana and the labor force. Considering data from pre-COVID to compare with the Governor’s statement, the working-age population is down by 36,329 to 3.5 million. Even though the labor force is up 1,566 since then, the many people who have left the state keep the unemployment rate lower than otherwise. If we include the departed population in the labor force and unemployment, the unemployment rate would be 4.9%, substantially higher than the reported 3.3%. Moreover, if the working-age population hadn’t declined, the labor force participation rate would be 59.3% instead of the 58.9% rate today. Louisiana’s employment has not increased for 30 consecutive months. While the Governor is correct that there have been about 280,000 jobs since pre-COVID, there have not been “30 consecutive months of job growth.” The payroll survey shows that nonfarm employment is up 270,300 and the household survey shows that employment is up 295,065 since February 2020. There was an increase in nonfarm employment by 8,900 jobs in September (6th most in percentage terms of any state). But this was after cumulative losses of 3,600 jobs during June and July for an increase of just 18,100 jobs over the last four months. Over the last 30 months, there have been seven months with declining net jobs in the payroll survey and nine months with declines in the household survey, which has had four straight months of declines for a total of 17,564 fewer people employed in that period. So, Louisianans have actually been struggling over the last 30 months. Louisiana will add a projected 80,000 more jobs over the next two years, indicating slower job creation. Considering nonfarm employment over a longer period, it is up by 46,000 jobs from a year ago (20th most in the country) for a 2.4% increase (12th fastest). This would result in 92,000 jobs added over the next two years if this pace continued, but the Governor says one projection is just 80,000 jobs added over that period, indicating slower job creation. Also, nonfarm employment is down by 13,700 jobs since February 2020 (one of only a few states that have not regained lost jobs since then). Jobs in the private sector increased by 520 last month to 1.66 million, and government employment increased by 8,300 jobs to 320,500. There is growing weakness in the labor market, with some job losses and average weekly earnings not rising as fast as CPI inflation of 3.7% in many industries (Figure 1). Another weakness is economic growth. Table 2 shows how the U.S. and Louisiana economies performed since 2020, as reported by the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. The steep declines were during the shutdowns in 2020 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, which was when the labor market suffered most. Figure 2 shows how the increase in real GDP in Louisiana of +1.4% in Q1:2023 ranked 31st in the country to $289.9 billion, after an annual decline in economic output by -1.8% in 2022 which was the second worst in the country. The BEA also reported that personal income in Louisiana grew at an annualized pace of +6.2% (ranked 27th) to $258.5 billion in Q1:2023 (above +5.1% U.S. average). There was personal income growth of 0.0% in 2022, ranking 50th of the states. Compared with neighboring states based on several measures there continue to be major concerns in Louisiana (see Table 3). Bottom Line: Louisiana’s economy is weak when it comes to the labor market and economic growth and when compared with other states. Bold, transformational reforms can unleash the potential of Louisianans and make the state more competitive.

Originally published at Pelican Institute.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Vance Ginn, Ph.D.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed