|

In this Let People Prosper episode, we discuss issues related to responsible governing, like passing budgets that remain within the average taxpayer's ability to pay, local debt transparency, and criminal justice reforms where the time matches the offense. This is all essential to improving the Texas Model based on limited government that has long supported economic prosperity, as noted by today's state-level jobs report discuss.

#letpeopleprosper

0 Comments

In this Let People Prosper episode, James Quintero, Chance Weldon and I discuss the Conservative Texas Budget related to SB 500; Teacher Retirement System (TRS) of Texas related to SB 12; superintendent pay reform in HB 880; local debt issues in HB 440, HB 477, and SB 30; and a legal case regarding child safety.

#letpeopleprosper In this Let People Prosper episode, James Quintero, Dr. Derek Cohen, and I discuss key bills regarding local liberty issues related to debt transparency (HB 440 & HB 477), criminal justice reform efforts, property taxes (HB 2, HB 705, HB 648), and teacher pay/retirement (SB 3/SB 393).

#LetPeopleProsper In this Let People Prosper episode, James Quintero, Dr. Derek Cohen, and I discuss the following:

In this Let People Prosper episode, James Quintero, Derek Cohen, and I discuss key topics this week for Current Events Friday.

More to come on Monday. #LetPeopleProsper In this Let People Prosper episode 73, we discuss efforts to change Texas' rainy day fund to lower the economic stabilization fund (ESF) cap and impose a new endowment fund (SB 69), overview of an organizational meeting by the House Committee on Criminal Jurisprudence, and the latest on property tax relief that info on SB 2 in the Senate Committee on Property Tax today and the organizational meeting by House Ways & Means Committee on Wednesday.

#letpeopleprosper It's Current Events Friday!

In this Let People Prosper episode 72, James Quintero, Dr. Derek Cohen, and I discuss this week's current events. The big stories this week are Governor Abbott's State of the State, President Trump's State of the Union, and property tax hearing held by the Texas Senate Committee on Property Taxes. We dive into each of these issues to consider which government actions preserve liberty and which ones don't. Regarding property taxes, there's some hope in sight! Senate Bill 2 could provide historic property tax reform (read my written testimony and watch testimony at time 1:13:10) that would put in place a 2.5% property tax revenue rate that would trigger an automatic election in November for a local government that wanted to increase their revenue above that point. This reform is an essential element for any property tax relief of lowering property tax bills like TPPF’s plan to eliminate the school M&O property tax over time by slowing spending growth. #letpeopleprosper In this Let People Prosper episode 71, I chat with James Quintero and Dr. Derek Cohen of TPPF about the benefits of bail reform (SB 628 & SJR 37), the costs and benefits of the latest version of reforming the Teacher Retirement System of Texas (SB 393) (more on TRS problems here), and what to expect in Gov. Abbott's State of the State (like a possible emergency item of property tax reform).

#letpeopleprosper In this Let People Prosper episode 70, I chat with James Quintero and Dr. Derek Cohen about the recently released bills that would both provide property tax reform with the same language (Senate Bill 2 & House Bill 2). Read TPPF's press release here.

The press conference attended by Governor Greg Abbott, Lt. Governor Dan Patrick, Speaker Dennis Bonnen, Chairman Paul Bettencourt, and Chairman Dustin Burrows shows the unity of this particular measure. These bills would provide property tax reforms to increase transparency, change up the appraisal system, and impose a revenue trigger of an automatic rollback election: (1) if revenue is set to grow by more than 8% for local tax jurisdictions with less than $15 million in total revenue from sales and property taxes, and (2) if revenue is set to grow by more than 2.5% for all other taxing entities. This is a step in the right direction to slowing the growth of skyrocketing property taxes and we look forward to working with leadership and legislators to lower tax bills by limiting state spending as well. We also discuss the benefits of SB 523, which would restructure occupational licenses for those with particular criminal records. #letpeopleprosper In this Let People Prosper episode 68, I interview James Quintero, Director of the Think Local Liberty project at the Texas Public Policy Foundation, about reining in skyrocketing local property taxes, increasing local debt transparency, and highlighting frivolous local spending. High taxes and debt are always and everywhere a spending problem. James makes that point clear in this episode. Don't miss it!

#letpeopleprosper Perhaps no issue unites Texans across the state like the need to reduce property taxes. But any property tax reform will have consequences that affect how we fund education, pay for roads, grow our economy, improve access to health care, and more. Experts and policymakers take on this critical question and look for solutions in the 86th Legislature.

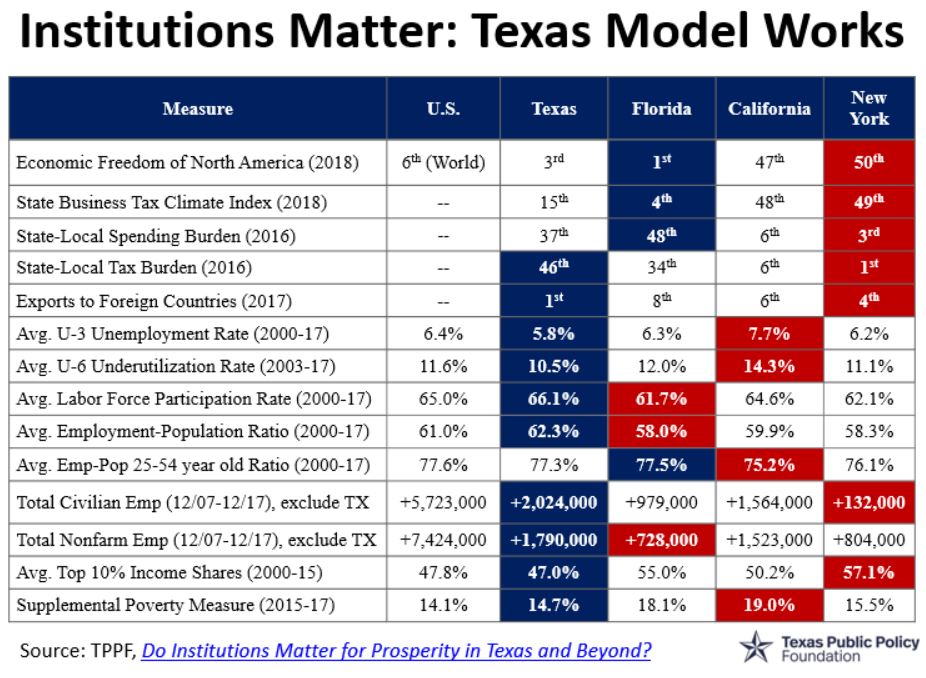

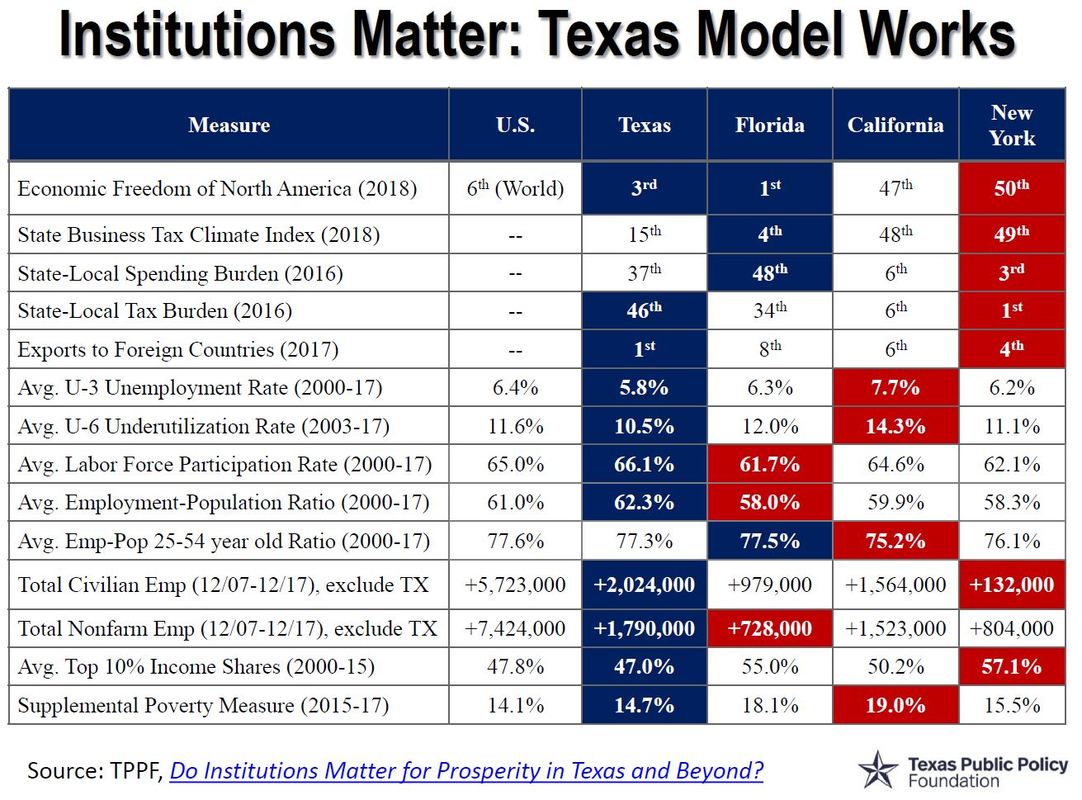

Great discussion with Dr. John Diamond from Rice University's Baker Institute, Senator Paul Bettencourt, Judge Glenn Whitley, and Representative Drew Springer. Read more about TPPF's plan to cut property taxes and find out how much you would save under this plan over time here. In this Let People Prosper episode 67, let's discuss the importance of sustaining and improving the Texas Model of no personal income tax, relatively low taxes, relatively less government spending, and sensible regulation that allow entrepreneurs opportunities not available elsewhere. This can be boiled down to: Institutions Matter. Let's recall previous discussions highlighting these key points while noting how Texas led the way in job creation again in 2018.

#LetPeopleProsper Week 2 TXLege Happenings--Ban Income Tax, Cut Property Tax, & Free Trade: Let People Prosper EP 661/18/2019 In this #LetPeopleProsper episode 66, let's discuss what happened during Week 2 of the 86th Texas Legislature.

My op-ed on the need to ban a personal income tax in Texas in the Victoria Advocate was tweeted by Governor Greg Abbott. That op-ed also noted the need to cut the school maintenance and operations property tax with TPPF's plan of simply slowing government spending growth. And I had another piece in The Hill that noted the benefits of free trade. Finally, the Legislative Budget Board adopted a spending limit based on population growth and inflation last Friday. Near the end of the discussion (watch starting at 6:20), Chair Jane Nelson notes, at Speaker Dennis Bonnen’s request, that The Honorable Talmadge Heflin said TPPF wouldn’t include Harvey-related money in budget figures. This is correct as long as it is transparent and one-time funding. It's a pleasure to work with him every day. Regarding the recent budgets, we posted a blog post with more information comparing the House and Senate budget recommendations with the Conservative Texas Budget. #letpeopleprosper TPPF's Policy Orientation Recap & Texas' LBB Spending Limit: Let People Prosper Episode 641/13/2019 In this Let People Prosper episode 64, let's discuss the Texas Public Policy Foundation's Policy Orientation, which was a sold out event that helps define the narrative for the 86th Texas Legislature, and highlight the recent spending limit set by the Legislative Budget Board.

The following are the panels that I moderated or participated in some capacity and my key takeaways with resources:

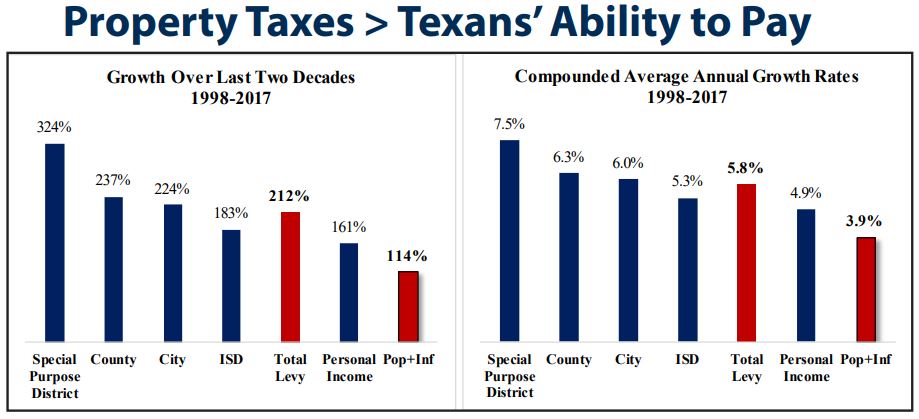

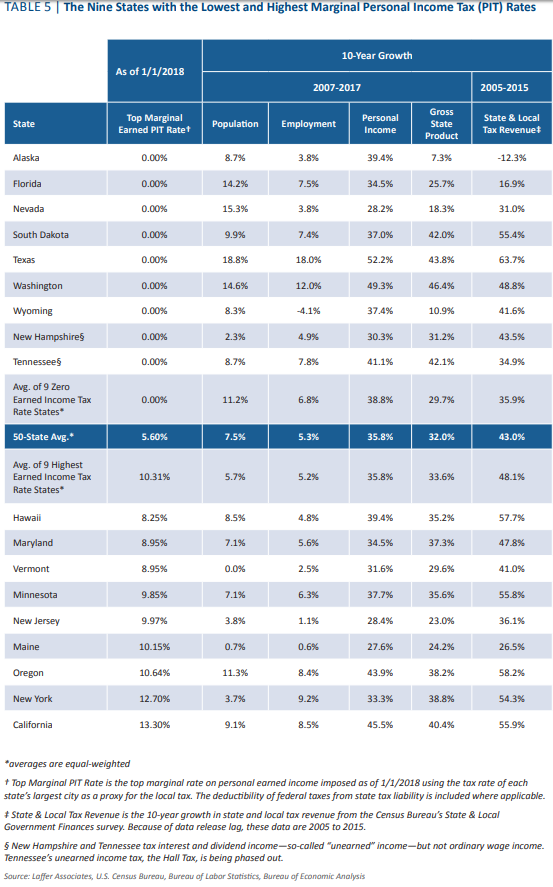

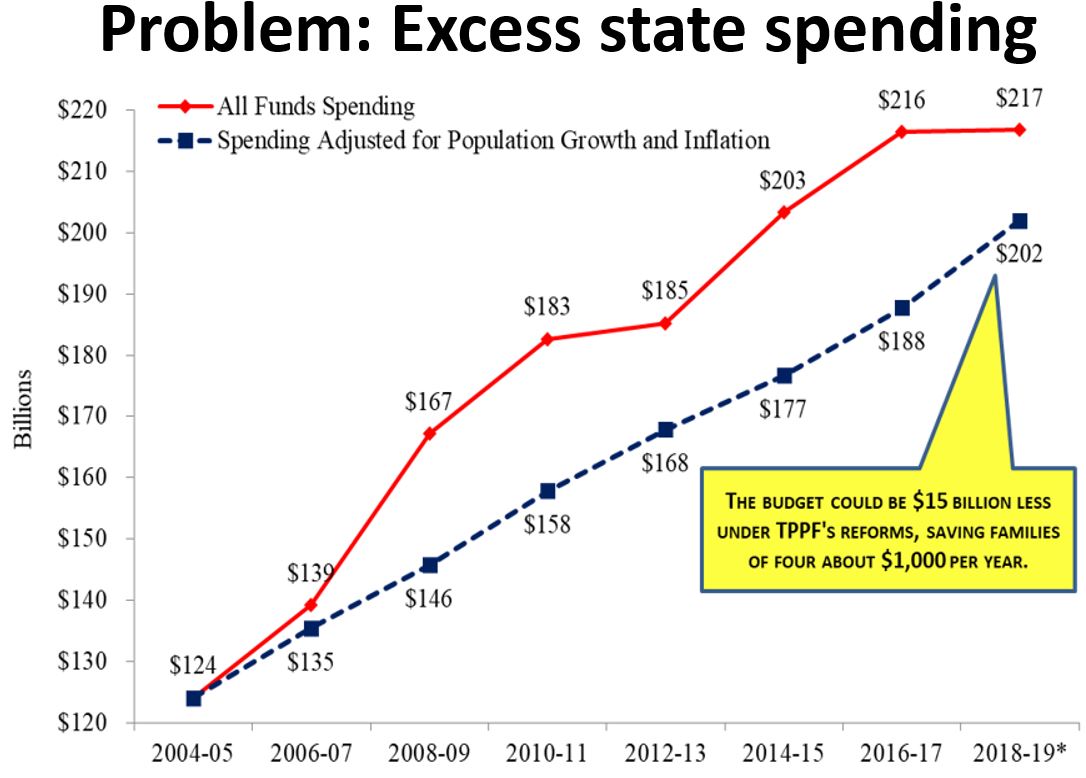

The other big news on Friday was that the Legislative Budget Board (LBB) set the state's spending limit for the upcoming 2020-21 budget. This spending limit is on only general revenue not dedicated by the constitution which is less than half of the total budget. While statutorily the spending limit should be based on growth in personal income, last session the LBB chose the rate based on population growth and inflation. This time the spending limit is 9.89% for the 2020-21 budget, which is based on an increase of 8.39% in population growth and inflation and 1.5% for Harvey. This is another good sign that the LBB continues to use a measure for the limit that better matches the average taxpayer's ability to pay than the inappropriate growth rate of personal income. This spending limit is in-line with the recent BRE increase of 8.1% in general revenue-related funds and provides funds available to cover needed expenses along with property tax relief. Specifically, the Legislature could use half of the funds of about $4.4 billion for spending and 90% of the rest of the funds of about $4.1 billion to buydown the school maintenance and operations property tax. Despite the economic success of the Texas Model of fiscally conservative governance, a skyrocketing local property tax burden remains one of the state’s most pressing policy challenges. Property taxes have been growing faster than Texan’s ability to pay for them, increasing the need to eliminate them. You get less of whatever you tax. This key economic insight suggests the best type of taxation does the least economic harm, achieved by limiting government spending to only securing liberty. The evidence is clear that Texas should never have a personal income tax. There is nearly a consensus that is true, but there is a growing consensus that Texas should eliminate property taxes that keep Texans renters forever. Property taxes are an inefficient type of tax. They are based on primarily subjective valuations by appraisal review boards and determined tax rates by local tax entities with little to no feedback from citizens. Given the rising property tax burden and its inefficient collection mechanism, they should be eliminated in exchange for a more efficient, slower-growing sales tax based on objective market transactions that would help appropriately remove taxes on capital (i.e. property)—the driver of the wealth of states. Property taxes are more regressive than a sales tax. Opponents of a sales tax say it is too regressive, whereby people with lower incomes people pay a larger share of their income to taxes than those with higher incomes. The Texas Comptroller’s recent report confirms that both sales taxes and property taxes are regressive, according to the “suits index” (see following two tables), but suggests property taxes are less regressive. However, this analysis (and others like it) do not account for the fact that sales taxes are paid once at purchase yet property taxes are paid annually, hurting low- and fixed-income Texans the most because the costs compound over time. A property tax also keeps people from getting their first home and kicks many people out of their home and business. Appropriately accounting for these cumulative costs indicates a property tax is more regressive. Texas should ultimately have only a single-legged barstool in the form of a broad-based sales tax. Some talk about the need for a three-legged stool of taxation. These legs include a sales tax, property tax, and a personal income tax. Because Texas appropriately doesn’t have the latter, the argument is that there is a need for the other two. But that’s incorrect. Texas needs the most efficient tax system possible to fund limited government. That’s done by expanding the sales tax base as wide as possible to not pick winners and losers to keep the rate as low as possible. There are paths to swapping out city and county property taxes with a higher local sales tax rate if the state doesn’t broaden the base. This is also a good option as it provides a direct funding source for local governments’ maintenance and operations if, and only if, they eliminate the property tax with a revenue neutral swap. Ideally, the sales tax rate would not be allowed to ratchet up further after the swap and the property tax could never come back. The school district maintenance and operations property tax, which comprises about 45 percent of the total property tax burden in Texas, could also be swapped out with a sales tax. A broader sales tax base could allow the rate to fall. Here is an overview of possible rates and sales tax bases to eliminate the school district M&O property tax in Texas with 2017 data, which the ideal option would be to expand the base and not tax property, as property is capital that supports economic prosperity. Texas should limit spending to limit taxes. While sales tax collections can be more volatile than property tax collections from economic changes, sales taxes better reflects taxpayers’ ability to pay than a property tax that they have little control over. Also, property taxes often don’t reflect the economic climate but rather the whims of appraisal districts and local officials that hurt property holders in the process when their incomes are falling. More importantly though, Texas governments must practice spending restraint so that excessive spending doesn’t drive taxes higher than taxpayers’ ability to pay. High taxes are always and everywhere a spending problem. This is why there is need to limit spending growth to no more than population growth and inflation, two key measures that reflect the ability to pay from more people and wage growth that’s highly correlated with inflation. By practicing spending restraint, excess taxpayer dollars can be used to lower the sales tax rate after a swap or could even be used to cut the school M&O property tax in the meantime until the elimination of school districts’ maintenance and operations property taxes.

By practicing fiscal restraint and eliminating all taxes in Texas except for a broad-based sales tax, the Texas Model would support even greater prosperity for all Texans. In this Let People Prosper episode 58, let's discuss education-related issues in Texas of school finance reform, property tax relief, and the Teacher Retirement System (TRS) of Texas pension solvency.

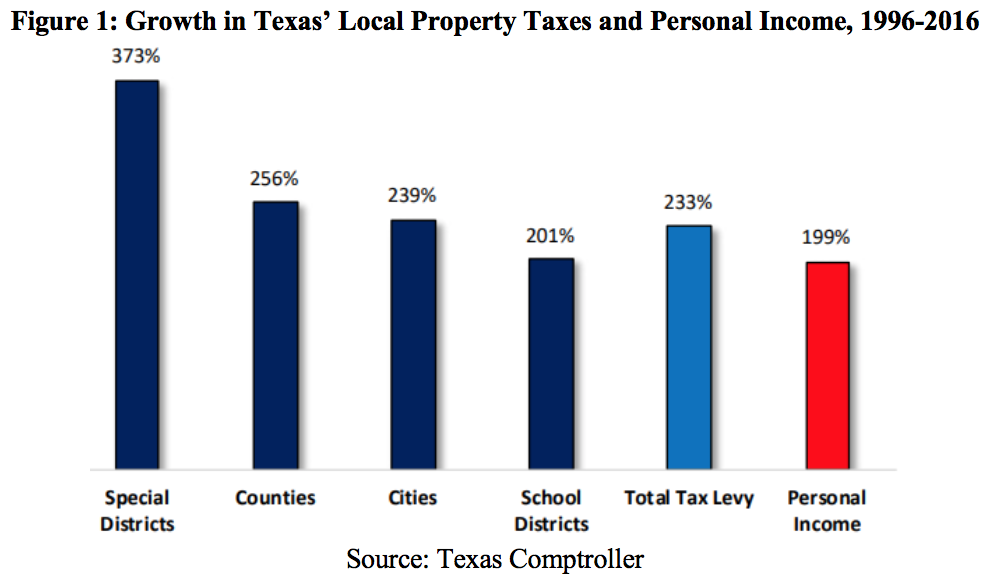

To sum up, taxpayers have increased funding for public schools for years (see here and here) and now it's time for those elevated current dollars to be spent wisely to the classroom for improved education outcomes. School finance also includes property tax relief which should be accomplished by following the TPPF plan of actually lowering property taxes. And the latest TPPF-Reason Foundation paper highlights the mounting problems with the TRS pension that must be addressed soon before the pocketbooks of teachers and all taxpayers are hit. There's much on the line for education in Texas. Serious discussion about spending taxpayer dollars wisely, lowering property taxes, and assuring the TRS pension system is solvent through reform are essential elements of improving education in the Lone Star State. #LetPeopleProsper In this Let People Prosper episode, let's discuss one of the things that's on most Texans' mind: property taxes. I recently testified before the Texas Commission on Public School Finance's Revenue Workgroup on the problem and solutions to wretched property taxes in Texas. Here's my written testimony and you can watch my oral testimony at time 59:45 here. Texas’ property tax system has turned property owners into renters, where government is their landlord and Texans who struggle to pay annual tax bills face confiscation of their properties. Additionally, the growth of government is harming taxpayers and the economy through higher taxes and more regulation. The goal must be to eliminate all property taxes as they violate property rights, destroy economic growth, and disproportionately hurt the poor while being subjectively determined as they support excessive local government spending. A good place to start down that road is by ending nearly half of the property tax burden in Texas through the elimination of the school maintenance and operations (M&O) property tax, which is supported by the 18 groups in the Conservative Texas Budget Coalition. This is relatively easier than other local tax jurisdiction because the state already determines the school finance formulas and has a way to distribute funds to school districts. Let's discuss. First, we must identify the problem. From 1996 to 2016, total property taxes across the state have increased by 233% while the school portion of the property tax increased by 201%. Personal income has increased by 199%; however, the best metric of the average Texan's ability to pay taxes is measured by the compounded growth of population plus inflation for that period, which was only 123%. This means that the total tax levy increased by 1.9 times more than pop+inf and the school district tax levy increased by 1.6 times more than the average Texan's ability to pay. It's no wonder that many people are being forced out of their homes and businesses because of skyrocketing property taxes. This is a travesty what government is doing to people who are trying to leave a legacy for their kids and grandkids. This points to the disease of the symptom of high taxes: excessive government spending. Taxes (and deficits) are always and everywhere a spending problem. To gain control of skyrocketing taxes, we must first get control of the driver of the problem in excessive government spending. This brings us to a solution: By limiting state and local government spending, Texas can use taxpayer dollars collected at the state level to eliminate the school maintenance and operations (M&O) property tax, which is nearly half of the property tax burden, very soon. While other options have been tried in the past, like raising the homestead exemption and swapping the property tax with a reformed franchise tax ("margins tax"), those didn't permanently reduce property taxes--making those attempts a failure in the eyes of most taxpayers. Fortunately, there are solutions. One option is to permanently buy down the school M&O property tax with state surplus dollars until it is eliminated. Here's how:

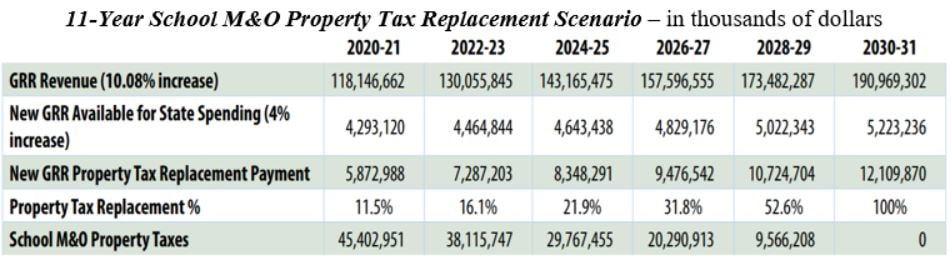

Another option is to replace the school M&O property tax by broadening the sales tax base and limiting state and local government spending. Here's how that could work:

Clearly there is no silver bullet. This will be a difficult hill to climb whichever option is chosen.

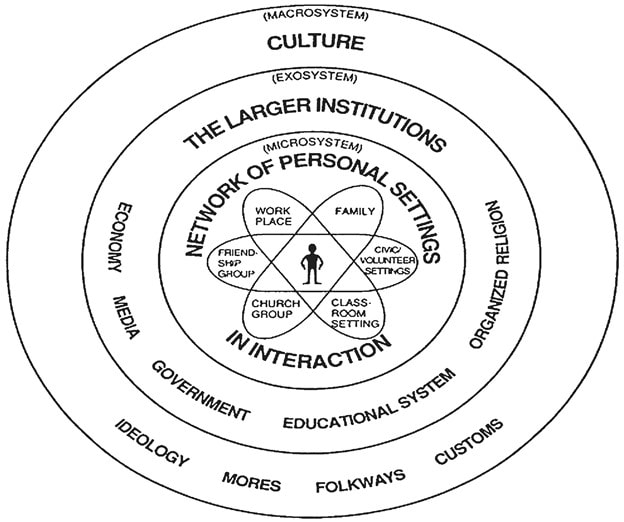

Recently, two economists from Rice University estimated that if the buy down option or the swap option over time was chosen, the Texas economy could expand by about $12.5 billion above expected growth and private sector job creation could increase by 183,000 net jobs above expected growth soon after reform. The Texas Model is strong, but there's more that must be done. These options would provide a clear path to more prosperity and less of a burden of holding property until you can finally own it when property taxes are eliminated entirely. In this Let People Prosper episode, let's discuss how the recent election gives us insight on how we need more civil discourse to find ways to strengthen institutions so people can flourish. My recent paper on how institutions matter provides a good overview of what I discuss in this episode along with economic data to support the theory. Here is a graphic that explains rather well the ecology of human development. The data provide overwhelming evidence that the Texas Model of inclusive institutions with a relatively low tax-and-spend burden, no individual income tax, and sensible regulation provides an institutional framework supporting more job growth, higher wages, lower income inequality, and less poverty than in comparable states and the U.S., in most cases. Texas is doing something right. Other states and D.C. would be wise to consider adopting Texas’ inclusive economic and political institutions that champion individual liberty, free enterprise, and personal responsibility. This is a path to providing an economic environment that allows entrepreneurs the greatest opportunity to thrive and for prosperity to be generated for the greatest number of people. Despite this success, improvements are needed to keep the Texas Model competitive and create even more opportunities for all to flourish. These improvements to Texas’ institutional framework include:

• limiting the growth in government spending, • eliminating the state’s onerous business franchise tax, • reducing barriers to international trade, • reducing the escalating burden of property taxes, and • relieving Texans from burdensome occupational licenses. Even with these improvements, the data overwhelmingly show it was not a miracle in Texas, but rather abundant prosperity generated by Texans from a proven institutional framework called the Texas Model. By strengthening institutions to let people prosper, we can also engage in more civil discourse so that we have many opportunities to work together. Texans appreciate living in a state that values liberty, sensible business policy, and, perhaps most importantly, a strong dislike for taxes, which inevitably infringe on the first two values.

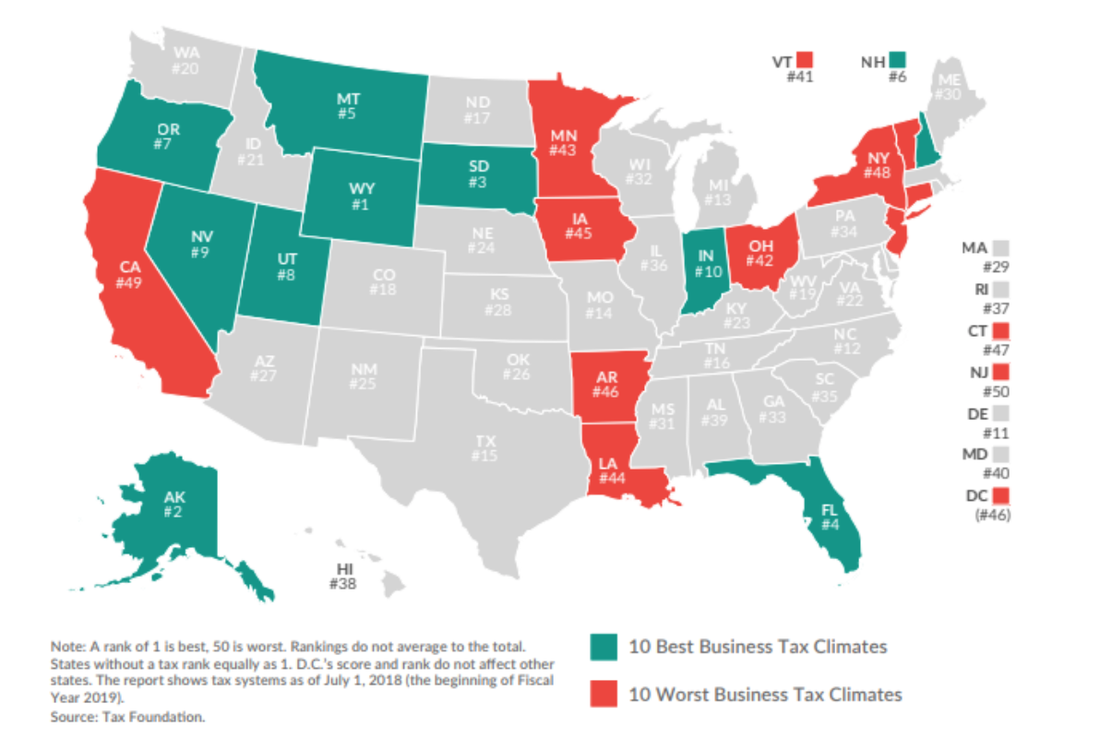

But, in comparison with other states, Texas is beginning to lose its competitive edge in business climate as noted in the Tax Foundation’s recently released 2019 State Business Tax Climate Index. The report ranks all fifty states based on the burdens of each state’s corporate income tax, individual income tax, sales tax, unemployment insurance, and property tax. Figure 1 presents the ranking of each state whereby the top-ranked states include either states without at least one major tax, such as the individual income tax, or states that have all major taxes with low rates and broad bases. Meanwhile, poorly ranked states share similar shortcomings such as complex non-neutral taxes and comparatively high tax rates, such as in the three worst ranked states: California (48th), New York (49th), and New Jersey (50th). In this year’s report, Texas’ overall rank took a hit, sliding from 13th best nationwide in 2018 to 15th best for 2019. Yet, the drop is not due to new policy as the state’s individual category scores remained unchanged and actually improved by 8 ranks for Unemployment Insurance. Rather, the new lower overall rank highlights Texas’ stagnation in decreasing its tax burden as other states jump on the opportunity to increase their prosperity from lower burdens. While Texas excels in the category of individual income tax because as it doesn’t have one, the state is consistently held back by its corporate income tax portion of the index, which remains unchanged at 49th, or second worst! This is because Texas’ business tax is a gross receipts-style tax that is costly to comply with and pay. If Texas eliminated this onerous tax, the Tax Foundation has found the state’s business tax climate overall rank could improve to 3rd best. And the Texas Public Policy Foundation and the Legislative Budget Board (LBB) have estimated large economic gains. Texans have been hurt by burdensome local property taxes for too long, with that ranking in the report being 14th worst in the last three years. We know all too well about complexity, high rates, and lack of voter oversight of Texas’ local property tax system. To overcome this over-burdensome system, the Foundation has recently released a report detailing a strategy to slow the growth of state and local government spending in order to use surplus state funds to permanently reduce the school maintenance and operations (M&O) property tax until its eliminated. This would end nearly half of the property tax burden in Texas within about a decade while increasing funding for school districts over time with state taxes that would eventually fund 100 percent of schools M&O. Moving forward, Texas’ elected officials should consider these rankings by the Tax Foundation and other reports when looking for ways to improve the state’s business tax climate so Texans have the best chance to start a new business or gain employment. The Texas model of limited government has contributed to human flourishing, where 24 percent of new civilian jobs created nationwide have been since December 2007, but there’s always room for improvement. https://www.texaspolicy.com/blog/detail/texas-business-tax-climate-needs-improving Texas’ property tax system has turned property holders into renters, where government is their landlord and Texans who struggle to pay annual tax bills face confiscation of their properties. Additionally, the growth of government is harming taxpayers and the economy through higher taxes and more regulation.

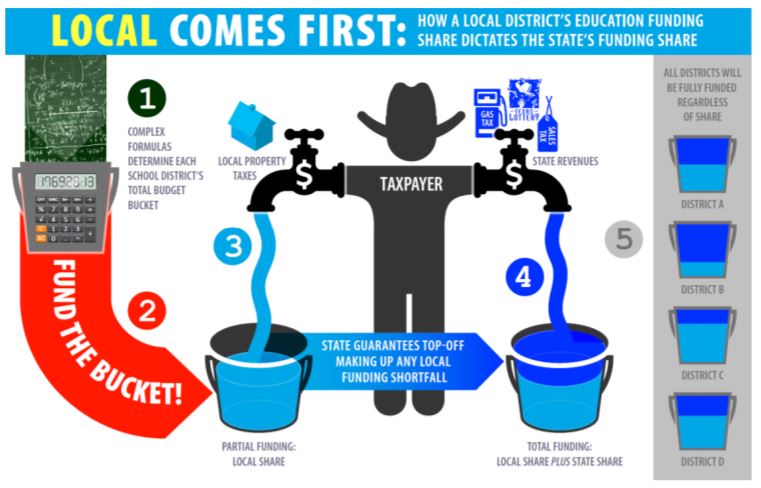

For example, Eddie Wilson owns the landmark Austin restaurant Threadgill’sbut recently announced he must close a location soon noting that he is “Flummoxed and bludgeoned by property tax increases, the grim truth is that we can’t afford it on the slim margins you make on meatloaf and chicken-fried steak.” Substantial, permanent property tax relief is needed. The Foundation’s recent report provides a plan of limiting government spending to eventually abolish property taxes in Texas by starting with eliminating the school maintenance and operations (M&O) property tax—nearly half of the property tax burden in Texas. The school M&O property tax is a good place to start because the level of student funding is determined by state funding formulas that are first funded by local property taxes and then by state dollars. Although there’s a lot of noise about whether local governments or the state legislature is at fault for a skyrocketing local property tax burden, the truth is excessive spending is the problem and taxpayers foot the bill regardless (see figure below). The relative ease of this process is lost with other local tax jurisdictions. Our plan is simple: State and local governments would limit spending such that state revenue permanently replaces the school M&O property tax within about 11 years. In other words, every dollar not spent by the state or school districts will produce a 90-cent property tax cut for Texans until half of the property tax in Texas is eliminated. Here are the plan’s details:

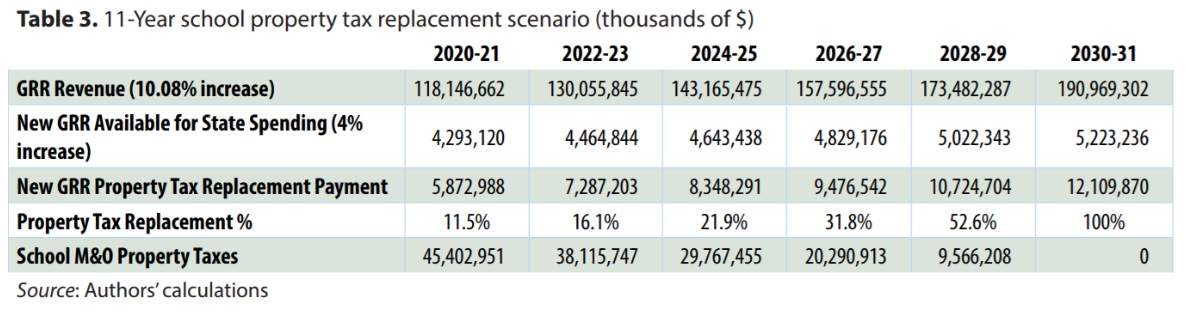

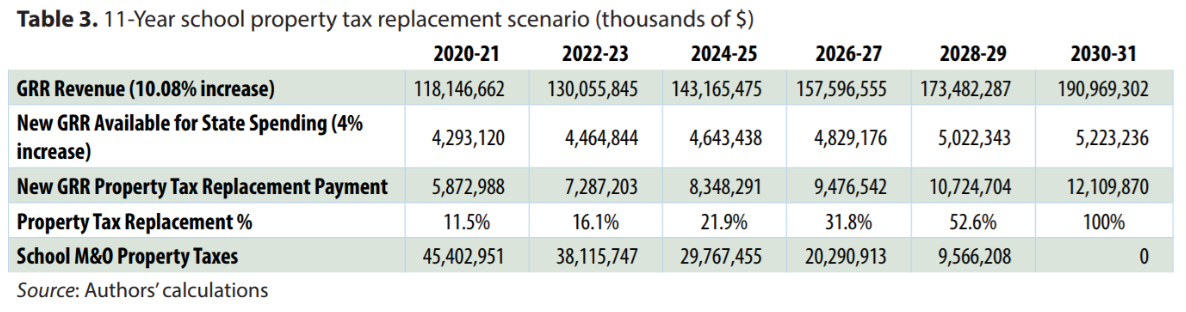

Table 3 shows how the plan could work mathematically given the above criteria: Under this plan, Texans will experience substantially lower property tax bills immediately and slower growth in them over time along with the broader economic benefits of slower government spending and a lower tax burden. Other options, such as sufficiently broadening the sales tax base, that begin with spending restraint to replace the school M&O property tax may be considered to deal with this problem. Limiting government spending and using state dollars to replace nearly half of the property tax burden that funds education would shift Texas toward a more efficient sales tax system to let people prosper. https://www.texaspolicy.com/blog/detail/property-tax-relief-in-texas-plan-to-eliminate-school-mo-property-tax We previously discussed the problems with Texas’ skyrocketing property tax burden. Let’s now consider past failed property tax relief attempts signaling a need for options that will provide permanent relief.

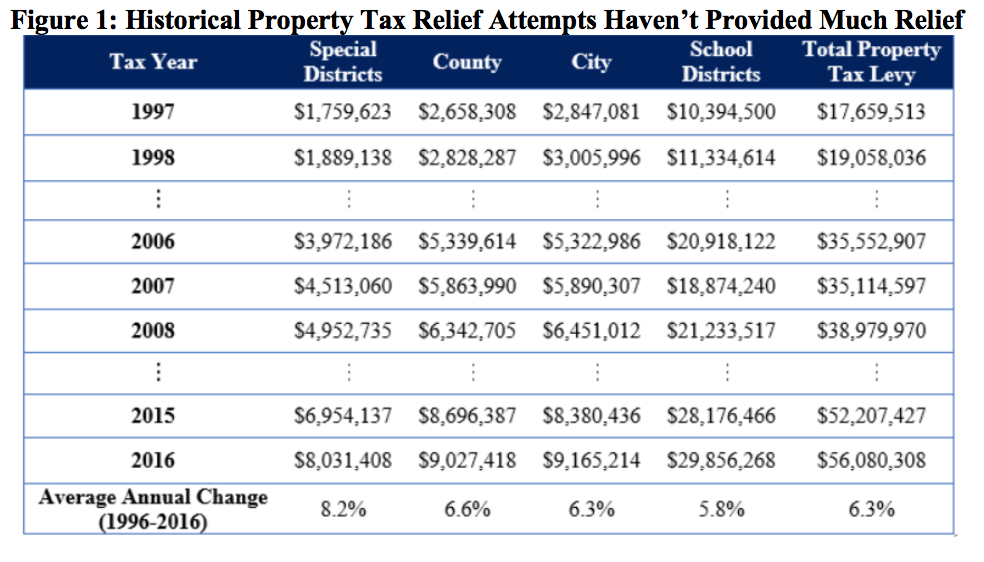

Since Texas’ modern property tax system took shape in 1979 with the passage of the “Peveto bill,” there have been three major attempts by the Texas Legislature to provide relief for taxpayers. Unfortunately, none of the attempted solutions created lasting reductions in property taxes as the attempts failed to address increased spending—the cause of increasing taxes—and instead simply shifted around the burden. 1997 Reform Attempt: Homestead Exemption Increase by $10,000 The 75th Texas Legislature attempted to reduce the rising property tax in 1997 by increasing the homestead exemption for school district property taxes by $10,000. Instead of allowing only $5,000 to be deducted from the taxable value of an individual’s property, the taxpayer could now deduct up to $15,000. The increased exemption was accompanied with homeowners who were 65 and over receiving a freeze on their school district property taxes. The total tax relief package was estimated at $1 billion. However, it resulted in little to no effect as school district property taxes increased by nearly $1 billion and total property taxes increased $1.4 billion the year after implementation and continued rising thereafter. 2006 Reform Attempt: Property Tax-Franchise Tax Swap After the Texas Supreme Court determined the school finance system was unconstitutional in 2005 from an essentially statewide property tax, the Legislature in a 2006 special session aimed to bring property tax relief. The solution was a reformed business franchise tax to what’s known as the margins tax today and increase the motor vehicle sales tax and tobacco tax while also changing the school finance formulas. While the outcome was an initial reduction in school district and total property taxes, the declines were marginal the first year with taxes being substantially higher than 2006 in 2008. As a result, instead of sustained property tax reduction, Texans experienced an increase in both local property taxes and state taxes. Moreover, the swap exchanged an already poor property tax system with an arguably worse margins tax that should be eliminated. 2015 Reform Attempt: Homestead Exemption Increase by $10,000 Similar to the 1997 reform, the 84th Texas Legislature looked to raise the homestead exemption for school districts property taxes another $10,000 to $25,000. Again, lower local property tax collections were replaced with state funds so as to not decrease school district budgets. Yet, much like 1997, there was no improvement in the tax burden as school property taxes increased by $1.7 billion and all property taxes increased by almost $4 billion the next year. Conclusion With past property tax relief failures of increasing the homestead exemption and the franchise tax swap, the time has come for a strategy that employs reducing the growth of government spending at the state and local levels while using state dollars to eliminate property taxes. Despite the economic success of the Texas Model of relatively fiscally conservative governance, a skyrocketing local property tax burden remains one of the state’s most pressing policy challenges.

While Texans have the luxury of not paying a state personal income tax, which should be constitutionally banned, they’re currently weighed down by more than 5,100 local taxing jurisdictions that boast the sixth highestproperty tax rate nationwide. These locally-determined tax rates along with often subjectively appraised property values combine to give the total property tax levy statewide of $56 billion in 2016—contributing to an average property tax burden of more than $8,000 per year for families of four. Although many Texans live in uncertainty year-to-year on what their property tax bill will be, much of the damage of such ominous tax burdens are not so uncertain: discouraged economic growth, distorted investment decisions, depressed job creation, and ultimately renting property from the government forever. While the pain is felt statewide, it’s particularly felt among housing-rich but income-poor individuals, such as the elderly, who often must move as increasing tax liabilities extend beyond their means. In fact, some Texans who have paid off their mortgage now pay more for their property tax liability than prior mortgage payments, forcing them out of their home. The high property tax burden also keeps some people from ever having the means with which to purchase property. Both of these issues limit the liberty and economic prosperity of Texans from property taxes at often no fault of their own. This is particularly harmful because people aren’t able to ever own their home but rather pay rent to the government forever. And even those who do not have property are burdened as renters can reasonably expect property managers to pass the tax along to them and consumers pay more goods and services as business owners do the same. The culmination of these increases by local tax jurisdictions contribute to the total property tax levy statewide increasing by 233 percent to $56 billion in property taxes collected in 2016—the single largest tax imposed in the Lone Star State. For comparison, there may be a need for increasing spending and therefore taxes to fund increases in population and inflation. However, in this period, the state’s population growth increased by 47 percent and price inflation increased by 53 percent—collectively well below the increase in property taxes. On an average annual basis, the total property tax levy increased by 6.3 percent during that period; however, population growth increased by 1.9 percent and price inflation increased by 2.2 percent. Again, these growth rates indicate the mounting burden on Texans compared with a potentially reasonable argument for spending and taxing more. With many local tax jurisdictions raising property taxes at rates that are outpacing key measures of Texans’ ability to pay, the Texas Legislature has attempted to limit the growth of property taxes but to little avail. The steady increase in the property tax burden despite these unsuccessful attempts signal the real issue: Texas’ local governments don’t have a revenue problem, they have a spending problem. By first identifying this spending problem, we can begin to discuss real property tax relief. In this Let People Prosper episode, I discuss how property taxes continue to skyrocket in Texas and highlight options that would provide property tax relief. The key to any long-term tax relief is to limit government spending so that the burden of government can be reduced.

The result of taxing something is that you will get less of it. That's simple, correct? But the details of how to best collect taxpayer dollars to fund limited roles for government gets complicated. I try to break this down simply at the video above. According to the Texas Comptroller, property taxes and sales taxes are both regressive. Any time you have a flat tax rate, higher income people will pay a lower share of their income on taxes than lower income people. But the costs of property taxes are substantial, with businesses and individuals each paying about half for school M&O property taxes. Sales taxes, on the other hand, allow people the freedom to decide how to spend their money, don not have to tax real estate (capital formation and accumulation--keys to wealth of nations), and are transparent. Individuals pay about 60% of sales taxes collected while businesses submit about 40%, but we know that businesses don't ultimately pay taxes because they just pass those costs along to consumers (us) in the form of higher prices, lower wages, and fewer jobs available over time. As noted in previous episodes, I have long supported the elimination of property taxes in Texas. There are multiple ways to do so by possibly swapping them (sales tax rates are lower now because of expanded economic growth since these rates were calculated) with a reformed sales tax and/or buying them down permanently over time. The key is to limit government spending so that the burden of government can be reduced. We know that sin taxes (e.g. carbon tax or cigarette tax) or tariffs are poor forms of taxation. Income taxes are also a terrible form of taxation. Check out the table below that provides information for the 9 states without a personal income tax and the 9 states with the highest personal income tax rates. Those states without a personal income tax blow the others out of the water regarding multiple economic indicators. Of course, the key is limiting spending. Let's move to a tax system with just a sales tax for more economic prosperity, which eliminating the school M&O property tax would be a great start. I gave the following presentation at a policy forum on property tax reform at the Arlington Chamber of Commerce. Here's an overview of the forum from the Greater Arlington Chamber of Commerce: Property tax relief and slowing the growth of property taxes proved to be a topic capable of bringing approximately 120 business leaders and elected officials together at the Greater Arlington Chamber of Commerce on Friday, August 3. Four experts on property taxes presented their perspective on the issues and then responded to questions from Tarrant County Property Tax Assessor/Collector Ron Wright. The event was the first ever sponsored by the Coalition of East Tarrant Chambers. Vance Ginn, Chief Economist with the Texas Public Policy Foundation in Austin, presented TPPF's view of how to completely eliminate school maintenance and operations property tax. Dr. Aaron Reich, President of the Arlington ISD Board of Trustees, talked about the complications of the Texas system for funding property taxes and how it seems to short change districts like Arlington. He made the point the state uses taxes collected as "school" taxes for other state expenses like health care and transportation. County Judge Glen Whitley represented the perspective of cities and counties and made the point that without a state income tax, which he does not favor, Texas has a two-legged stool which is hard to sit on. He took great exception to the idea of eliminating property taxes and replacing them with more sales tax could be made to work. State Representative Matt Krause brought the perspective of the legislature to the discussion. He shared about the state's overall shortage of funds and how growing Medicaid expenses are crowding other important items in the budget. Follow this link to read a summary of the presentations. Click here to view the video of the entire Forum.

In this episode (YouTube channel Vance Ginn Economics), I explain how institutions matter from an economic, social, and political perspective. This episode is longer than usual (30 minutes) to go through these institutions and explain how the Texas Model supports prosperity while highlighting how it could be improved by limiting spending and eliminating property taxes--starting with school property taxes. Given how federal institutions have failed for so long, though they are improving now, there is a need to look at the states. A good comparison is the largest four states in terms of economic output and population of California, Texas, New York, and Florida. These states have very different institutions, whereby Texas and Florida have primarily inclusive (liberty-related) institutions and California and New York have primarily extractive (redistributionary) institutions. The economic results from these are clear over the last decade-plus with Texas and Florida leading the way in most economic indicators, even when considering income inequality and poverty. I highlight how the Texas Model has led the way in terms of prosperity, but there is more that needs to be done, specifically limiting state and local government spending. Specifically, there is no education spending problem in Texas, as noted by data from the Texas Education Agency, and the state share of education spending hasn't declined. So, the state spending more, as education lobbyists request, will not lower property taxes. I then go through the option of eliminating school maintenance & operations property taxes over 11 years by limiting spending and using state surplus dollars to permanently buy school property taxes down until they are eliminated. As often asked at these events, I also briefly discuss the option of swapping school property taxes with a sales tax that has a broader base so the rate doesn't increase much if at all then cut taxes with surpluses dollars thereafter. I discuss other ways to improve the Texas Model as well, such as passing a stronger state spending limit and eliminating the business margins tax. These steps will allow Texas to be even more prosperous by getting government out of the way with an institutional framework that support entrepreneurial activity and human flourishing today and far into the future. Thank you for watching! Please share as you see fit. Have a prosperous day!

|

Vance Ginn, Ph.D.

|

||||||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed